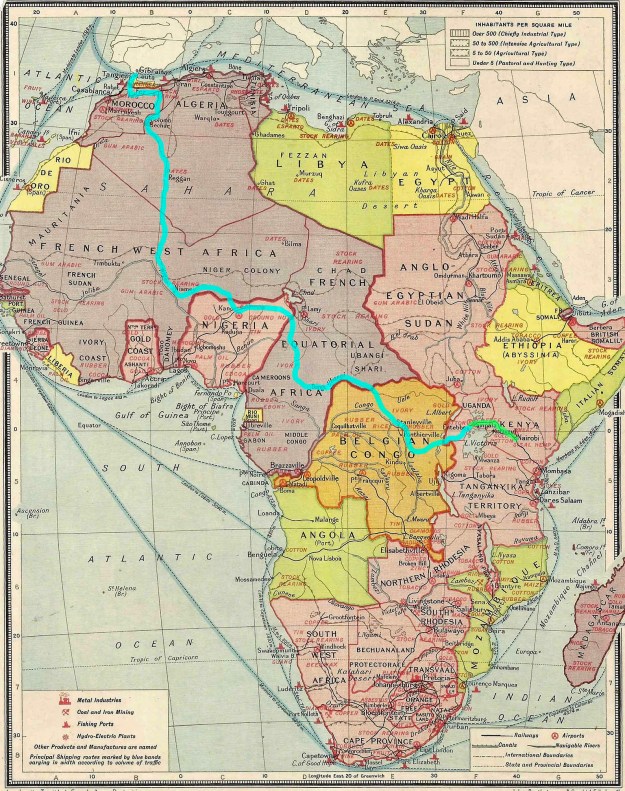

Curious about the Royal Enfield Himalayan 450, Desert Rider Jon and I rented a couple for eight days in the High Atlas. The bikes proved to be a bit of a disappointed (my review), but I was reminded what makes southern Morocco special: the hills and mountains, not the over-rated desert which many visitors seek to experience.

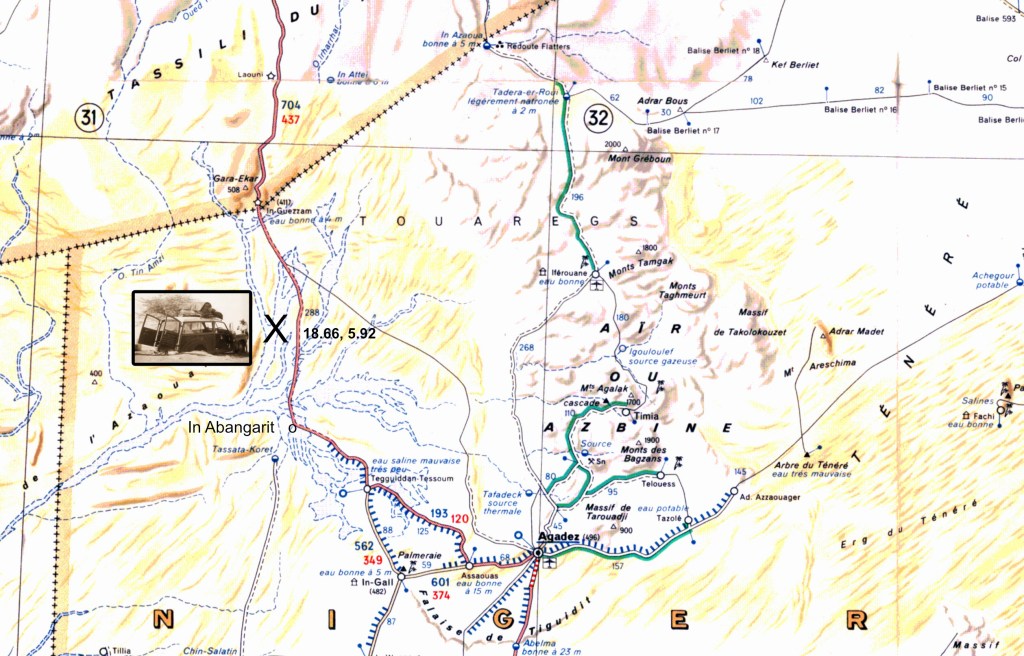

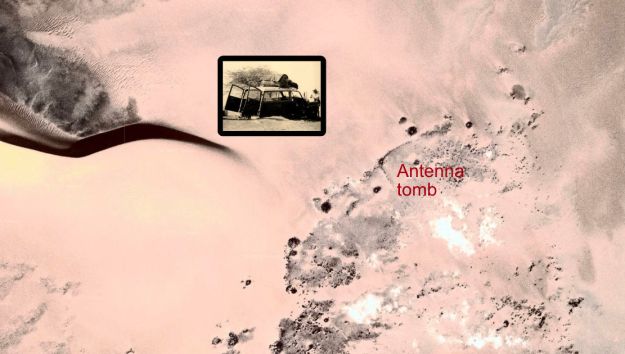

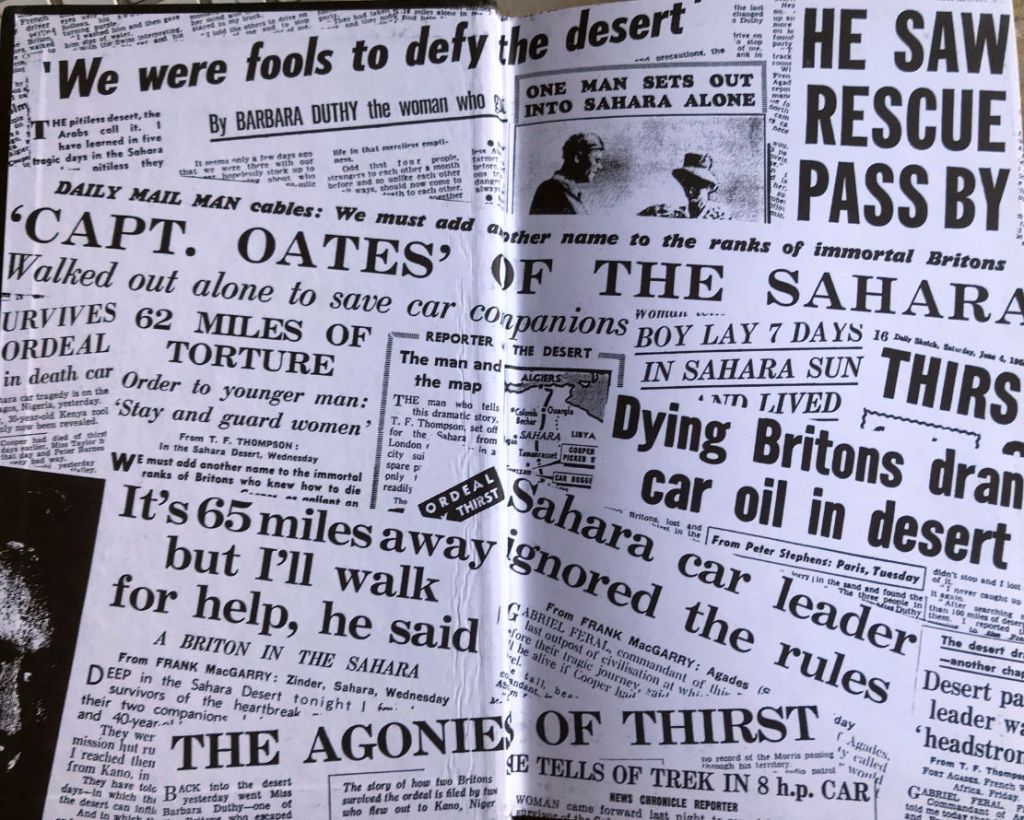

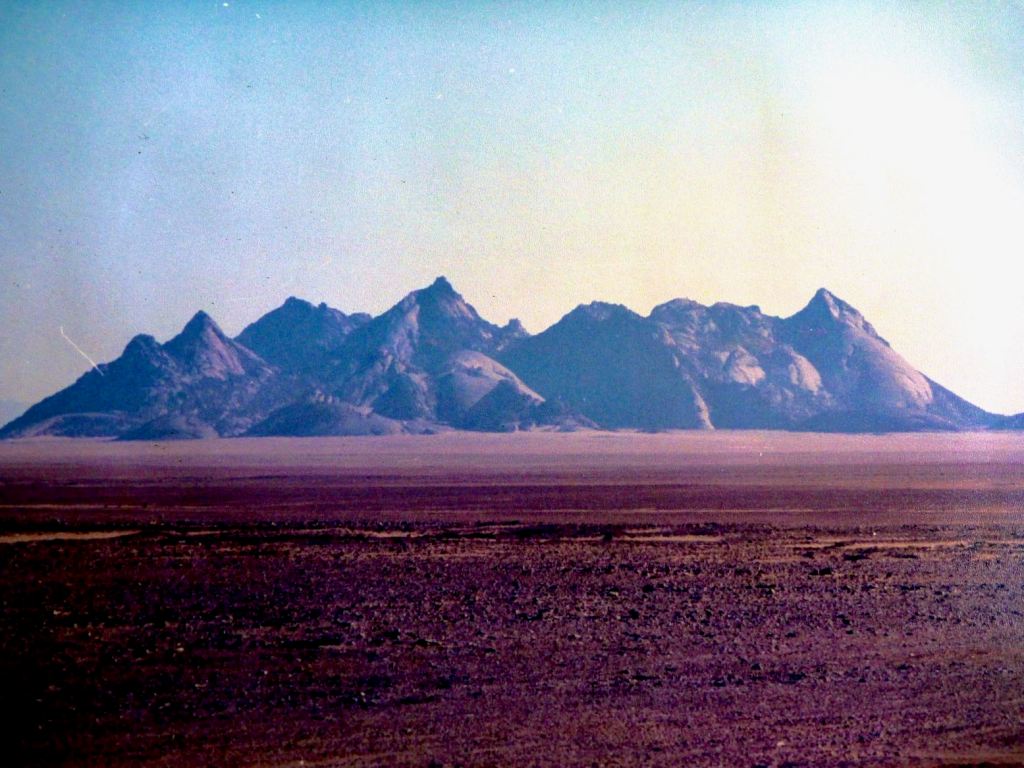

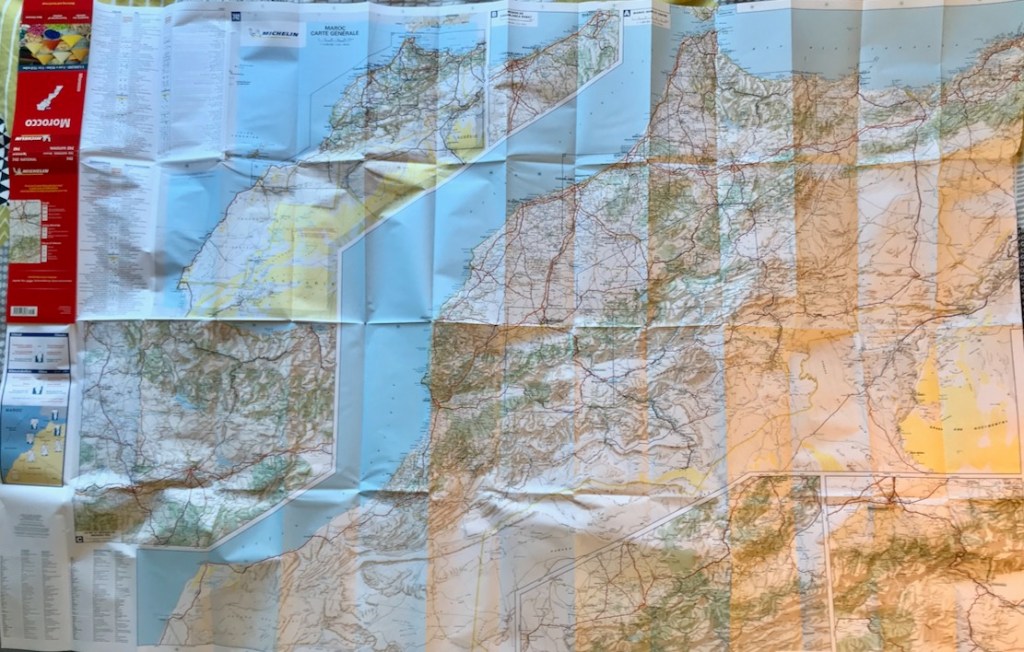

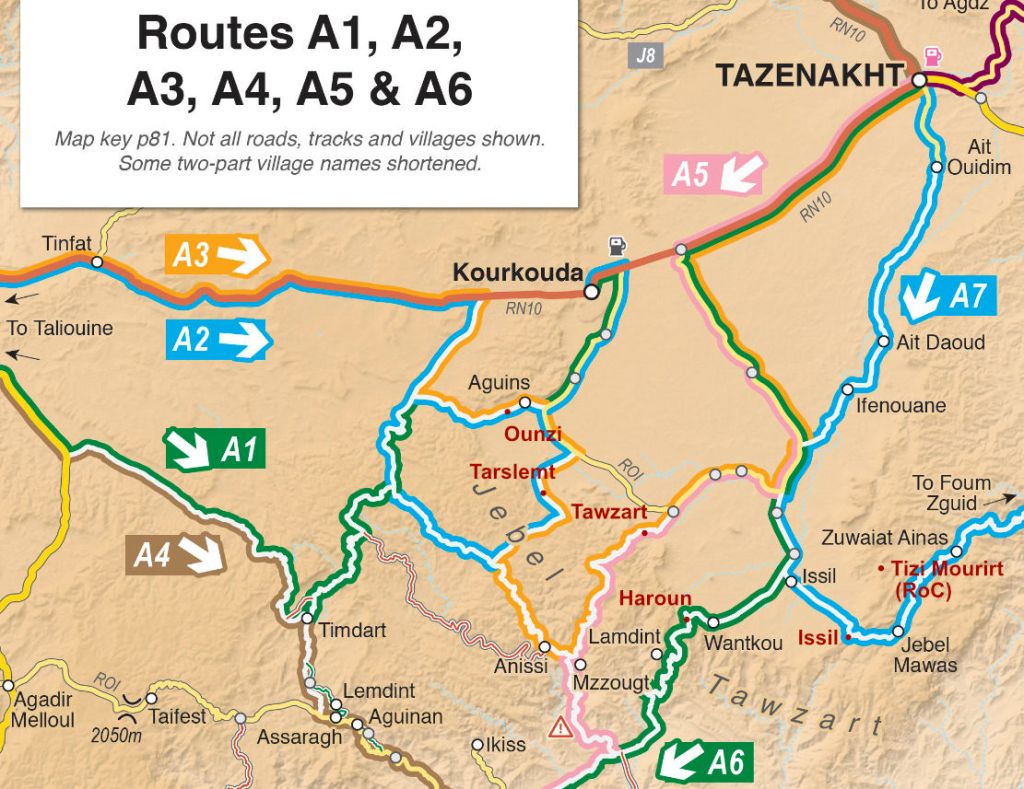

We were checking and adding to routes in my Morocco 4 guidebook as well as the Trans Morocco Trail. The last time Jon and I rode together was in 2003 out to the Tenere Desert on Desert Riders. Now that was proper desert. and here were proper mountains.

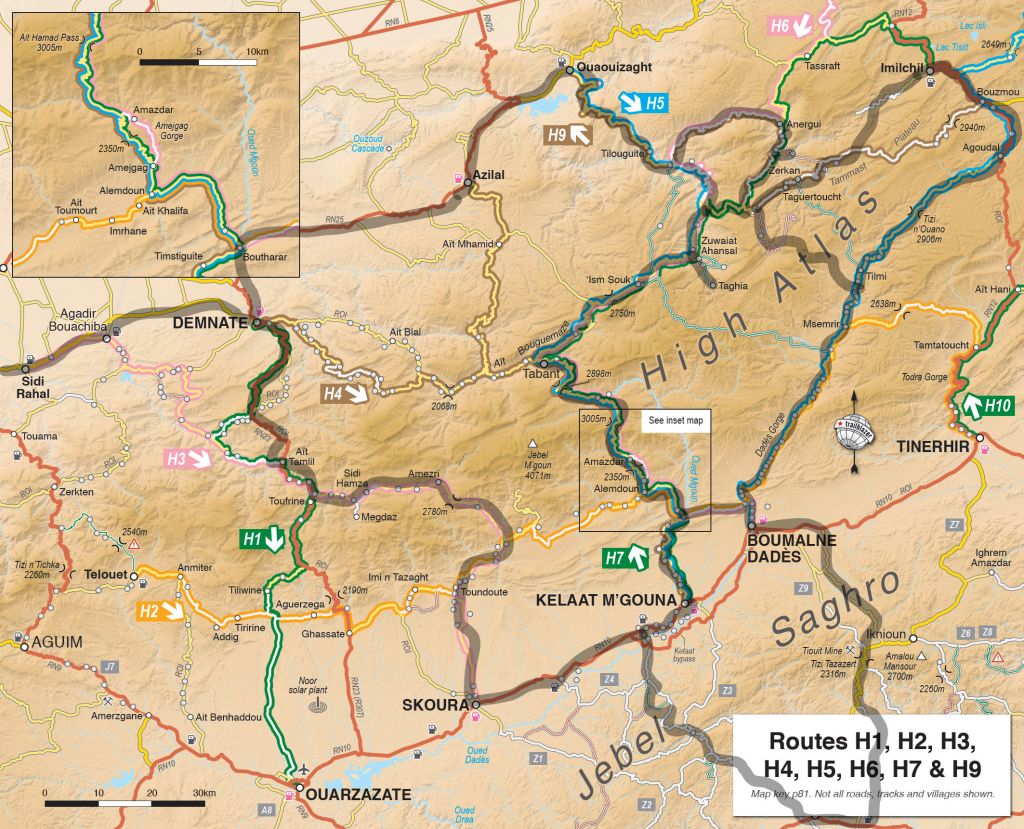

The night before we left Marrakech I’d failed to plan a good way out of the city, and now the Garmin was leading us straight into the souk on an updated OSM map I’d just installed, then routing more dumb detours off the main road to Demnate. I checked the Montana’s prefs; switching maps fixed things. We were on our way to Anergui, tucked in a remote High Atlas valley about 300km to the east.

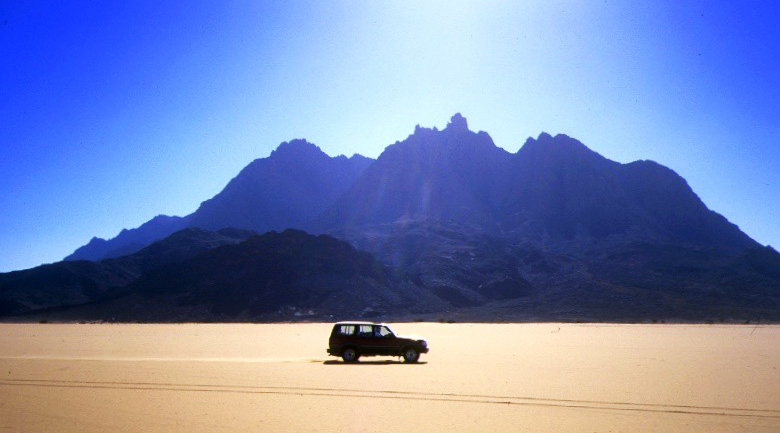

After a nous-nous in Azilal and the same for the bikes in Ouaouizaght, we passed behind the depleted reservoir and turned into the hills. Approaching Tilouguite, the last town, I was struck by the epic view (above) up the Imsfrane valley to the Cathedral crag and the Tammast plateau beyond. This would be where we’d be riding for the next few days.

The road ends near the bridge in Imsfrane, and the last 40km into Anergui follow the stunning Assif Melloul gorge (above; video below) which comes out into the Anergui valley.

At the Assif Melloul auberge we met up with TTR Simon, as well as a couple of Germans who’d both just discovered the TMT. The day before Simon had caught up with them on Stage N which had just become accessible after months, but they’d struggled along the gully, 32km from Bou Azmou. Acknowledging similar feedback from others, we’ve since rerouted the start of Stage N along a new road out of Imilchil.

The following morning the three of us set off for a day trip to the Taghia cirque behind Zawaiat Ahansal, taking the newly repaired climb south out of Anegui which in early 2024 James and I had probably been the first to descend (left), just before it was completed. The bridge at the south end of Anergui was already semi-collapsed following the September 2024 rains, but the track up to the plateau was now in great shape.

No yet bike fit, the short ride through the cleft into Taghia (above) was a bit rough, and by the time we popped back out, it was too late to be recce’ing new tracks, as planned, so we bombed back down to Imsfrane and back along the gorge to Anegui. On the way we met some French climbers heading for Taghia in a Duster rental with the same engine warning light we had a couple of years back. I assumed it was another loose turbo hose, but that looked fine which probably meant either a dodgy sensor or the turbo was on the way out. There might have been some life in it, but we advised them to turn back.

Next morning we took our third pass along the Melloul gorge, now lit by the rising sun, and in Imsfrane located the turn-off for the steep ‘Talmest VOR’ rising up behind the famous Catherdral crag to the snow line. I’d been wanting to do this one for years and the contours did not disappoint, with great views onto the back of the Cathedral and over watersheds to adjacent valleys.

We were only a little miffed when tarmac set in about halfway, at Igherm n Talmest to the Ahansal high road. At Ism Souk I asked some old men about the long, high track over to the Dades valley, but they pointed to the nearby snowy slopes with a shake of their head. Little did I know in a few days we’d find another way over to Dades.

Near Tabant we bought a couple of litres of fuel for the bikes then carried on over the snowy High Atlas passes down to Kelaa.

Near Alemdoun the other two missed the turning for the unsealed Amegag gorge route (above) which I followed, knowing we’d catch up. It’s a nice variation, but flood prone (hense the road over the pass). Within a couple of days it was washed out by rains again.

We’d taken a juiced-up version of Stage P on the Trans Morocco Trail but whichever way you do it, Anergui to Kelaa is one of the best mountain days you’ll get in Morocco.

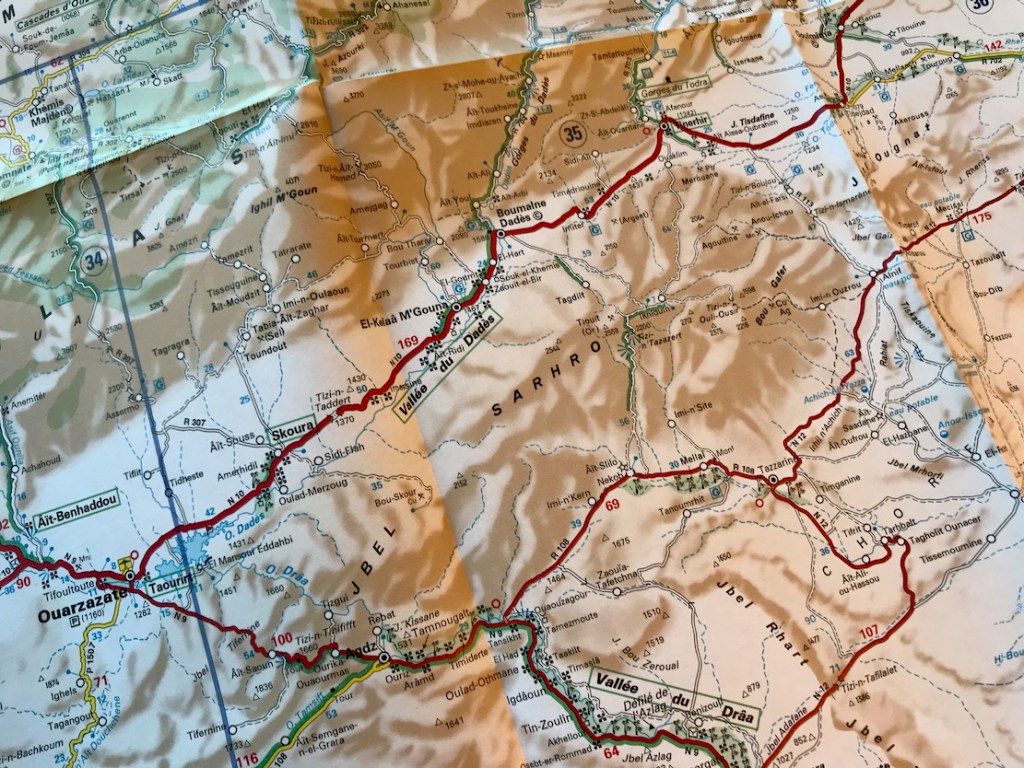

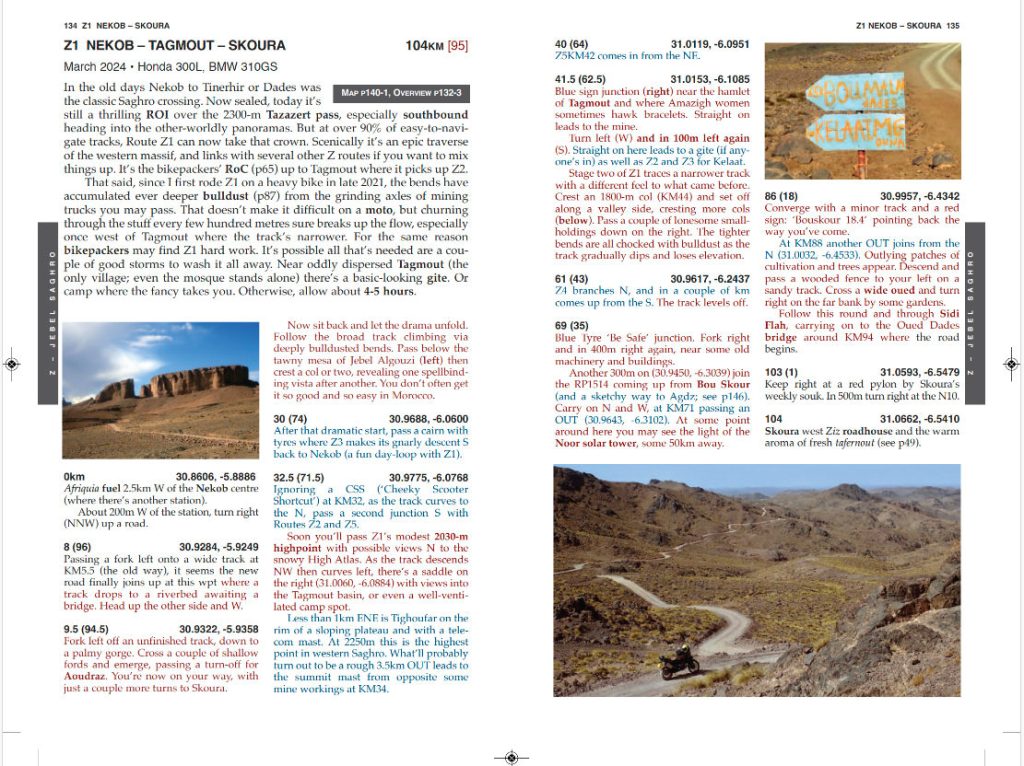

After overnighting near Kelaa, Simon headed back to Marrakech, soon running into TMT co-founder Ed Gill nosing about on his even older Yamaha XT600, while, Jon and I set off over Jebel Saghro to Nekob, along Stage Q or Routes Z2 and Z1 in reverse.

I’m convinced TMT Stage Q, southbound across Jebel Saghro, doesn’t do this mini massif justice, but anything else would pull the TMT even more off line. If people want them, better tracks are all there in the book or on the maps.

Arriving in Nekob, it was a lot warmer even if it’s still at 1000m asl. Down in the desert it would be baking. The morning’s track had given me another beating, leaving me with sore hands and a sore butt. After a nous-nous or two in town, we set of for our out-of-town auberge.

We swung back north to Imilchil next day, finding the Ouano pass finally sealed, making it the fifth sealed High Atlas crossing. After a long road ride, it sure felt nice not to have been pummelled by the trail.

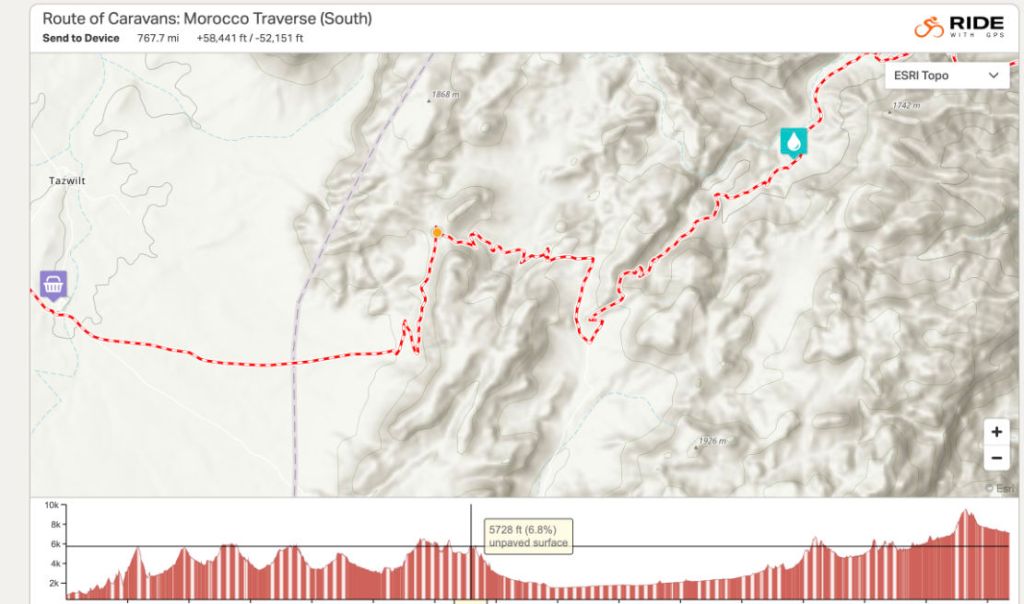

Still, none of that stopped Jon and me having a brilliant last couple of days in the High Atlas. We recce’d a new road start to Stage N out of Imilchil which now joins up just west of the troublesome gully, then followed the rest of amazing Stage N back to H9KM85. Here we took a chance and turned south along an old road that lead deep into the hills and seemingly ended at a remote village which is a dead-end OUT in the book.

But soon after we set off, two travel bikes passed us, which suggested either they’d also just tried and failed to get anywhere, or they’d found a way over the watershed from the Dades valley. No map I had showed this trail and on satellite, tracks went all over and who knows what shape they’re in. In the end, with a couple of correct turns, we managed to span a little known 50-km off-road crossing of the High Atlas back to the Dades valley, peaking at over 3000m.

We rolled into the riverside Auberge Tissadrine, just below the Dades hairpins. For 500D HB, it’s money well spent in this gorge packed with lodgings. From here, next day we took the H2/H6 short cut to the Rose (Mgoun) valley but found it pretty roughed up, though popular with supported MTB-ers. Annoyingly, I misjudged one of the two mud holes we saw in 3000km and dumped the Him which added to the sourness of doing this track and cost me 80 quid for a bent crash bar ;-(

Near Skoura, we could not fail to pop into the Inov roadhouse for a tafernout flatbread and omelette. That done, we swung north towards Amezri, reversing Route H3 which I’d not done since 2019 on my old Himalayan 411. I had a feeling they’d since linked the road along the gorge to Ait Hamza (H3KM126). Turns out I was wrong: they’ve extended it a bit, but it still involves a short stretch of flood-prone riverbed, as well as some precipitous tracks carved out of the cliff or on top of landslides.

It was a great finale to our High Atlas adventure, topped off by a night at the gite in Megdaz, a few km from where the road resumes. You have to leave your vehicle at road’s end and walk a stony village path for 400m. The price on booking was only 10dh, plus 100dh ‘tax’, but they made it all back on the dinner and breakfast. Nice to visit a new place and lovely village viewed from the rooftop.

All that remained was a blast up the N23 Demnate road, still chocked with roadworks, followed by brochettes in Sidi Rahal middway through a windy ride to Marrakech. All around the skies were darkening, bringing rains which were about to mess things up in southern Morocco for a few days.

In just one week I felt like I’d seen loads, had updates for just about every H route in the book, and tried out a bike which I won’t be buying. I’m already planning more mountain exploring in November, but I’m gonna need a lighter bike.