Part or the Sahara A to Z series

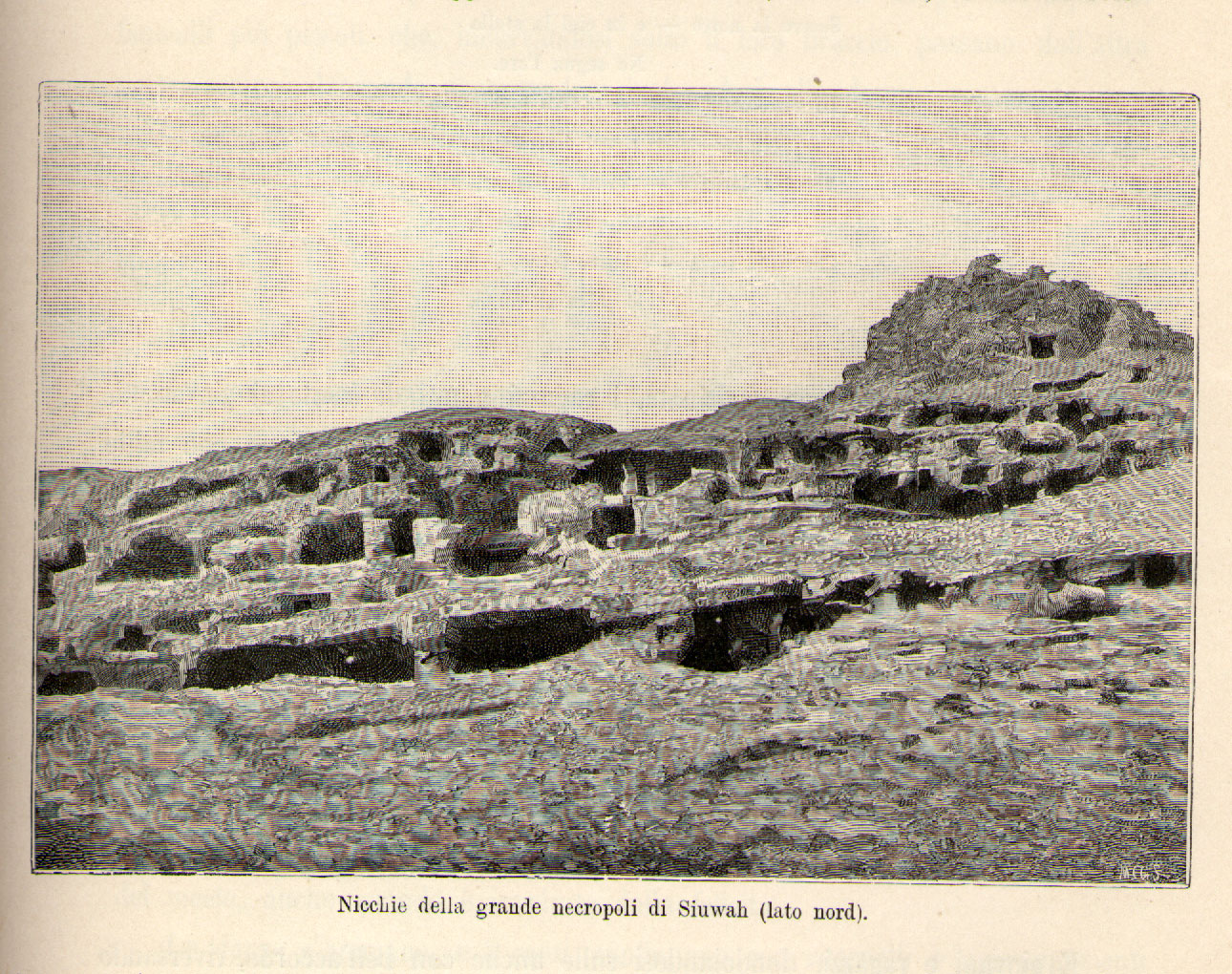

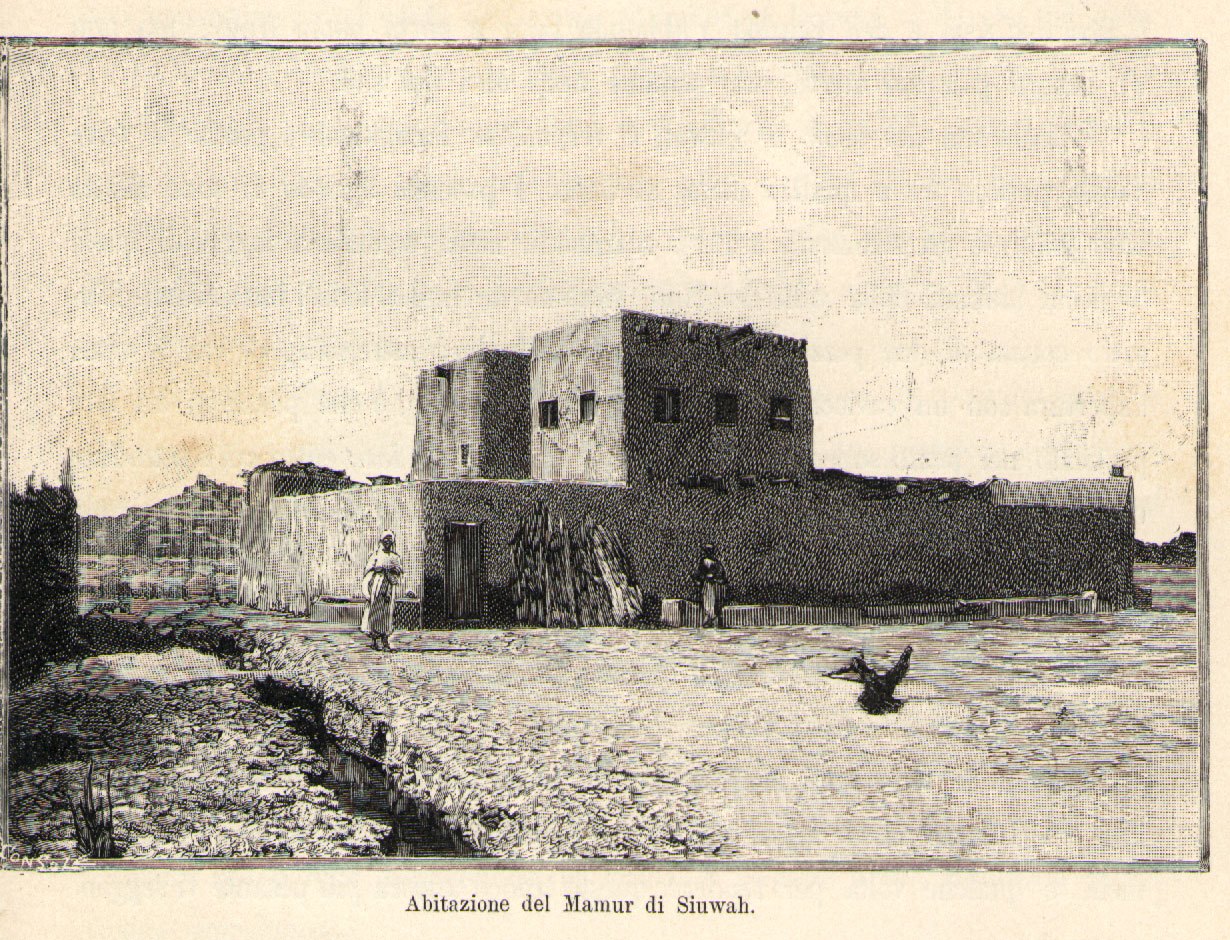

Taken from the book All’oasi Di Giove Ammone

(At the Oases of Jupiter Ammon)

by Luigi Robecchi-Bricchetti (right)

Part or the Sahara A to Z series

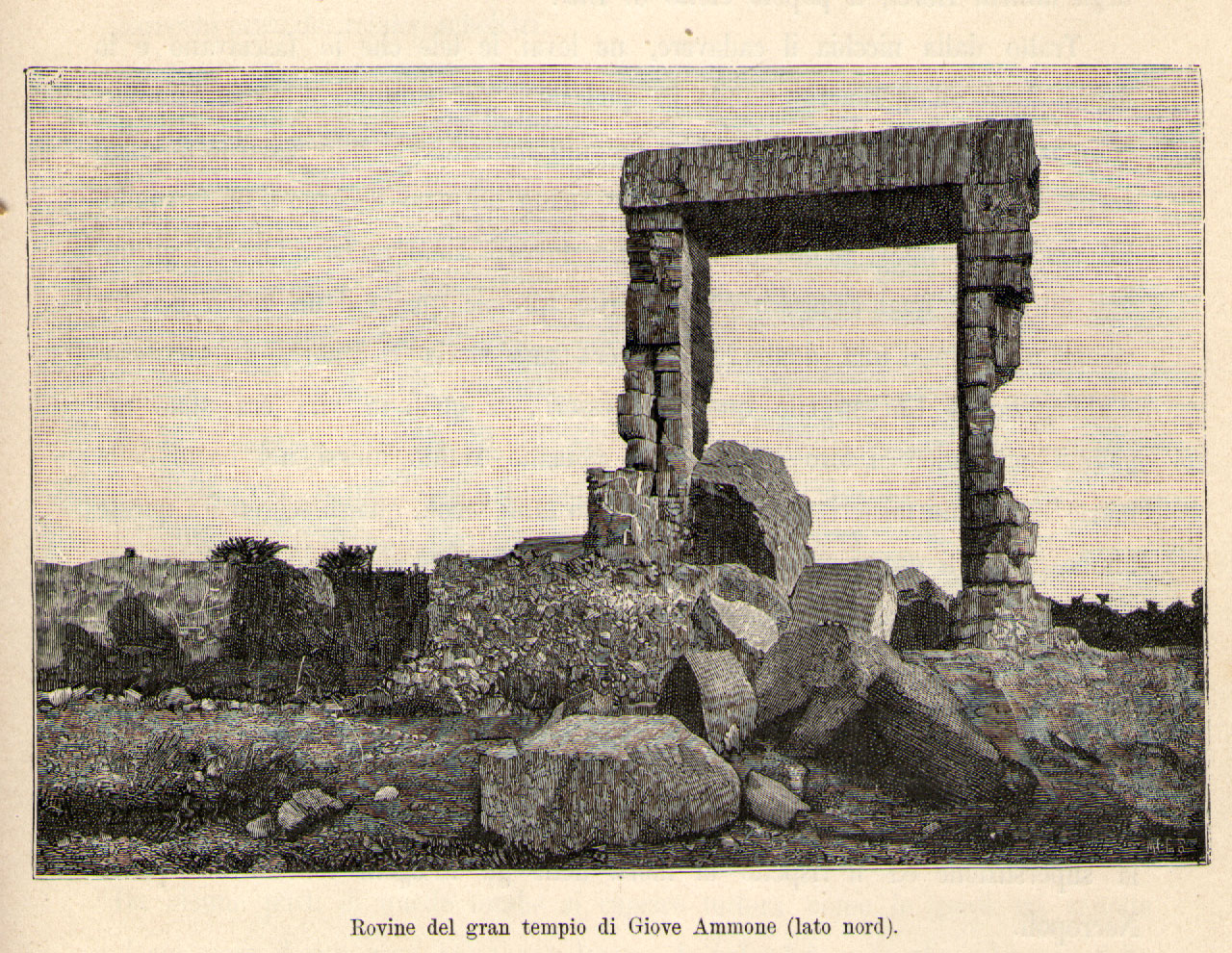

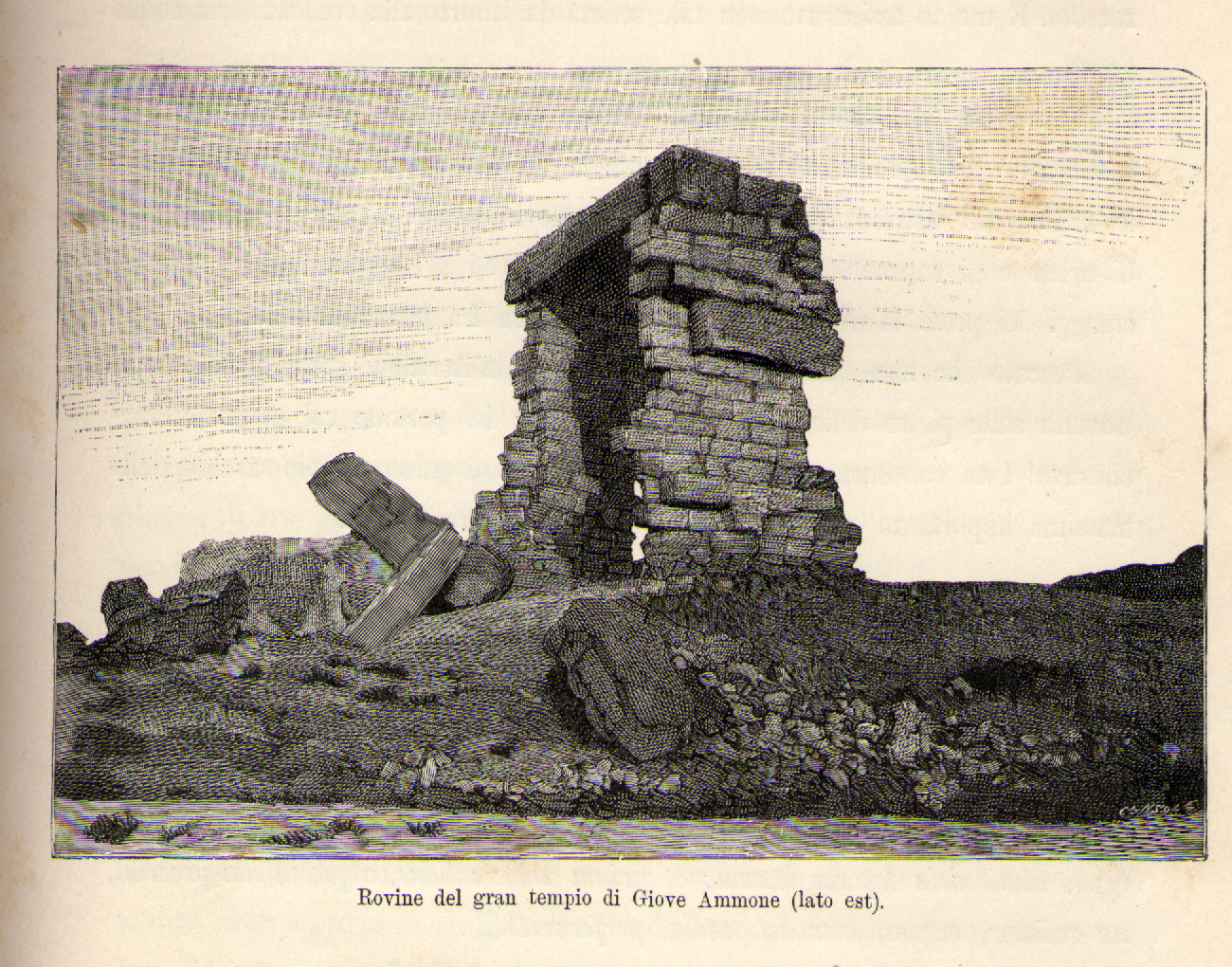

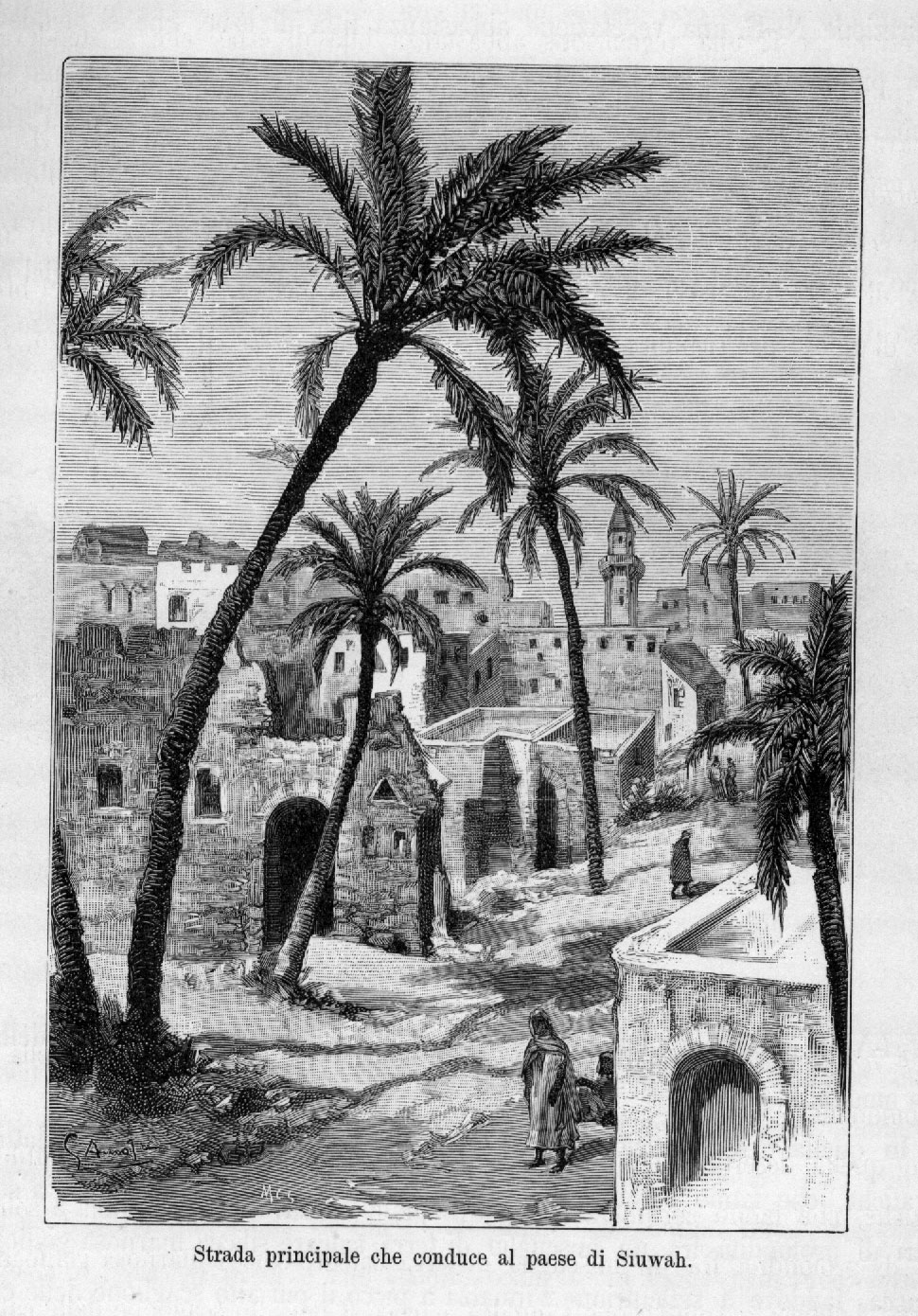

Taken from the book All’oasi Di Giove Ammone

(At the Oases of Jupiter Ammon)

by Luigi Robecchi-Bricchetti (right)

Tunis

We left Marseille on 10 December ferry to Tunis. The ferry was only about 1/3 full making the loading in Marseille uneventful compared with our trip a week closer to Christmas in 1999. The ship docked in Tunis at noon with clearance through Tunisian immigration and customs taking a mere 30 minutes (compared to 5 hours in 1999) allowing us to reach the salt pan of Chott El Jerid near Nefta (Algerian frontier) shortly after dark. We camped on the salt pan, leaving early for the border crossing the next morning.

Algeria

Clearance out of Tunisia took about 30 minutes but entry into Algeria just over 4 hours. In that time the officials processed only 3 cars, two of which were Algerian. The officials were nevertheless friendly. Two German bikers were crossing into Tunisia as we were leaving. They had ridden a loop from El Oued to Djanet then onto Tam and back along main route through In Salah (which included a convoy).

The Algerian border formalities correspond exactly with those described elsewhere on this website (immigration, customs, compulsory money change and car insurance). The only problem we had was with customs insisting on us filling in the form to reflect ‘Landrover’ as the type of car but ‘Toyota’ as the make. I guess this finally signifies the death of the British automotive legend, in this part of North Africa at least. [It was the same story with one of the LRs on my tour too, but caused no probs. CS]

From the Algerian border we headed on towards El Oued. There seemed to be few camping possibilities along this stretch given the awkward hummocky dunes lining the road and the proximity of villages. About 20 or 30km from El Oued, while entering one of the small villages, a group of youngsters aged less than 10, stoned the Landrover. No windows were broken but a bit more topography was added to the body work – never a serious issue in a 30-year-old vehicle with an aluminium body. We were welcomed into El Oued by the police and local businessmen alike. El Oued was calm and the streets clean and quite empty. We changed money at one of the banks.

That night we slept on the south side of the road 60km short of Hassi Messaoud. A strong north-easterly was drifting sand in a conveyor about 1m deep so we were looking for shelter behind south-facing hills. There is a small escarpment out of view of the road (N32° 10′ 37” E5° 52′ 23”) which served the purpose on a stretch that offered few alternatives. We arrived in Hassi shortly after 8am the next day. Here the military checkpoint issued our laissez passer in about 20 minutes. It was valid for a month. We were waved through the south side of Hassi en route to Hassi Bel Guebbour. The next check point was at Gassi Touil. Here the military spoke very little French, but seemed to want us to return 3km and wait at the side of the road. We went back, found nothing at the road side and so returned to the checkpoint. After a bit of discussion amongst themselves we were eventually waved through. We now know that a convoy operates on this stretch and may entail a delay of several hours until the convoy leaves.

If you have ever looked out of the window of a 747 on a night time trans Africa flight and seen two tiny pin pricks of light in the insanely massive blackness of the Sahara, the chances are that you are looking at somewhere like Hassi Bel Guebbour – with the two lights shared between the fuel station and the shop, this being the first fuel after Hassi M. It has a great sense of isolation and the interdune corridor that the tarmac follows south from Gassi is stunning.

Some 50km east of Bel Guebbour (28 36′ 10”N, 7 5′ 27”E) we passed large pools of water in an otherwise dry river bed. Although it was fairly early in the day we couldn’t pass the opportunity by and so set up a pleasant camp a few kms clear of the road out of the still strong north-easterly. A piste runs south to Bordj Omar Driss which starts parallel to the road [I have been told to avoid this piste – plenty of oilfield security].

The next day we called in at In Amenas (the bakery was selling awesome custard slices) and headed south through the huge dune field which seems to be the far western limb of the Ubari sand sea, eventually camping off the road in a sand field in the lee of a shady glade of trees (N26° 56′ 23″ E8° 41′ 54″). Firewood was plentiful. From our campsite we drove early the next day to Illizi for fuel and then on across the Fadnoun Plateau. The new road is a bonus but twists sharply without warning. It is rather like a pub video game where a blind rise could be followed by a sharp left, u-turn or a stranded truck jack-knifed across the road. The whole route from Illizi to Djanet is beautiful. We camped about 100km short of Djanet in a large dry river bed (N24° 54′ 56″, E8° 45′ 87î”). It was a stunning setting and well worth a few weeks stay. In Djanet we had a pleasant stay at Hotel Zeribas, camping in the far corner under the reed shelters. Djanet offered a great selection of fresh veggies, telephones which work given a bit of patience and pleasant temperatures. South of Djanet the daily temperatures were well over 30 degrees.

Whilst settling down for a quiet brew of tea in our campsite at Hotel Zeribas, Andy Pag drew up in a blast of diesel from the old Datsun he had brought down from Belgium. By this stage he was travelling alone and therefore keen to join us across the Northern Tenere to Chirfa and Dirkou. This was the planned next leg of the trip. We were glad for his company because the piste from Djanet to Dirkou is a lonely 850km stretch (we passed no traffic on this entire route).

Although our time in Algeria was much shorter than planned (for reasons explained later), we found the country calm and enjoyable to travel in. The only military checks we passed through were at Hassi M, Gassi Touil, and Hassi Bel Guebbour. Apart from this stretch, we were free to come and go as we pleased. Whenever we encountered police we found them very helpful and accommodating. From a tourist perspective, everything is in place for Algeria’s recovery – all that is missing are tourists. We saw none between the Tunisian border and Agadez (about 5000km) except for Andy in Djanet.

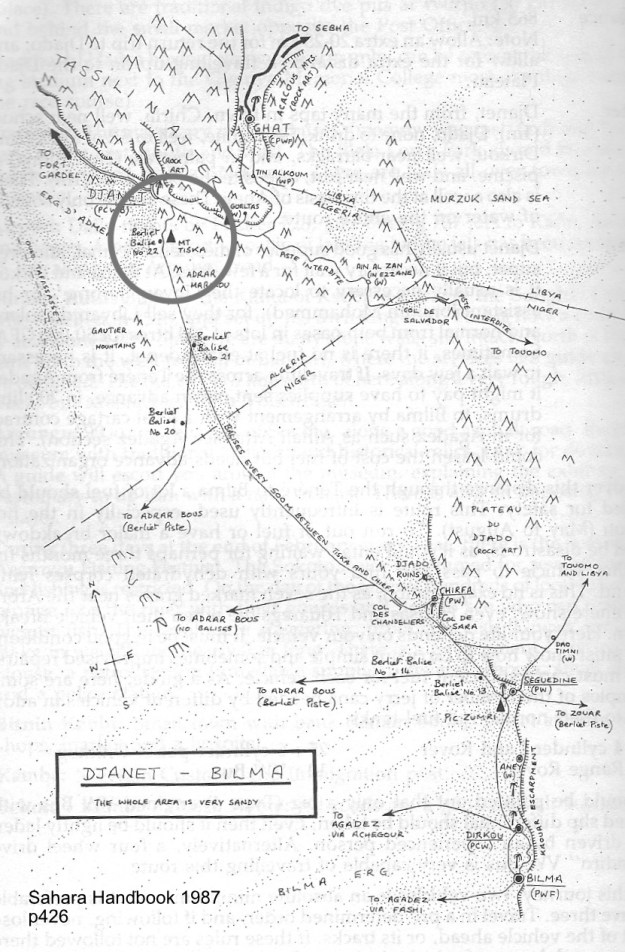

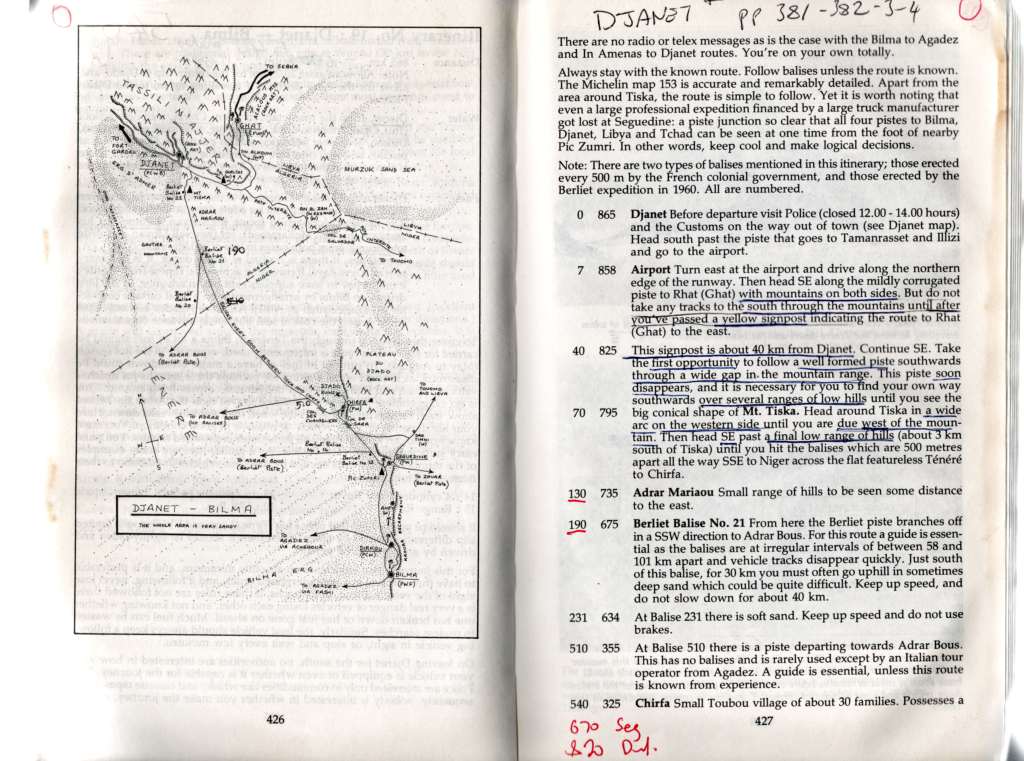

After some time to rest and check out Djanet, we took off for Niger, leaving by the piste to Libya (a left turn off the new airport road past the old aerodrome). We turned off this mildly corrugated piste about 35km from Djanet, taking tracks through a gap in the mountains towards Mount Tiska. Once the tracks join, the piste is surprisingly well formed. After about an hour (roughly 40km) the piste turned east of Mount Tiska. The area is very beautiful with just about every spot a perfect campsite. We spent the night here with Andy cooking up a great veg stew. During the night we saw three vehicles approaching the Mount Tiska foothills some 10km to the south. They stopped when in view of our fire although we couldn’t be sure they saw us. They set off again well after midnight once the moon was up, passing within a few kilometres of us with their lights off. This all seemed to point to smugglers bringing Marlboro cigarettes into Algeria, possibly via a piste through the Djado plateau.

We continued on the well-formed piste the next day. Within an hour it was obvious that the piste would pass well east of the Adrar Mariaou. The piste is not marked on the Michelin or the TPC maps. Since we wanted to hook up with the balise line across the northern Tenere (which lies west of Adrar Mariaou) we left what seems to be a smugglers’ piste, taking a drainage line out onto the flat northern Tenere. The surface was better than any tarmac we had driven since France. While the route sounds complicated, the desert is very open with the Mount Tiska and Adrar Mariaou mountains clearly visible all the time. All the driving was easy. Within an hour we had gained the Tenere and found the first balise. There we several old (and a little indistinct) tracks along the balise line. Our GPS position showed us to be on the eastern most of the two pistes entering the Tenere which are marked on the TPC J 3B map. As the balise line piste appeared to be the western most piste on this map, we seemed to be on the wrong line, and so headed south-west to see if we intersected any other piste (although we were sure that there was only one balise line across the Tenere and that the TPC marked piste was wrong – but the check was easy to make and the surface pretty hard). It turned out that the piste marked on the TPC is wrong.

After about half an hour four Toyota Land Cruiser pick-ups could be seen driving straight at us from the northern base of the Adrar Mariaou mountains. They were travelling at speeds up to 160km/hr. The group turned out to be the Algerian police. After making their AK-47s clear to us and checking our papers (carte de grise, visas, insurance etc) they waved us on cheerfully. We should point out that it is not possible to leave Algeria officially along the northern Tenere route south of Djanet. While the police don’t mind, the Algerian customs do not permit official exit.

The northern Tenere is simply awesome. It is difficult to put words to the vastness of the place. It is impossible at times to tell whether you can see 50m, 500m or 50km off the piste. There are three wrecks on the balise line, two from the 1988 Paris-Dakar race. The shot-blasted dark silver chassis gleaming in the bleached light. For the most part the northern Tenere is very easy driving. The first few hundred kilometres out of Djanet were softer, the Landrover not being powerful enough to plane over the surface. Immediately south of Berliet balise 21 the sand becomes deep and powdery. It was the only time between Djanet and Agadez that we needed low range. The soft sand persists for 40km south of Berliet Balise 21. In a newish Toyota the northern Tenere could probably be crossed in a day. We took two days of driving, but three days altogether.

Niger

The exit from the northern Tenere to Chirfa is clearly marked – nearly all the balises are in place across the orthern Tenere. On arrival in Chirfa we drove directly to the military checkpoint. They stamped our passports while looking over the vehicles, asking if we had any sat phones, short wave transmitters as so on. We helped the commander with his GPS as he had no manual for it. We left our passports with the military overnight, thinking that this was routine practice in Niger. We drove through the village and checked out the impressive Djado ruins. The next day we returned to the military post for our passports. By then the mood had changed and we were ordered to drive directly to Dirkou, not to leave the piste and to arrive there no later than 4pm. As it was already getting on to 10am it was a tall ask in our old vehicles. We assumed Dirkou was the first official border post (as marked on the Michelin map) on this route and hence the requirement that we shouldn’t linger on the piste. We found the piste south of Seguedine very sandy. Again it would be very difficult to get lost on this route – in fact we hardly bothered with the GPS. We arrived in Dirkou a little after 4pm, handed over our passports (which were again kept overnight), met with Jerome [the fuel trader] and drove off to town for the night. The military checkpoint was pretty chaotic as several 10-wheel-drive Merc trucks loaded to the hilt were about to leave for Libya.

We returned to the military post early the next day, waited around before asking for and being given back our passports (they now had stamps from both Dirkou and Chirfa). From there we headed up the hill to refuel (we had used about 220 L of petrol since Djanet; that’s 3.7kpl or 10.4mpg) at Jerome’s fuel dump. Make sure you take your own pipe / 12V pump as Jerome’s assistants seem to have sucked too much fuel through their brains over the years. They are several sandwiches short of a picnic!

Whilst we were refueling the military drove up in a Landcruiser and took back our passports and vehicle papers. Once we had finished refueling the military impounded our vehicles. We now had no passports, no vehicles and no vehicle papers. Things weren’t looking good. No explanation was given but we were told to wait until 3:30pm. We waited in a barbed wire area between the passport shack and the military base. This is a stinking hot, dusty, shadeless area surrounded by feche feche that we grew to hate over the next few days. At 5pm were we told that there was a problem and that we would have to wait until 9am the next morning. We later found out that the Minister of Defence in Niamey had already phoned the French Ambassador in Niamey to say that European nationals were being held in the north. The French Embassy in Niger deals with all European nationals in Niger.

The next morning we were told to wait until 3:30 pm as the commander of the military base in Dirkou was waiting for instructions from Niamey. Most of our dealings had been with the Chef de Transit at the passport shack on the outskirts of the military base. He had been telling us all sorts of lies about why we were being held and when we would be released. He was a very difficult person to deal with – at one point gesturing to me that he would tear up my passports if we didn’t leave him alone. Our main effort at this stage was to speak to the Military commander of Dirkou. Of course we could get nowhere near his office. Our vehicle papers, passports and visas were all in order and we wanted to know what we were being held for.

The commander finally agreed to see us late that afternoon. It was rather like meeting Kurtz. We were shown into this darkened, blue room with padded doors. The commander greeted us and asked what our problem was as he had heard we were anxious! We explained that our vehicle papers, passports and visas were in good order and that we were uncertain what the problem was. He explained that the situation in the north is difficult, that tourists coming into Niger from the north were a problem and that the only way to enter this region was through Agadez where all the necessary paper work was available and where guides could be hired. He assured us that he was working on a solution for us. We asked if it was possible to simply deport us from Niger and we would leave immediately back to Djanet the way we had come (this had been our plan all along).

Fortunately we had managed to get permission to be taken to Bilma (45km to the south) to phone our embassies. With our vehicles still impounded we had to find a way of getting there. The distinction between who was military and who was a tour operator was extremely blurred. We were charged 30 quid one way for the trip although we returned with a tour operator anxious for our business. They were an unpleasant mafia-like gang and things turned sour shortly after they dropped us off. Interestingly, we were taken to the military commanders office in the military base in the same tour operator’s Landcruiser. In Bilma we managed to call the German consulate in Niamey (there is only an unofficial representative for British nationals who is a businessmen in Niamey – he didn’t want to know our case!). I managed to get a line out to my wife who was in Cape Town at the time. Megan phoned the German and British Embassies in South Africa as well as the German Consulate in Niamey, eventually being put on to the French Embassy in Niamey. This helped our case enormously, although we had no way of knowing she had achieved all this until our problems were nearly over.

Early in the afternoon of our fourth day in Dirkou we were told that we were being taken to Agadez. Remembering that the Commander of the military camp in Dirkou had told us that Agadez had all the services necessary to help us, we were relieved that the problems from their side seemed to be coming to an end. This soon changed when a Land Cruiser with a machine gun and live ammo chain mounted on the back rolled up. They were our escorts, so at least we didn’t have to take a guide! Our passports were still being held, so it was clear we were simply being transferred to Agadez. We protested that our 30-year-old series 2A was not up to the Dirkou to Agadez crossing of the Tenere, but we were told that there was no option: take the vehicle or leave it behind. It was do or die time for the 1950s transmission.

We left Dirkou at about 4pm. Although there was still problems to come, it was good to leave that stinking hot, dust riddled, barbed wire camp. The military Land Cruiser drove in front but waved us past in frustration at our pace. We drove on to the wells at Achegour which we reached by about 7:30 pm. It was amazing to be crossing the central Tenere although it was a pity it was not in circumstances of our own choosing. We drove through the night, following a star but basically heading west south-west. Again we didn’t bother with a GPS. With no sign of the military we decided to savour our freedom and drove on into the morning light taking a dune corridor about 30km north of Arbre de Tenere (make sure you are in the correct corridor if you want to see this place otherwise you need to back track about 30km). The going in the central Tenere is much softer than the northern Tenere. Our consumption dropped to about 3km per litre [8mpg]. We hardly ever got out of second gear although we didn’t ever get stuck. Where the sand is very soft all the truck tracks merge. Apart from a very high median strip the going is OK on the tracks.

We emerged from the sandy desert at about noon the next day to find the military waiting for us. The piste is up to 50km wide in the Tenere so they must have passed us in the night. We drove on to Agadez arriving in the early evening. The commander of the military camp in Agadez then met with us. He simply said that after a day’s rest we would be taken on to Niamey 900km away. This was probably the low point of the trip! After a few days we had another military escort down to Niamey. We left on Christmas day at 9am and arrived in Niamey at about 8pm. We had a young soldier in our Land Rover but separated from the others over the distance. We were held at the outskirts of Niamey as our passport were in the other vehicle. Then we decided enough was enough and I negotiated for a passport substitute, giving them some paper with work letter heads. From there we basically made a run for the French Embassy – the soldier protesting from the back of the Land Rover while we made out we didn’t know what he wanted us to do. We arrived at the French Embassy at 11:30 pm Christmas night and were greeted by the French Ambassador, the head of the French Military attache in Niger and the Head of the Internationale Police in Niger. They were all amazingly helpful. Details began to emerge that we were suspected spies/gun runners. The piste from Djanet to Chirfa is never crossed from north to south these days and so our arrival out of the northern Tenere had aroused much suspicion. There was also a suggestion that we had been picked up by a military patrol in the Northern Tenere. This might have been the commander at Chirfa trying to win himself a promotion, but it was certainly not how it happened as we had driven directly to the military checkpoint at Chirfa and found them all lazing about in the sun.

A meeting was set up with the Niger Chief of Police for the next day. The arrangements were made from the French Embassy shortly after midnight. We were very surprised when the meeting went ahead as it was taking place at lunchtime on the Islamic equivalent of Christmas day. It was at that meeting that our passports were returned. We had been held for nine days and had been required to drive about 2000km for the ceremony. The Chief of Police of Niger pointed out to us that he didn’t know why we were being held by the Military.

From Niamey we took the shortest route out of Niger – to Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso.

So if you want a trip across the Tenere from Dirkou to Agadez without the official guide, then just cross the northern Tenere from Djanet to Chrifa and the military is bound to oblige. The downside is that the trip goes at their pace! Our original trip had been planned to take in Libya, Niger and Algeria, so crossing the northern Tenere from south to north. Others have done parts of this route. Although the Niger military clearly don’t like tourists in the northeast, they seem to tolerate the route this way round. Our plans had to change when the Libyans refused our visas.

Route

Genoa – Tunis – Nefta – El Oued – Hassi Messaoud – Hassi bel Guebbour (HbG) – Quatre Chemins – Gara Khanfoussa – Ain el Hadjadj – Illizi – Iherir – Djanet – Tadrart (Oued In Djerane, T-in Merzouga) – Bordj el Haouas – Serenout – Ideles – Hirafok – Assekrem – Ideles – Tefedest east (Garet el Djenoun) – Erg Amguid west – HbG – El Oued – Tunis.

About 2500km off-road

Vehicles

Land Cruiser HJ61, Land Cruiser HDJ80, Discovery Tdi and three 110 Defenders.

Ferry and Tunisia

It’s still the same story on the Carthage as described in the book, hours of queuing for forms. Not all of us got our Permit de Conduire before the ship docked, but they were quickly obtained from the Customs booths once in the port.

Before that, at the police booths in the first shed it helps not to imply you’re transiting Tunisia fast for Libya or Algeria. To keep them happy make out you’re spending some time (and money) in Tunisia too. One of our group got tricked on the exchange; led to a certain bureau de change by one of the orange boiler-suited guys. Be alert, they’ll get you if they can. And another was told to pay 10 dinars for his Permit de C. (it’s officially 1d or free on the boat).

Fuel prices in Tunisia: Diesel 41d, petrol about 70d.

We covered the 470km from Tunis to Nefta in about 8 hours and stayed at the Hotel Marhala in the zone touristique west of town, opposite the Caravanserai. Half board was around 40d for two people. It’s a clean new hotel with unusually good food (but what isn’t after the Amilcar in Carthage?).

The Border

We set off at 8.30am hoping to get a good start into Algeria but the border still took most of the day. The Tunisian frontier at Haouza was pretty straightforward. At Taleb Larbi on the Algerian side things move slowly. You do police forms for you and your car (white and green forms), move on to the Customs declaration (currency and valuables like video cameras or whatever you profer/they find). I was aware of the binoculars (jumelles) ban but was careless in hiding them and so they were confiscated with a receipt and returned on the way out. The others hid their binoculars better.

Each car was searched with a few suggestive jokes about whisky, but bury it deep and they won’t find it because you don’t get taken apart as can happen to locals. With your carte gris (vehicle logbook) you then fill out a Titre de Passage en Douane (TPD) form which eventually gets printed out.

Next is money changing. This seems to be a problem at Taleb Larbi. As Yves found, they claim not to have enough in the office and there’s no bank at Taleb. In our case I got 400FF’s worth but the others got only enough to buy insurance (about 200FF) and the last lot had none. It then transpired that the guy in the insurance office (‘SAA’) took FF anyway. This is probably best paid out of your declared FFs, not your stash.

While I was waiting, taxis drivers just past the gates offered to buy clothes and exchange black market money, offering around 10-20% more. If you’ve arrived low on fuel and you have insufficient official dinars you may need to buy some black to move on. The fuel station is just down the road. We left Taleb round 3pm.

At some stage of course you must buy official dinars (it looks good on your declaration – keep receipts). We did this at the bank in Debila, the first main town after the border. It had just closed but the guy saw the ten of us and generously opened up again to do a quick change for us all.

Stone throwing kids

I’d read about the stone throwing villages west of the border on sahara.info.ch and sadly the reports were true. For once I was spared but the Discovery at the back got hit hard two or three times. Most of the kids wave but the ones who throw mean business as the heavy dents in the Discovery’s door proved. Had it gone through a window and struck the driver it would have been nasty. The last car is usually the target because there are no following cars to see who throws it, I suppose.

Unless you’re lucky, trying to catch the culprits or going to the police is a waste of time, but I guess that some irate tourist with a smashed window will do this some day soon and hopefully something will be done. On the ferry back I spotted a tourist car with a smashed window and heard of serious stone throwing in Kufra (Libya) and even at a local guide’s car in Dakhla (Egypt).

Laisser Passer and Gassi Touil convoy

We spent the first night in Algeria in the sands just south of Touggourt (although there is the Hotel Oasis in town somewhere).

At Square Bresson (just a junction) there are masses of sand roses laid out for display. Soon after, at a checkpoint just before Hassi Messaoud we had to get our permit for the south – about an hour of writing everyone’s details down in Arabic. But the laisser passer was only requested a couple of times in the Gassi Touil over the next day or two. No one bothered with it or even passport checks south of the oil zone.

We got caught up in a military escort at the Gassi Touil checkpoint, halfway between Hassi Messaoud and Hassi bel Guebbour (HbG). It meant waiting until 3pm (or 9am) for a 100 km drive to another checkpoint or base and continuing the next morning at 10am to HbG. We were told only ‘Toyotas and fuel tankers’ must join the convoy as these have been preyed on by bandits (from ‘Mali’ or course). But while waiting plenty of Toyotas and tankers went through so who knows… It delayed us by about half a day so schedule this into your plans or go via Deb Deb (Libyan border route).

Unlike many other towns in Algeria, HbG is still the one-camel truckstop it was ten years ago. Just a couple of cafes and a checkpoint. There was no problem with us heading down to Bordj Omar Driss (stopping for a wash at the warm spring 2km from Hassi).

On the piste at last

We left the tarmac at Quatre Chemins (checkpoint) and headed west along the very rough Amguid track, leaving it early down a sandy ramp towards the Gara Khanfoussa dune crossing and the 410-km-run (fuel to fuel) to Illizi. Once you find the entry point for GK and the old piste rising up over the dunes, with 1.5 bar the crossing is very easy (in our case perhaps helped by the recent heavy rains). There are many recent tracks winding their way over the easiest dunes and by following them you encounter no dangerous crests to speak of. After the first section you drive into the Gara Khan clearing and then keep on the west side to head directly south (a mistake we made when I did it ten years ago). Beware of sharp ‘crests’ as you drive back onto the old orange built-up piste on the way out of the dunes.

Once in the valley we passed Tabelbalet well (good water at 6m), tried to drive along the dunes on the east side (as advised because of flood damage on the track). But the dune banks were tiresome and we found the track OK. Next day we passed Ain el Hadjadj (ruins, good water) and followed the track right to the point where you cross the strip of dunes at around N26 38′. It helps to walk these first to work out the way through. Once you know which way to go it can be done in 10 minutes. No one got stuck except me!

From here east to Illizi is one of the most beautiful pistes in these parts, with the rosey dunes of the Erg Issaouane glowing to the north, a clear track and plenty of nomads camelling around. Just when you think it’s all over there is a steep sand slope to ascend about an hour from Illizi (waiting for GPS info). You’ll need to degonflate to get up this one – watch out for the rocks on top.

If you’re heading south via HbG then this piste certainly beats the tarmac to Illizi.

Illizi to Djanet

In Illizi we were lucky enough to get fuel, water, bread and even a restaurant lunch (250d each) without getting hauled in to the police and army as Yves reports on point 11. If they don’t ask don’t offer. From here it was tarmac all the way to Djanet, covering in two hours what took a gruelling day a decade ago. We visited the village of Iherir (basic camping at the north end of the settlement – introduce yourself to the teacher, Ibrahim Kadri). The road to this canyon oasis is much improved (30 mins) and may well be tarmaced by next year.

We did the Tuareg tea thing with Ibrahim that evening and next morning went for a walk with a guide up the valley to see the guelta, gardens, rock art and the old Turkish fort (700D for our group of ten). We also left some old clothes with Ibrahim for the villagers.

Down the road, Dider looks as lovely a lunch/camp spot as ever and there is now fuel at what has become the small refugee town of Bordj el Haouas (checkpoint). You could do Illizi – Djanet in a day.

Djanet

The new tarmac makes a lovely drive into Djanet – now you can look around at the countryside instead of the piste. There was no checkpoint on entering Djanet (though there were frequent night time roadblocks) or need to get permits for fuel, as before. We stayed at the only place in town: Hotel Zeribas (250d to camp per person, cars free, basic rooms around 500d) right in the town centre next to the post office. I was told the place was dump a year ago but it looked fine to me, with hot water, plenty of shade and good security. They’ll try and rope you in for a cous-cous meal in their restaurant, nothing special and overpriced at 500d pp. There are restaurants just out the door. The Hotel Tenere, miles south out of town, appeared to be closed or waiting for the Xmas charters. There’s a shadeless campsite near it, but it looked deserted too.

Guided excursion to the Tadrart

I organised a guide with Agence Essendilene for a tour of the Tadrart (SE of Djanet) and Alidemma arch. We were advised that my proposed route would take much longer than planned (although a friend did the full tour a year ago in 4 days). It was a guide’s ploy to get more days out of us (a new one me!). In the end we settled on 4 days, Tadrart only at 1200FF a day. We also paid 25d per person per day in the national park at the park office/museum in town. Once we got to the Tadrart it was clear the guides were stringing out the route to fill 4 days, crawling along at times at 10kph. We would have rather driven at a normal speeds and camped early to enjoy time out of the cars, which we later did.

I was looking forward to the Tadrart but to be honest I was disappointed. The sandy drive out towards Mt Tiska and following oueds south of the corrugated Ghat piste was great (and driven at normal speeds). But Oued In Djerane was very dusty and for the price I paid, the region did not quite have the edge over the very similar (and contiguous) Akakus in Libya. Of course, unlike the Akakus, the Tadrart has zero tourists. The ochre dunes at T-in Merzouga were the highlight. Our guides Ahmed and Slimane were a good bunch of guys and, with an email contact in Germany, I may hire them again directly, at a more normal price.

Unfortunately one of our group was injured an accident on Day 3 and we had to return directly to Djanet. Amazingly the Defender nearly made it back in 2WD, at which point the severely traumatised transmission finally gave up the ghost. The doctors at Djanet hospital were extremely helpful and confidence inspiring. The injured driver eventually flew back to the UK via Algiers, with the aid of his travel insurance and looks like making a full recovery. The car was a write-off. There are no modern Land Rovers in Algeria, only ancient Series IIIs. Recovery to the coast was not worthwhile and so it had its contents and components ‘optimised’ and was left with the Customs. Vehicles cannot be sold in Algeria. The Douane huffed and puffed a bit about parts missing from their new ‘present’ (what a nerve!), but once they realise it’s more wrecked than it looks they won’t be quite so thrilled.

Telephoning from Djanet

Trying to organise the repatriation exposed the near impossibility of telephoning out of Djanet, even just to the next town. The problem seems to be many new private telephones but just one inadequate satellite/radio dish. I was on the verge of driving 400km to Illizi (linked by land lines and therefore much more reliable), but had one more go at sundown – Ramadan eating time when all goes quite. However the insurance never managed to call back. So despite what I say in the book on p.276, a sat phone would have been useful here. (incidentally the hypothetically described Medevac procedure on the opposite page – outlined to me by a Loss Assessor – proved to be pretty accurate. Getting to a town/phone/hospital is the key. However, the insurance insist on proof that the claimant cannot continue the tour as well as a doctor’s report to prove they are safe to fly. This is what cost us days and why we gave up in Djanet – they could not get through).

Not surprisingly, GSM mobiles don’t work in Algeria (they do in Tunisia), but I was told that next year they will, even down in the south.

Route A2 to the Hoggar

With the injured driver slowly on the mend, two cars from the group offered to help assist his recovery to the UK while I continued with the VX and Discovery to the Hoggar. We managed to get diesel at Bordj el Haouas (Ramadan shuts everything down at 3pm) and then headed south along the chain of mountains that end in the landmark of Tazat (an interesting area to explore for another time I think). Mistakenly thinking we needed to move fast to catch up for lost time, we drove from Tazat almost to Assekrem in a long 400km-day. As described in the book the junction at ‘Borne’ is still confusing and we dithered around a bit before heading resolutely SSW over confusing tracks with another lost G-Wagen crossing out bows. Soon we found the crucial cairns and balises that lead into the valleys all the way to Serenout fort (quick passport check) and on past Telertheba. Despite what it says on p.397, the southern route from Serenout (as marked on the IGN) seems to be the main way and is a lovely drive with the 2455m Telertheba looming ever larger up ahead. The sandy sections mentioned on A2 in the book didn’t cause any problems – one wonders if a flat sandy track improves with little passing traffic.

There is diesel only at Ideles from where a corrugated track leads to Hirhafok. At Hirhafok we turned south for Assekrem.

I knew this piste would be washed-out, but the closer we got to Assekrem the worse it got, to the point where one could barely believe anything less tha a Unimog could drive it. The last 50kms took 4 hours in Low Range with extremely slow and rocky going up to and beyond the Tin Teratimt Pass. From here on it was so damaged one could hardly work out the original track among the many deviations.

We had Assekrem to ourselves but there is a whole menu of prices there: parking, parking more than an hour, breathing, etc. The ‘chatty’ guy in charge tried to charge us for camping, too… To be fair it can’t be cheap to run the place and the lovely lodge is well worth an overnight (even at nearly 1000ds demi-pension) so you can see dawn over the plugs.

Tefedest East

We returned down the track from hell (not so bad this time but I doubt any local would use it), fuelled up at Ideles, getting caught up with the bored police opposite the pumps for a tiresome “what’s your job, address, mother and father’s name” check. Backtracking, the turn off north for Mertoutek is clear if you’re looking for it and the track unrolls clearly, passing through some lovely spots to a turn-off at a big green sign a few kilometres before Mertoutek (as marked on the TPC). From here twin ruts lead north to Dehine and continue all the way along the east flank of the Tefedest range past the distinctive peak of Garet el Djenoun at its northern end.

The Discovery’s rear radius arm broke, probably as a result of the exertions of the previous day, and with me taking on the car’s fuel and water payload, my 61’s rear main spring also snapped a day later. The flat helper springs had also snapped off I discovered, but the second spring sort of winds round the mount so I could carry on without much problem. The other rear main spring has since broken. I never rated these two-year-old Ironman rear springs for heavy load carrying (front are fine) and will be getting some heavy-duty OMEs.

We had a day off by Garet and then continued north along the west of the Amguid erg, through the pass and northwest back to HbG, a clear if corrugated track marked with oil drums much of the way.

This is a lovely way back north, easy to follow with no GPS needed – 710kms from Ideles to HbG. The last 150km are a flat and dull and after the final rise, the eastbound track back to 4 Chemins is very rough but can be avoided by going via Bordj Omar Driss, I’m told.

Back north

We just about managed to wangle our way out of a return convoy north, and continued slowly with the four-wheel steering Discovery all the way from Gassi Touil to Nefta in one very long day. Getting out of Algeria took two hours with no searches or money checks (the same as years ago), just very slow-witted officials at Taleb. At Haouza they asked for Green Card insurance (a first) so those without had to buy a week’s worth for 10Td. After 1200km of hairy handling with just a winch cable and a chain holding the axle in place, the Discovery got its radius arm welded in Nefta and we met up with the rest of the group at La Goulette for the ferry back to Genoa.

Weather

Following the severe October rains west of Illizi, we were blessed with no daytime wind and amazing clarity the like of which I’ve never seen in the Sahara. You just could not help staring in amazement at the crisp profiles of the ergs and the mountains. Temperatures were mild too, even at 1800m in the Hoggar it only dropped to 7C.

We also saw plenty of dorcas gazelles which I’d never noticed before and of course thriving Tuareg nomad activity here and there which, along with the famously diverse landscape, is what makes Algeria so special.

Conclusion

While it was a shame not to be able to complete the tour with the whole group, Algeria is as good as I remembered: the desert has plenty of tracks, as easy or as hard as you want, and all without excessive hassles with guides or permits. I would not choose to visit the Tadrart again, instead I’d rather explore places like Erg Tifernine and Tihodaine, and the Tazat and Tefedest mountains, as well as more southern routes linking Djanet with Tam. This will be the basis of my 2001 tour.

The most tiresome element is, as always, border stuff on the Carthage and at Taleb, but then if it was easy everyone would go here! I met Gerhard Gottler on the ferry back, updating an old Algerian guide and preparing a new Sahara-wide guide (in German). He agreed the southeast of Algeria is the ‘fillet mignon’ of the Sahara. With one easily obtained visa you get a lot for your money in Algeria, and you can always spice things up by pushing further south to the Tenere in Niger.

While the north and the far west may be risky, security in the southeast was never an issue. The gendarmes bombing around in their green Land Cruisers (a cut above the average army and police) inspired confidence and greeted us warmly, as did everyone.

Tony van Gastel – 2002

Long associated with mysterious beauty, Islamic learning and enormous wealth, Timbuctu the Forbidden City has always fascinated outsiders. Early European travellers were determined to reach it, but many did not make it. Between the late 16th century and the middle of the 18th century at least 43 travellers made an attempt to reach it, of whom just four succeeded. The first European, Gordon Laing, who reached Timbuctu in 1826, never returned. Rene Caillie reached Timbuctu in 1828 and came back to tell his story.

Timbuctu fascinated all of us and we were set to reach it. The city has achieved a legendary reputation and ‘Going to Timbuctu’ is similar to going to the end of the world, one of the most desolate places on earth.

Even today it is still a challenge to get there. Roads are said to be non-existent; Timbuctu can hardly be reached by land. Our objective was to get to Timbuctu without the help of a tourist guide.

We were with two Dutch families in two strong 4-wheel drive vehicles: a Toyota Land Cruiser and a Nissan Patrol.

Furthermore, some spare parts should be taken along. It is difficult to decide which parts to take. We had spare fan belts for both cars, break/clutch fluid and extra oil. For the Toyota, I decided to take spare shock absorbers, because on a previous trip to Mali (November 1997), we had ruined both rear shock absorbers.

Travel documents/car papers: For a Ghana-registered car, in addition to a Ghana driving licence and car insurance, the following documents are required:

International driving licence;

International Certificate for Motor Vehicles (Carte grise);

ECOWAS insurance, from the Ghana insurance company possible for a period as short as 14 days (Cedis 25,000 = 10 US$);

Multiple entry visa for Burkina Faso, easily obtained in Accra (CFA 15,000 = 30 US$); and

Visa for Mali, also easy to get in Accra (US$ 40).

How to sleep?: We had fitted a roof rack on the car over which a mosquito net could be arranged. The second couple had arranged and packed the car in such a way that they could easily sleep inside.

Enough fuel?: Both cars were running on diesel. The Toyota had, in addition to its main 95-litres tank, a second 55 litres tank. We would carry along two extra jerricans, which we would fill up in Segou. After Segou it is not sure if fuel will be available. The Nissan had a regular 90-litres tank and an additional 110 litres in jerricans.

Driving through sand: We had a locally-made set of sand ladders and carried a shovel along. Since one of the secrets is to lower the tyre pressure when driving through deep and soft sand, we also had purchased a small compressor to re-inflate the tyres. Lastly, we carried a long towing rope to be able to pull a car out off a sandy patch.

Navigation: To drive from Accra to Segou the only tool really needed is a good road map. We took the following maps along:

Ghana: the Shell map, available from book shops in Ghana,

Burkina Faso: the IGN (country) map 1:1,000,000,

Mali: the IGN country map 1:2,000,000, and

West Africa: the Michelin North West Africa map (1:4,000,000).

Passing through larger cities such as Kumasi, Ouagadougou and Bobo Dioulasso could be difficult, but the West Africa Rough Guide and the Lonely Planet Travel Survival Kit both provide good city plans.

The main problem is to get from Niono to Timbuctu and back. The IGN 1:200,000 maps are extremely useful, but outdated. Furthermore, tracks in the desert do change from year to year and from season to season, so that one can never completely rely on these maps. However, reaching Timbuctu without hiring a tourist guide (one of our objectives) requires a complete set of these IGN 1:200,000 maps.

Global Positioning System: The most useful piece of navigation equipment is a GPS. It is based on 24 satellites orbiting the earth at a very high altitude. A GPS serves as an extremely powerful compass.

In preparation for the trip, we had entered the complete route (the best track seen on the 1:200,000 maps) from Nampala – via Lere, Tonka and Goundam – to Timbuctu in the GPS. Approximately every 5 to 20 km a waypoint had been selected and the co-ordinates (longitude and latitude) entered in routes.

During the trip the GPS was mounted on the dashboard of the car and it permanently determined the location where we were on the map.

Water and Food: When travelling out into the bush plenty of water and enough food should be carried. The temperature during the day is extremely high (high forties) and a human being will at least need 6 litres of water per day (if not more). Furthermore, water is required for washing and cooking. We had a capacity of 120 litres water (60 litres in each car). In addition, we would buy (if available) bottled mineral water.

The food supply consisted of rice, spaghetti, soup, baked beans, corned beef, tinned fish and sausages, cream crackers, etc. Furthermore, coffee, sugar, milk powder, and tea are essential.

Day 1: Saturday April 25, 1998; Accra – Bolgatanga; 850 km

Over tarred roads in reasonable condition, the first day brought us to Bolgatanga 850 km from Accra, where we arrived at 5:45 pm, almost 12 hours after leaving Accra. Accommodation in Bolgatanga was at the guesthouse of the Presbyterian Primary Health Care Centre.

Coffee break, lunch break, as well as an afternoon rest stop, were all taken along the road, searching for a quiet place and some shade. In fact, we would take off as early as possible and also have breakfast at the roadside.

Day 2: Sunday April 26; Bolgatanga – Bobo Dioulasso, 560 km

On the second day we departed at 6:00 am and travelled, again over tarred roads in good condition, from Bolgatanga in Ghana, via Ouagadougou, to Bobo Dioulasso in Burkina Faso; a total of 560 km which we covered in 10.5 hrs. Approximately 45 km after Bolgatanga (on an excellent road), the Ghana departure formalities had to be carried out in the border village of Paga, which included:

Health control. It is totally unclear and ridiculous why – when leaving Ghana – the yellow fever vaccination has to be valid. The health people also had to write all the passports in a large book.

Passport control. For each passport a disembarkation card had to be filled out, after which the Chief Officer stamped the passports.

Registration of the vehicle. The international driving licence and the ECOWAS insurance had to be registered. You would expect them to look at the Ghana national driving licence and national insurance. Anyhow, it did not take much time.

Custom inspection of the vehicle. An officer had to inspect the contents of the car.

Immediately after leaving the Ghana border, the Burkina Faso passport control (visa control), as well as the control of the car papers (carte grise, international driving licence and ECOWAS insurance) took place. A fee of CFA 1000 per vehicle was charged for “stationnement”.

The whole procedure took less than 45 minutes. Both Ghana and Burkina authorities were correct and friendly, except for the usual attempt to extort a little bribe (called dash in Ghana and cadeau in Burkina) when the custom officer was inspecting the vehicle.

Approximately 18 km further, in the village of Po, the last official formality to enter Burkina Faso took place, i.e. buying a Laisser-Passer (CFA 5000). This important document allows the import and export of the car free of charge for the period of the validity of the Laisser-Passer. It is similar to the Carnet the Passage, which travellers coming from Europe will usually carry.

Along the stretch Po-Ouagadougou, a lot of photogenic villages with huts and (hopefully fully filled) grain stores can be seen. Since it was the end of the dry season, huts were freshly thatched and some walls were newly decorated with geometric patterns. In general, the vegetation is becoming less and less. This is sorghum/millet country, but crops had been harvested some months earlier. Many Eucalyptus and Neem trees are growing along the road. Furthermore, we saw several water pumps and water ponds.

Breakfast was taken at 9:00 am somewhere along the excellent tarred road between Po and Ouagadougou. Coffee later in the patisserie La Bonbonniere in Ouagadougou. The patisseries in Ouaga are highly recommended. We slept in Bobo Diaoulasso at the compound of Casa Africa on the roof rack of the car.

Day 3: Monday April 27; Bobo Dioulasso – Niono; 420 km

That day we wanted to reach Segou. We departed from Bobo at 7:15 am and the city plan in the Lonely Planet Guide helped us to leave the city. Via Bama (big irrigation scheme) and

Dande to Fo (93 km from Bobo), where you surrender the Laisser-Passer to the authorities. This office is rather easy to miss, since there is no clear indication where to stop. After Fo you continue for another 25 km to Faramana, where the rest of the Burkina Faso exit formalities have to be completed:

In the second office:

Finally, just before Kouri (a number of kilometres after Sona), the Laisser-Passer for Mali (CFA 2000) has to be purchased.

During a previous visit to Mali they tried to cheat us by having us pay an additional exit fee, since we departed on a holiday (Sunday); this time we were treated correctly, if slowly. Via Kouri, Koutiala and Bla we travelled to Segou over usually good roads (under construction here and there; potholes before crossing the Bani river). We arrived in Segou at 2:00 pm; seven hours after departure from Bobo Dioulasso (310 km behind us).

In Segou we did some shopping (a.o. boxes of mineral water). We filled all water jerrycans. We filled the cars up with fuel and -this time- also the two spare jerrycans. Two hundred litres would bring us to Timbuctu (700 km away) and -if needed- back to the tarred road in Douentza, provided the fuel consumption would not exceed 5 km to a litre.

Segou is the second largest city in Mali (after Bamako) and we paid a visit to the waterfront, where most of Segous activities are taking place. Pirogues and pinasses are loaded for trips up and down the Niger. It seems that such boats are never full; people of all ages, bicycles, motor bikes, goats, large bags with all kind of stuff and more people, bicycles, motor bikes and goats are loaded again and again. Finally, when you start thinking it may sink, it takes off. In the river, people are doing the laundry, bathing and relieving themselves. Not a place to swim, it must be a serious health risk. On the banks of the Niger a lively trade is going on and women in colourful clothes are moving around.

Since it was still early we decided not to stay in Segou but push on to Niono; approximately 110 km north of Segou. This road, again tarred and in good condition, follows the Niger up to Markala, where we crossed the river on a dam. The landscape is not changing much and is mainly rain-fed agriculture, sorghum and millet, with the occasional tree. After Markala the road gets worse and we drove through a large irrigation scheme, where sugarcane and rice are grown.

In Niono, where we arrived at 5:20 pm we checked out the Campement (the local government establishment in town) and decided to spend the night in the air-conditioned rooms (CFA 15,000 – 17,500). We enjoyed the cold beer and soft drinks as well as a dinner of fish, beef or chicken with either rice or chips. There were quite a lot of mosquitoes in and around the Campement, which bothered us a little, but all in all an enjoyable stay.

In Niono, there are three fuel stations, of which one had a good supply. Of course we filled up our fuel tanks to the brim.

Day 4: Tuesday April 28; Niono – Sanbani; 300 km

To Nampala (154 km from Niono)

We left Niono at 6:10 am for the first leg to Timbuctu. People had mentioned that it would be possible in one (long) day, but only if you knew the road; something we certainly did not. We would see how far we would reach and were prepared to camp out in the desert.

Immediately out of Niono the dirt road begins. The road runs north along a main irrigation channel and at both sides of the road rice and some maize is grown. The road is firm, but rather dusty. We did not use the A/C of the car, because it was rather cool. Later on we decided not to use the A/C to save fuel, because fuel consumption is considerably higher when running the A/C. Along the road were many small villages, which reminded us of the Nile delta in Egypt.

After 33 km the road becomes poor and we drove along a minor irrigation channel. The surface of the road is sometimes very loose; very fine dust completely covers the back and the sides of the cars when driving through. Approximately 81 km after Niono (two hours drive), the irrigation channel ends and the landscape becomes drier and drier; very bushy indeed.

We were heading almost east and getting closer to Nampala. The road has deep potholes and gullies and the going is sometimes very slow. We often had to leave the main track, searching for a better one. During the rainy season this road must be very difficult to negotiate; cars and lorries will seriously get stuck during that period. The track then turned more and more north and the GPS indicated that we were heading straight towards Nampala. The last 30 km was on a firm dirt road (sometimes a bit sandy) with a lot of corrugation; keeping up speed (50-60 km/hr) is the best medicine for corrugation, but watch out for gullies and potholes.

Five hours after leaving Niono, we reached Nampala. The average speed had been approximately 30 km/hr (including a short breakfast stop). We had seen a lot of villages, people and taxis on the first 60 km, but the last 100 km were completely desolated; no villages, no cars, no human beings, only a few goats.

Nampala: In Nampala (not much more than a few huts) there was fuel (guidebooks indicate there usually is not) and they filled up our tanks from a drum .We discussed the road to Lere and were told that it was no problem at all. They pointed out which direction to go (was there a track?).

To Lere (95 km from Nampala)

Based on the track indicated on the IGN 1:200,000 (Nampala) map, the co-ordinates of 16 waypoints between Nampala and Lere had been entered in the GPS.

The first 10 km were somewhat sandy, but further on were long stretches of firm surface, where we could drive 80 km/hr. We did not meet any cars, only very few people (inhabitants of the few hut villages) and goats (who are able to survive in almost any environment). The landscape is very dry and bushy; vegetation very sparse.

On this stretch we learnt to appreciate the GPS. It gave us peace of mind; we never worried that we were on the wrong track. The compass-page of the GPS always indicated the direction to go, as well as the distance to the next waypoint. When we reached a junction (and there are many) we usually let the GPS decide which track to take. Once we ended up on a secondary track, which ended in the middle of nowhere, but the compass-page of the GPS brought us again straight to the next waypoint.

We also learnt that the majority of tracks, indicated on the 1:200,000 maps, do not exist. On the other hand, there are many other tracks, often just a footpath.

At 2:20 pm (8 hours after leaving Niono; average speed 40 km/hr) we reached Lere. The temperature was 43oC and relative humidity approximately 5%.

Lere is a small village with a few very small shops and a market place. It was a surprise to hear that there was fuel, but we had just filled up in Nampala. We had to stop at the police to register the car and at customs, who recorded the Laisser-Passer.

To Niafounke

According to guidebooks the route from Lere to Niafounke is difficult and you may easily get lost. A guide is, therefore, recommended. We decided to try it by ourselves. The co-ordinates of more than 30 waypoints of the route indicated on the 1:200,00 map (Sa) had been entered (in Accra) in the GPS. With the experience of the previous day, when we drove from waypoint to waypoint, it could not be too difficult. The distance (Lere-Niafounke) indicated on the 1:2,000,000 Mali map was 214 km. After asking a few people in Lere the direction we took off to Niafounke.

Immediately after leaving the village, the track headed into a total different direction (the GPS indicated we should go north, while we were clearly heading south).

Soon it appeared that we were following a track along the south shore of Lake Tanda (it had no water and did not look like a lake) on the 1:200,000 map (Sa). Via the very small village of Tirna, we drove to Diartou. Just after Tirna, we knew that we were on the correct track, because a signpost indicated the direction to Niafounke.

The track continued South of the next lake (Lake Kabara). We camped approximately 5 km east of the village of Sanbani. All in all, we had only driven 70 km since Lere (including all detours); it was 5:00 pm and still hot (high thirties).

It turned out to be one of the best nights; nobody bothered us, the temperature dropped and early in the morning it was only 23.5oC. We needed our sleeping bags.

Day 5: Wednesday April 29: Sanbani – Timbuktu; 250 km

To Niafounke (65 km from Sanbani)

We had an excellent night and left after breakfast our one-million star hotel. We kept following the main track, which headed east straight into the direction of Niafounke. We drove along the northern shores of a number of small lakes. Some water was still present, but in the rainy season these must be large lakes or gullies. After Dabi, the road (over a dyke) is going straight to Niafounke, which is situated on the Niger. We arrived in Niafounke at 09:00 am, approximately 2 hours after departure from our desert camp. The distance was only 65 km, but we spent some time along the lake and had a second breakfast along the road.

In conclusion, the track Lere to Niafounke is not bad. However, it is rather easy to loose your way. Do not follow the track indicated on the 1:200,000 map (Sa); it either does not exist or is not used this time of the year. It is also clear that there is no fixed track to Niafounke, it varies depending on the season. In the rainy season the track probably follows a more northerly course, while at the end of the dry season it follows the shores of the lakes. The present route is an advantage in terms of distance; the route indicated on the IGN Mali 1:2,000,000 map is 214 km, while this one is only 120 km.

Niafounke

Niafounke is a pleasant town located on the banks of the Niger. It has a Campement. Single rooms are available for 6,500 CFA and doubles for 10,000 CFA; clean rooms with fan (no A/C), toilet, shower and running water. In the Campement we had cold drinks, bought small flat breads and talked to the captain of the Niafounke ferry. He was slightly drunk, but argued that the best way to Mopti was crossing the Niger with him; another two hours would then bring us to Mopti. People claimed there was fuel in Niafounke. We discussed the road to Tonka and it appeared that there was a short direct route to Tonka (35 km) and a much longer one.

To Tonka (42 km from Niafounke)

We decided to take the shorter one and departed from Niafounke at 10:00 am. The track runs initially along the Niger. Just before the irrigation scheme we turned left into a more northerly direction (this junction is not easily recognised). Again the track out of Niafounke can not be found on the IGN 1:200,000 maps (Niafounke and Tombouctu-Ouest). However, in the small village of Temba (31 km after Niafounke) we joined the track on the 1:200,000 map (Timbouctou-Ouest) and reached Tonka at approximately 11:10 am (1 hour after departure from Niafounke; the distance being 42 km). The road was excellent, certainly the last stretch after Temba.

Tonka

Upon entering Tonka, we stopped at a police post to inquire about the road to Goundam. The police officer must have been in a bad mood, because he wanted to give us a ticket for parking the car in the middle of the road. Middle of the road? We had to argue a long time. The nasty officer also told that it was impossible to travel alone to Timbuctu; it was too hot, dangerous and forbidden to travel without guide. Finally, a more senior officer came and asked whether our papers were in order (which they were) and told us we could leave.

Temperature

We drove through the village of Tonka, which is also located on the banks of the Niger. We were lucky to find somebody who could indicate the direction to Goundam; the temperature had reached approximately 47oC.

To Goundam (35 km from Tonka)

A track leading north brought us out of the village and we followed a different track to Goundam from the one indicated on the 1:200,000 (Tombouctou-Ouest) map. The GPS indicated that we were heading towards Goundam.

The real sandy part of the Timbuctu trip started soon after Tonka. We engaged the freewheeling hubs and used almost permanently the 4-wheel drive and occasionally low gear. At times the sand was very deep and only keeping up speed would avoid getting stuck. High sand dunes had to be negotiated and only speed would get you to the top. Occasionally we had to reverse and give it another try or take a different track. There are many parallel tracks and permanently choices have to be made which track to take. Sometimes you are right, sometimes wrong, resulting in not being able to get uphill or getting stuck. This was really the first part of the trip were a 4-wheel drive vehicle was required.

The track follows Lake Fathi and sometimes we were driving on firm underground, which is the bottom of the dried-up lake. The lake, at this time of the year, has little water, but it must be huge during the rainy season. Approximately 7 km before Goundam, we joined the track on the 1:200,000 map (Timbouctou-Ouest) and were again driving from waypoint to waypoint.

We took off from Tonka at 11:30 am and reached Goundam at 12:30 pm. So far, it was one of the most interesting parts of the trip. The desert environment really makes an impression. The landscape is interesting with often Lake Fathi in the background. It was hot (47oC) and the driving tough. Finding a tree for the coffee break not possible.

Goundam

Goundam is an interesting village, but we did not see a soul. You must be crazy to venture outside at midday. We stopped at Place de lIndependence, were an old sign indicated that the distance to Timbuctu was still 77 km. Somebody told us there were two routes to Timbuctu; one being much sandier than the other. We never knew which one we took, but sandy it was!

Out of Goundam there are two other tracks. One leads to Dire, which is on the banks of the Niger. According to information from travellers there is a track from Dire to Timbuctu. The second track out of Goundam goes to Lake Faguibine, approximately 70 km to the north. It is the largest natural lake in West Africa and one of the best places to watch migratory birds. According to guidebooks the track is difficult to find and a Tuareg guide should be hired. The book also indicates that this track definitely requires a 4-wheel drive (low gear). Initially we intended to go to the lake, but decided against it because of time constraints.

To Timbuctu

At 12:30 am we departed from Goundam for the last 90 km to Timbuctu; the temperature was around 46oC. All the way we used the 4-wheel drive and lowered the pressure of the tyres (to approximately 20 PSI). It was sandy and hilly all the way and there were a large number of parallel tracks. We did not really get stuck, since we kept up speed. The route had been entered in the GPS and we followed exactly the same course

The last 4 km from the airport to the centre of Timbuctu is on an excellent tarmac road; the 8 km before has a very firm underground, but before that there is approximately 10-15 km of very deep sand and high sand dunes. With our experience, we had no problems negotiating these and at 3:30 pm we arrived in Timbuctu!

Since Segou (700 km from Timbuctu), we had not used the A/C and really got the taste of the desert; dusty at times, dry (RH 5%), hot during the day (close to 50oC), and cool in the morning (22oC). We all felt, however, that a dry and hot climate is preferred over the Accra climate (less hot, but very humid).

We drove straight to the best hotel in Timbuctu (got stuck in front of the hotel, which is situated on a hill) and had very cold beer and soft drinks. This may have been the best beer we ever had.

Timbuctu, founded about 1100 AD as a seasonal camp by Tuareg nomads, is located on the edge of the Sahara about 13 km north of the Niger river. It was historically important as a post on the Trans-Saharan caravan route. In the 14th century it became a focal point of the gold and salt trade. Merchants from various places, including Moroccan cities, gathered to buy gold and slaves in exchange for Saharan salt and North African cloth and horses.

Regarding accommodation two options are available, a hotel or out in the desert. The best hotel in town is Hotel Azalai, which charges 27,500 CFA for a double. One of the guidebooks indicated that it would be possible to sleep on the roof of the Annex of Hotel Bouctou. They asked 18,000 CFA for a double room, but if we wished we could sleep on the roof. We negotiated and brought the price for the roof down to 4500 CFA per person. We decided to sleep in the open, someway out of Timbuctu. We drove 15-20 km back in the direction of Goundam and found a quiet place where we were not bothered by anybody. In the far distance we could see the city of Timbuctu.

We set up camp and then opened the bottle of white wine, kept to celebrate our arrival in Timbuctu. The temperature of the wine was close to 35 C, but we did enjoy it.

Day 6: Thursday April 30; Timbuctu – Bambara Maounde; 120 km.

We got up early and to celebrate our Queens birthday and National Day inflated red, white, blue and orange balloons, which we attached to the cars aerial. After breakfast we packed the cars and drove again to Timbuctu to visit the town.

The first stop was at the police station, where you have to register (passports and Laisser-Passer), which costs 1000 CFA per passport. The officers are extremely friendly and happy to see some tourists. Very few tourists visit Timbuctu this time of year. The majority arrives by plane or by boat on the Niger during the cooler months.

Registration with police

According to guidebooks you have to register with the police in the following places:

Timbuctu (which we did), Mopti (which we did not), Bandiagara (which we did not either).

Concerning registration, in case you would not do so, it may get you into trouble later. We got our passports stamped, so that we could actually prove back home that we had been in Timbuctu.

We wandered through the narrow alleys of Timbuctu; all houses built of grey-brownish mudbricks. We passed many Koran schools (madrasses). It was very hot (45oC).

The streets in Timbuctu are not tarred and sandy at times. As mentioned, we got stuck in front of the Azalai Hotel and again in front of the Shell petrol station The Shell station appeared to be out of order. However, fuel was available at another station in the centre of town, close to the market. From Segou to Timbuctu we had driven 706 km and used 113.6 litres of fuel; an average of 6.2 km to 1 litre.

We visited the museum (CFA 1000), bought mineral water and post cards before returning to Azalai Hotel. Postcards were written and brought to the postoffice to get them Timbuctu-stamped.

We inquired about the road to Mopti. The information we gathered was that we would have to cross the Niger, then almost straight on to Bambara Maounde and again straight on to Douentza, where the tarred road to Mopti starts. It would be no problem, but they all offered to be our guide, which we politely refused. This route could not be found on any of our maps. In fact the 1:200,000 maps (Tombouctou-Est and Bambara Maounde) did not show any track at all to Bambara Maounde and Douentza.

We departed from Timbuctu at 11:00 am; 15 km on the tarmac brought us to the Niger, where we could not spot any ferry. After driving a few hundred meters east we found the ferry.

Crossing the Niger River

The ferry did not look very reliable, but we had no choice if we wanted to get to the other side of the Niger river. The ferry was at least 20 metre away from the bank out in the water and the ferry ramp was rather steep; luckily the water was not too deep for the cars. The Toyota drove up the ramp, where the muffler of the exhaust hit the edge and got dented. The Nissan with a slightly longer wheelbase and less ground clearance, was not able to get on; the cross-beam of the chassis hitting the edge of the ferry. We off-loaded the jerrycans (100 litres fuel and 60 litres water) and boxes with food, trying to raise the Nissana bit. Without result. Then the ferry people tried to lift the ramp (with the car on it) using the winch, but the cable broke immediately. It took them some time to get it repaired, using our spanners. Also this whole exercise did not help to lift the car onto the ferry.

The ferry should be moved to a better location, but they claimed there was not enough petrol. Petrol was only sufficient to take the ferry to the other side of the river. After paying 5000 CFA to purchase petrol (we did not see them add fuel), the ferry was moved with help of a small outboard engine. This was fitted on a pirogue, which was attached alongside the ferry (The large diesel engine on the ferry must have stopped operating ages ago). It took considerable time and a lot of assistance from people using poles to get the ferry on its way. Very slowly the ferry moved to the new location. This time it worked; the ramp was slightly less steep and the clearance of the Nissan slightly more.

Finally we were on our way to the other side of the Niger. The cost was 8,500 CFA per vehicle and we paid them 10,000 CFA, but they were still not satisfied. Getting off the ferry was not difficult and finally we were on our way to Bambara Maounde at 12.55 am; approximately 1.45 hours after arrival at the ferry.

To Bambara Maounde (95 km from ferry)

We headed straight to Bambara Maounde. The track was again very sandy with a lot of sand dunes. We used permanently 4-wheel drive and tyre pressure was lowered. It did not matter where you are driving; the track is about 500 meter wide. Just select the best, least sandy and hilly track. After 38 km you find an old signpost in the middle of nowhere indicating straight to Bambara and left to Gourma Rharous. We had very few problems; got stuck only twice while going up a sand dune. We did not meet any cars; only two large camel caravans which were moving in the direction of Timbuctu.

The Toyota got its first flat tyre; a large (7 cm) thorn had pushed its way into the inner tube. It was a rather tiring job, changing a tyre midday at a temperature of approximately 45oC. Initially the jack sunk into the sandy underground. We had to get a piece of wood (from the car) before we could lift the car sufficiently high to be able to change the tyre.

We drove along Tin Bedaouin and on to Bambara Maounde, which is a very small village. A dozen kilometres after Bambara at 5:00.pm, we decided to stop for the night; our third night out in the desert. The trip from Timbuctu to the desert camp had taken 8 hours, while the distance was only 120 km; an average of 15 km/hr.

Meanwhile, a caravan of more than 25 camels walked by and the two camel drivers visited us shortly; they got water, bread, and aspirins. It was another sweaty night, unfortunately the temperature did not drop as much as previous nights, due to the fact that the wind had changed. At 9:00 pm it was still 38oC and in the morning at 5:00 am 28oC. The humidity was also considerably higher (approximately 50% in the morning

Day 7: Friday May 1; Bambara Maounde – Douentza (95 km)

At 7:00 am in the morning we left our campsite and headed for Douentza. The co-ordinates of Douentza had been entered in the GPS and all the way we were heading straight to our destination. Again there was no track on the 1:200,000 map (Bambara Maounde). We drove through the Reserve des Elephants; Route Touristic and saw rather fresh (less than 24 hrs old) elephant droppings and spotted an interesting ground bird; the Sudan Bustard.

Fuel Consumption

The first part of the 95 km to Douentza was still very sandy and hilly. The closer to Douentza, the firmer the underground and we were often driving over the dry lake beds. The vegetation becomes slightly denser, but it still remains a clear Sahelian landscape. In the distance an escarpment could be seen and we drove straight to the west tip of those hills. Right behind the hills is Douentza, were we arrived at 9.45 am.

In Douentza we reached the tarmac again (900 km after Segou and 200 km after Timbuctu) and felt that we had achieved our objective, i.e. visiting Timbuctu and returning to the inhabited world.

Tony and Elly van Gastel (2000)

Agadez – Arbre du Tenere – Fachi – Bilma – Dirkou – Seguedine – Oleki – Sara – Chirfa – Djado Djaba – Orida – Enneri Domo – Enneri Blaka – Chirfa – Tassafasset – Arbre Perdu – Grein – Adrar Bous – Temet – Agadez

The Long Haul to Agadez

It is a very long haul from Accra in Ghana to Agadez in Niger, but finally, on October 17, our group of seven in three 4WDs (Toyota Land Cruiser, Nissan Patrol, and Landrover Defender SWB) got there. In Agadez we stayed at the Fantasia camping (highly recommended). Very good potable water. After a few hours, cold (well, lukewarm) beer and soft drinks were even available from the ‘bar’.

We fuelled the cars (CFA 359 per litre); each car had to carry 220 litres; fuel would only be available in Dirkou and Iferouane. Against all advice, we put the 6 jerricans on the roofrack; we would use them as soon as possible. We arranged the compulsory guide from the very reliable ‘Dunes Voyages’ (CFA 21,000 per day); the travel agency had arranged our travel permit. We had dinner in the excellent ‘Le Pilier’ restaurant. Ask for double portions of chips, otherwise you go hungry.

Agadez is a great place to hang around for a few days. It is very comparable to towns like Gao and Timbuktu. Everything is available, fuel and other supplies. The temperature is great this time of the year (low 30s during the day; around 20 at night). People are very friendly.

Crossing the Desert

The first day we did approximately 120 km. Immediately after leaving Agadez, there is a checkpoint, which will only let you proceed if you have a guide and have at least two cars. Particulars of cars and passengers were recorded and the travel permit was carefully studied. Officers are always very friendly. We were travelling through a bushy (very little vegetation) desert, alternating with grassy plains and stony (pulverised lava rock) plains. Usually there is a clear track. We drove along some completely barren cliffs and made a small detour to the Tuiguidit mountain range to visit some rock engravings.

We met two of those amazing trucks, loaded to the maximum, with maybe a hundred people on top and all their belongings. You hardly recognise the lorry; it is just one heap of people, bags, mattresses, and jerrycans. A really great sight! The lorries come from Libya. We saw several others, but none was as beautiful as the first one. We also noted that one lorry was accompanied by an army jeep with machine gun [these were probably West African workers being expelled from Libya].

The day was crowned by seeing a camel caravan on its way to Bilma: 40-50 camels moving very slowly, carrying grass (the feed for their trip). They carry goat cheese, millet and groundnuts to Bilma and come back with salt and dates.

During our second day, we got to the real desert. We had to deflate our tyres (18 PSI, back; 15 PSI, front), long before we reached the famous Arbre du Tenere. We got stuck occasionally but a shovel and a little push did the trick. Initially we still followed a clear track, but when the main track continues NE to Dirkou (via Achegour) you turn off towards Arbre du Tenere, thye track ends. The scenery is great, sandy plains with low dune ridges here and there, occasionally fine gravel. The plains are slightly undulating. At times the piste is marked with balises.

In the afternoon we reached Arbre du Tenere (270km from Agadez), a metal tree and well in the middle of nowhere.

Filling up our water supplies was not easy at Arbre du Tenere. We had no bucket and the water was 43 meters down. We used one of our cooking pots (now famous, because it has seen the well of Arbre du Tenere – very few cooking pots have). We needed all our ropes to get that deep, but managed to fill the jerricans; a very safe feeling in the desert.

Next morning it was sand all the way to Bilma, not a single tree, no track or piste, just choosing a not too sandy path. We drove through a gassi with sand ridges at both sides, sometimes crossing the sandy ridge to go to a parallel gassi. We got stuck every now and then, but usually a little push would do the job. Twice we needed sand ladders and the shovel to get us moving again.

We met more camel caravans, sometimes with hundreds of camels, on their way to either Bilma or Agadez. We wonder how long such beautiful scenes can still be seen.

Just before entering Fachi we met large numbers of camel caravans, which are resting outside Fachi. The Tuaregs are preparing their tea, the camels are resting and feeding, preparing for the next leg of their long trip.

In Fachi (170 km from Arbre du Tenere and 440 km from Agadez) we reported to the gendarmerie and visited the old fort (pay CFA 500 per person to the Chief of the village). We were invited to tea with the chief. Fachi has 2500 inhabitants, a school, a dispensary and a number of mosques. Water is available everywhere from wells (we replenished our stocks). Flour comes from Libya, millet, groundnuts, and wheat from the ‘gardens’ in the Air Mountains. Vegetables and dates are produced in their own gardens.

Next day, we cut through the mountains north of Fachi (stony, be careful with deflated tyres) and on to Bilma. More sand and caravans. Again stuck occasionally when climbing a dune. One looses touch with reality.. We entered Bilma through the site where salt is exploited. Lots of camel caravans are waiting here to take the salt to Agadez. Tuaregs have constructed makeshift huts with water storage (goats hides), plenty of dates and everywhere the kettle is on.