Part of the Sahara A to Z series

In the last decade of France’s colonial presence in North Africa, their part of Sahara was divided between three territories: Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco (‘AFN’), ‘AOF’ (French West Africa) from Mauritania to Niger, and ‘AEF’ or French Equatorial Africa which included present-day Chad.

One could travel the pistes across the desert between the Mediterranean coast and the Sahel, and even scheduled bus services traversed these ‘Imperial Routes’ to the sub-Saharan capitals.

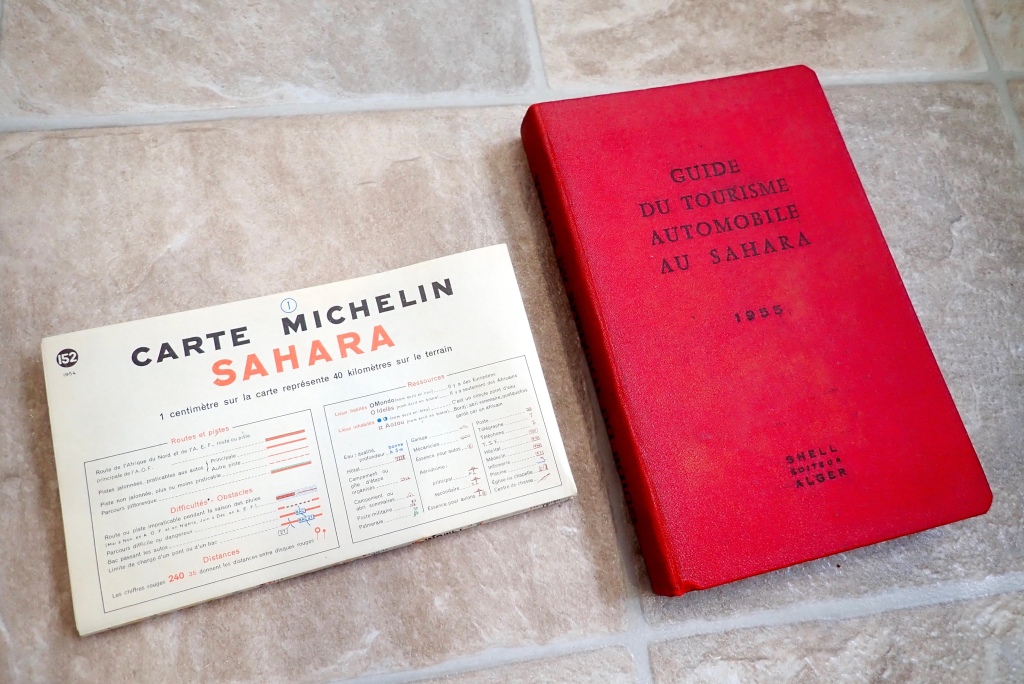

Just a couple of years before these colonies were dissolved and became the independent countries we know today, Shell released its fifth and final edition of the Guide du Tourisme Automobile au Sahara. The 345-page book is in French and there are still plenty around; mine cost me €25 from France, althpugh make sure you get the lovely map inside the back cover sleeve.

Originally published way back in 1934 (link to pdf) and just seven years after Shell started distributing fuel in Algeria, it must have been the first guidebook of its kind, preceding my own Sahara Overland by nearly seven decades.

The three pre-war editions (1934-5 pdf; 1936 below and 1938) were thinner books but also covered aerial tourism: fuel and landing strip information. Perhaps back then private planes were still seen as comparable or superior to with cars for getting to remote places. By the mid-50s commercial flying had taken off across the world, and flying around the desert was no longer a thing, unless you were very rich.

Even if it was nothing more than fully funded exercise in self-promotion, it’s still odd that an Anglo-Dutch oil company produced such a presumably prestigious project to showcase an important French colony, especially as it had the feel of an official handbook. In the 1930s Shell became well known for their illustrated guidebooks to Britain; perhaps publishing was not a thing that interested French oil companies like Total and Elf. Only Shell produced guidebooks, although road maps were widely branded by some of the oil companies of the era.

You can imagine the three French women (France Degand, Janine Delbert and Michèle Cancre d’Orgeix) had a copy of a Shell in the glovebox of their Peugeot 206 wagon before setting out their double crossing of the Sahara in 1956 (video below).

https://player.ina.fr/player/embed/CPF86641516/

The 1950s were the apogée of the colonial era when, even in the Belgian Congo, trains ran through the jungle on time and roads drivable by regular cars snaked over the equatorial escarpments.

In the Sahara pistes were well maintained, regularly patrolled and for the most part, well marked too. The Sahara still had its rough edges and expansive voids, but had been effectively tamed by the colonial administration, including a desert-wide network of Shell stations: ‘In the Sahara, as in your garage‘ the guidebook boasts.

It was the vestiges of this investment in desert infrastructure which we inherited in the 1970s and 80s by which time the whole region had seen 15-20 years of independent rule. The Shell emblem was long gone, replaced by nationalised fuel companies distributing the commodity with had become integral with global progress and development.

The Guidebook

Until 1939… the book starts… conditions for the harmonious development of winter tourism were coming together in the Sahara. Excellent temperatures, admirable sites, distant horizons, interesting populations, verdant palmeries [and] distinctive architecture: behold the country.

It then goes on to introduce the Sahara, using a flowery style which I’ve seen in more recent French guides to the Sahara. The book doesn’t miss a chance to include an exposition of the magnificent French achievements in the Sahara since 1919.

A year after this edition was published, after decades of searching (during which time French explorer and geologist Conrad Killian mysteriously met his death) prospectors finally struck oil in Edjeleh near In Amenas, and a short time later in Hassi Messaoud. By the end of the next decade Algeria became a major oil producer in North Africa.

It’s interesting to see how the content of the guidebook conforms with a modern day equivalent: a geographical breakdown of the desert’s geology, relief and topography, river courses and wells; ethnicities add up to either Arab or Berber, with pre-colonial history leading to exploration, colonisation and pacification right up to the period of the automobile and the aeroplane.

Short sections cover local artisans and the souvenirs they made, a bibliography, recreation and sports and not least hunting for hides, heads, horns and ivory. Happy days!

As for vehicle choice, the guide advised not to worry about using touring cars, by which I think then meant a regular RWD sedan or estate, like the Peugeot 206, above. Rightly it said the 4x4s of the time: Land Rover, Jeep, Willys and the near identical Delahaye V.L.R were significantly less comfortable.

It’s worth recalling that many regular cars of that era had bigger wheels and better ground clearance – garde du sol – ‘an important factor in vehicle choice‘… ‘Consider fitting bigger tyres, but not too much or you’ll stress the transmission and steering.’ ‘Power to weight is also a factor for tackling soft passages.’ …’avoid dual rear wheels…’ It’s interesting to see all these strategies were well known, even back then. It does however list a long and very heavy list of spare parts. Durability must be one thing that’s improved over the decades. In a way today’s SUVs have similar characteristics, but of course no one would consider taking one somewhere as outlandish as the Sahara, not least because 4x4s have improved to become much less utilitarian.

Code Saharien de la Route

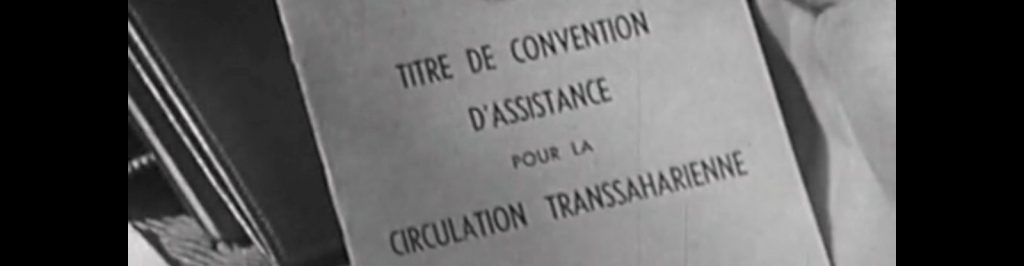

In that time of French control a detailed list of safety protocols needed to be followed before before setting off along a piste. ‘Pour votre securite‘ as they used to say to us in Algeria where the system endured into the 1980s (but without any actual back-up or support; you were on your own). The Code was a check on whether you were equipped to tackle what lay ahead, followed by the requirement to check on on arrival. If you followed the rules and were overdue, they’d come and look for you. You also needed some sort of contract with a local recovery service in case of a breakdown. The last 40 pages of the book detail the full list of these requirements for each of the three territories.

The Itineraries

The route guide breaks down the Sahara into four sections: southern Morocco along tracks which are now mostly roads. Then came the grandly named Imperial Tracks, starting with N°1: the Mauritania Line (above) which was recently reopened by Algeria. Back then, this was the direct route through all-French territory from Tiznit in Morocco or Colomb Bechar in Algeria, to St Louis or Dakar which circumvented the Spanish Rio de Oro colony on the Atlantic coast. Closed between June and mid-October, this was also the ‘Forgotten Path‘ which David Newman followed in his Ford Corsair touring car in 1959, just as the territories were breaking up.

The route description for the 2550km from Tiznit to St Louis goes on for 15 pages including a few photos and plain maps. It left Moroccan territory south of today’s Foum el Hassan, a small town between Akka and Assa on what I call the Desert Highway in the Morocco guide. I noted a passing reference to ‘Merkala‘; an escarpment watchtower marking the border between Morocco and Algeria which still survives as the enigmatic ‘Tour de Merkala’ on the Michelin 741 map.

In Tindouf we learn that prior to the French establishing a garrison in 1934, the settlement, had been abandoned for three decades due to persistent raids by the nomadic Reguibat. The Berbers must have welcomed a bit of law and order.

From here the lonesome track led to Ait ben Tili on the Spanish Sahara (today’s PFZ) border, with balises (marker posts) every 5km, but plenty of tole ondulee: ‘corrugated iron’ or washboard/corrugations to you and me. Like today, there’s nothing much for the traveller at AbT. Back then wild game added up to gazelles and long-gone ostriches. Once you got to Fort Trinquet (Bir Mogrein) you could add moufflon and leopards to that list.

From here it was 405km south to Fort Gouraud (Fderik) and the piste was poorly marked, sandy and rutted. The old route ran for another 310km from Fort Gouraud via Char fort to Atar didn’t get any less sandy, and the iron ore railway was still another 8 years away. Maybe a touring car, even with good clearance, wasn’t such a good idea after all.

Imperial Track N°2 was the Tanezrouft Line from Colomb-Bechar to Gao on the Niger river. This was the route chosen by the first cars to cross the Sahara in the early 1920s. It’s interesting to see how quickly the commercial drive towards tourism follows what was once terra incognita. You could say we’re seeing the same today in space; something which would have been hard to imagine in the middle of the Apollo programme.

It was on this desolate route that Bidon V (‘Oil drum 5’, below) made a name for itself as a desolate travellers way-station between Reggane and Tessalit in present day Mali. At one point the lighthouse shone into the night, planes could land for a refuel and a couple of bus bodies where parked up on oil drums to provide lodgings for passengers the Mer-Niger bus route.

The book continues with other well known routes in the Algerian Sahara, though not exactly what we have today. Imperial Route 3; the Hoggar Line – today’s Trans Sahara Highway – ran further east between El Golea to In Salah, and again on to the Arak Gorge where a friendly Shell bowser (left) stood by at your service.

From Tamanrasset, excursions up to Assekrem along today’s route were already established (fold out map included), and the now paved track to the border via Laouni was the same, but once in AOF, the track went straight to Agadez via In Abangarit to the south. It was on this route that the drama vividly described in Trek, met its climax. There was no Arlit until uranium was discovered there about 15 years later. Zinder, close to the Nigerian border, was the end of that road.

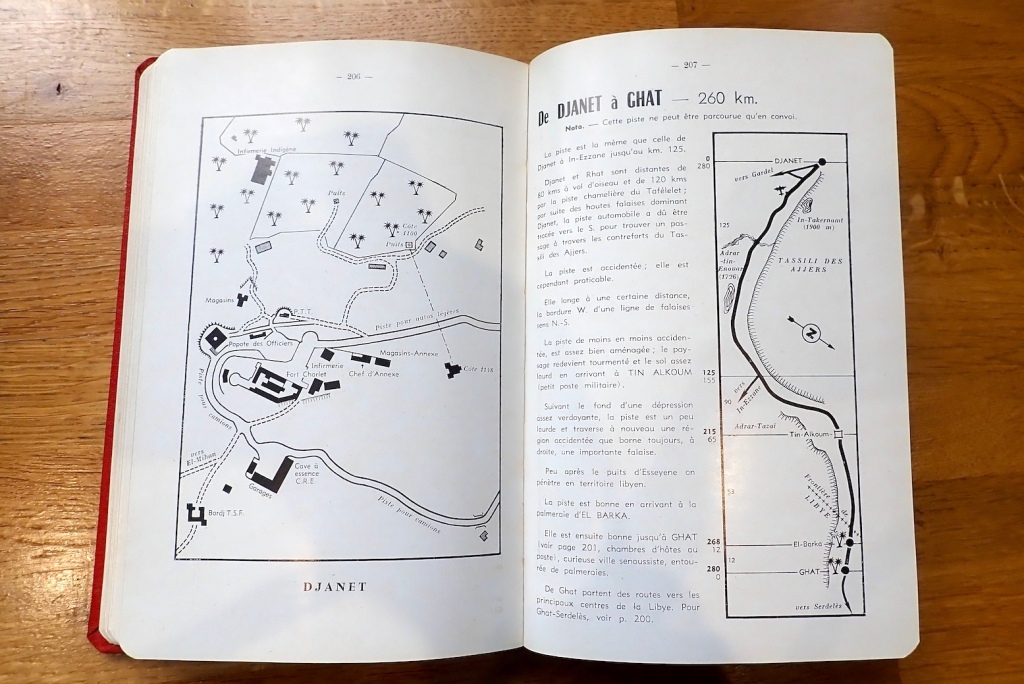

The Ajjer and Tibesti Line was Imperial Route 4: from Biskra all the way to Fort Lamy (N’djemana) in Chad. From Djanet the route dropped down to Bilma, the long established administrative capital of the eastern Tenere, before you back-tracked north to Seguedine to head east for Zouar, Faya and even Fada before turning down to Abeche and Fort Lamy. This was the route which the lavishly equipped Berliet expeditions of 1960 sought to open up for trade, just as France’s overt control over the Sahara slipped away.

Back then getting to Djanet meant dodging the Fadnoun Plateau (Tassili N’Ajjer). From Fort Flatters (today’s Bordj Omar Driss) you headed out over the sands southwest to Amguid, then southeast along the base of the plateau. Right up to the 1980s this was truck route to Djanet until they sealed the winding road over the Fadnoun which to this day still catches some truckers out.

If you could get to Fort Polignac (Illizi), a car route did actually cross the Fadnoun. You left Polignac to the east then either pitted yourself against the very sandy Imirhou gorge (left) , or all the way to Tarat fort on the Libyan border, before turning south to join today’s route at Dider.

On bikes for Desert Riders in 2003 (the full movie is on YouTube), this was a tough but epic ride across the tumbled escarpments of the Tassili which took us two hard days. But the time we reached the final descent from the plateau at the Tin Taradjeli Pass, we couldn’t wait for the sands of the wide open Tenere.

From 1943 up to 1951 the French administered the Fezzan province of Libya and may have had had hopes of annexing it. But by the time this edition was published, growing calls for independence put an end to that idea. Meanwhile. the northern deserts of Chad remained as obscure and little visited as they are today.

The Map

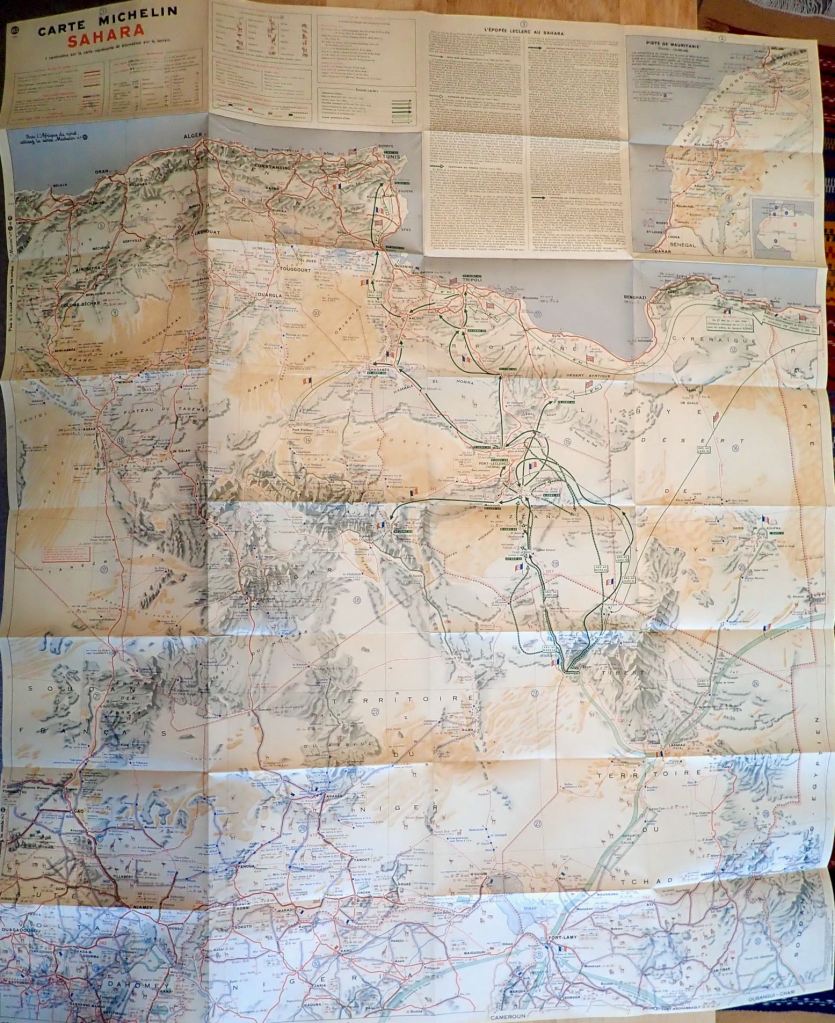

The Shell guide includes a 1:4m scale map folded into the back cover. It’s more or less Michelin’s 152 of 1948 which to some may alone be worth it the price of the guide.

It doesn’t have the full coverage of the 153 North & West Africa which came later, but shows the routes described, and much more. This detail has long made the Michelin map indispensable in the Sahara, even if it is a rather skimpy navigation aid to setting off along one of the Imperial routes.

The Mauritanian Line gets a 1:9m inset (below left) while in Libya (never a French territory) the map proudly shows the routes of General Leclerc’s desert campaign during WW2 which ended in the famous raid on Murzuk in co-ordination with the Long Range Desert Group.

Pingback: Maps of the Sahara | Sahara Overland