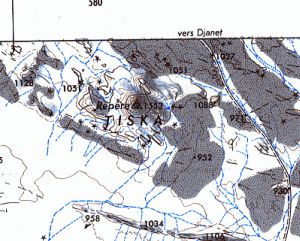

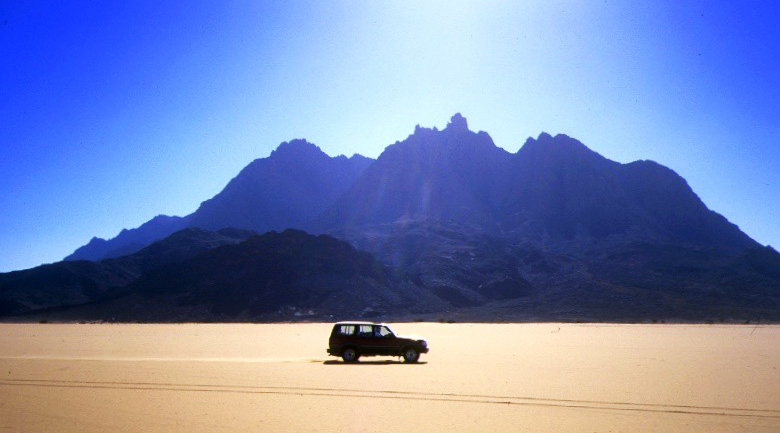

In early 2025 we pulled off a deserted new road and headed across the sands to camp at the foot of Mt Tiska.

I’d been looking forward to this moment for nearly 40 years. My first view of Tiska’s distinctive but distant conical form was from Djanet’s old aerodrome way back in 1987. As I write in Desert Travels:

One evening Philippe, a skinny middle-aged Frenchman who had the habit of walking around the campsite in a saggy pair of Y-fronts, invited us to the airport to inspect his old aeroplane. He was immensely proud of his historic plane, a twin-engined machine from the Golden Age of Aviation. He was keen to point out the enlarged fuel tank which former owner, Lady Vanderbildt or some such, had fitted for a one-hop flight to the States as the war turned on Germany… Philippe started up the engines, but I was far more interested in the view down the runway. From this flat vantage point … south of Djanet you could clearly see the unmistakable conical profile of Mount Tiska … the first and only landmark in the featureless expanse which lead across the Ténéré to Chirfa and ultimately Bilma, nearly 900 kilometres away.

A waterless expanse of flat, soft, sand, this was the route I’d planned to follow with the only partly cognisant Pete: Yamaha Teneres to the Tenere Desert: it could have been adventure biking gold until his breakdown near Illizi had sunk that idea. At that time I knew only a little more than Pete about the realities of remote desert crossings, and it’s no more likely we’d have made it to Bilma than if we’d tried to paddle to Tristan da Cunha in an upturned umbrella.

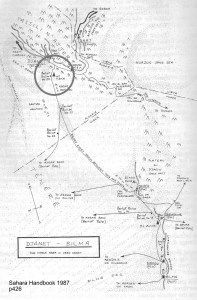

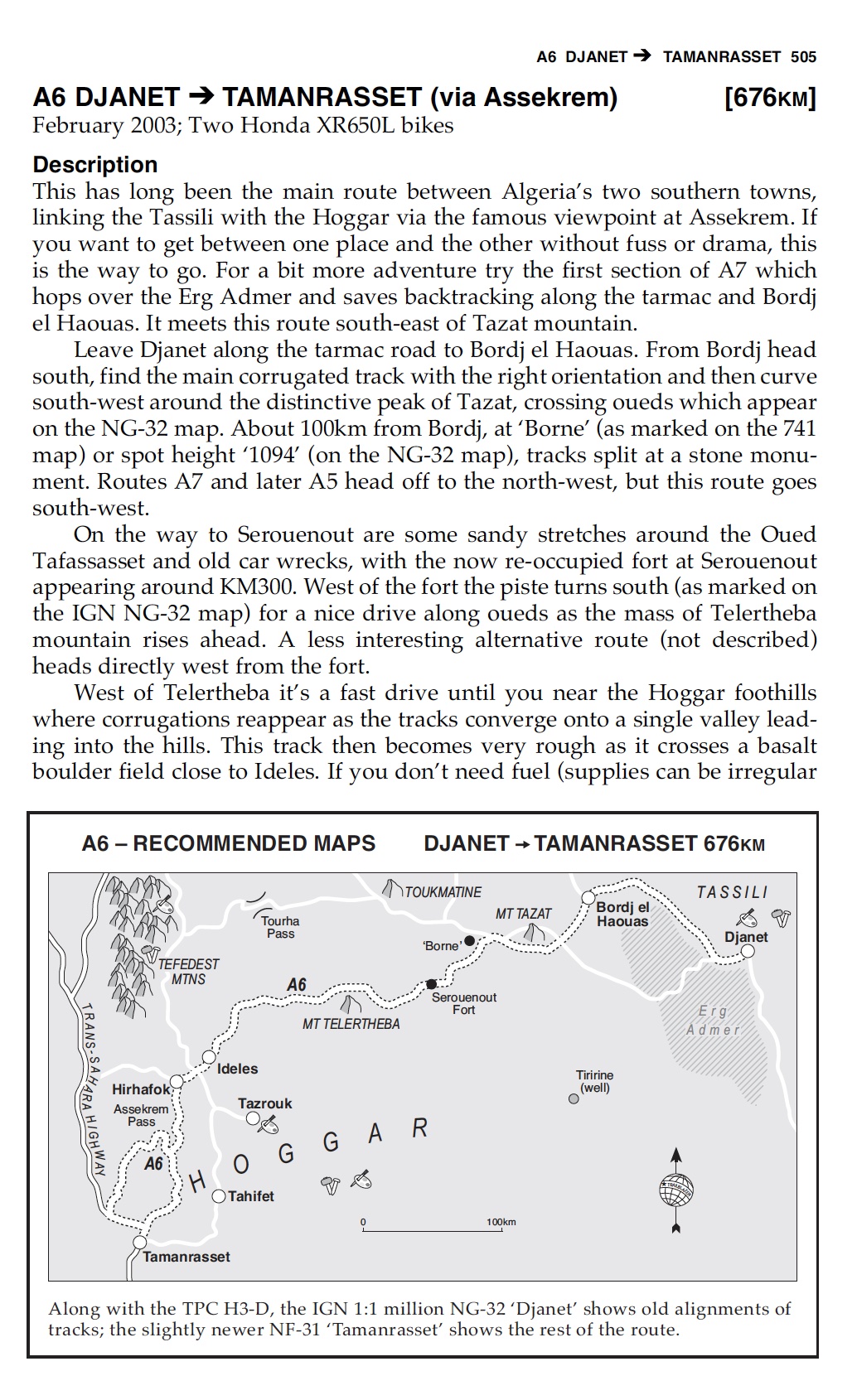

An ancient, pre-GPS landmark, I’d read of Tiska’s significance while leafing back and forth through the original Sahara Handbook (right) in the early 1980s.

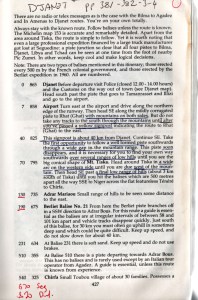

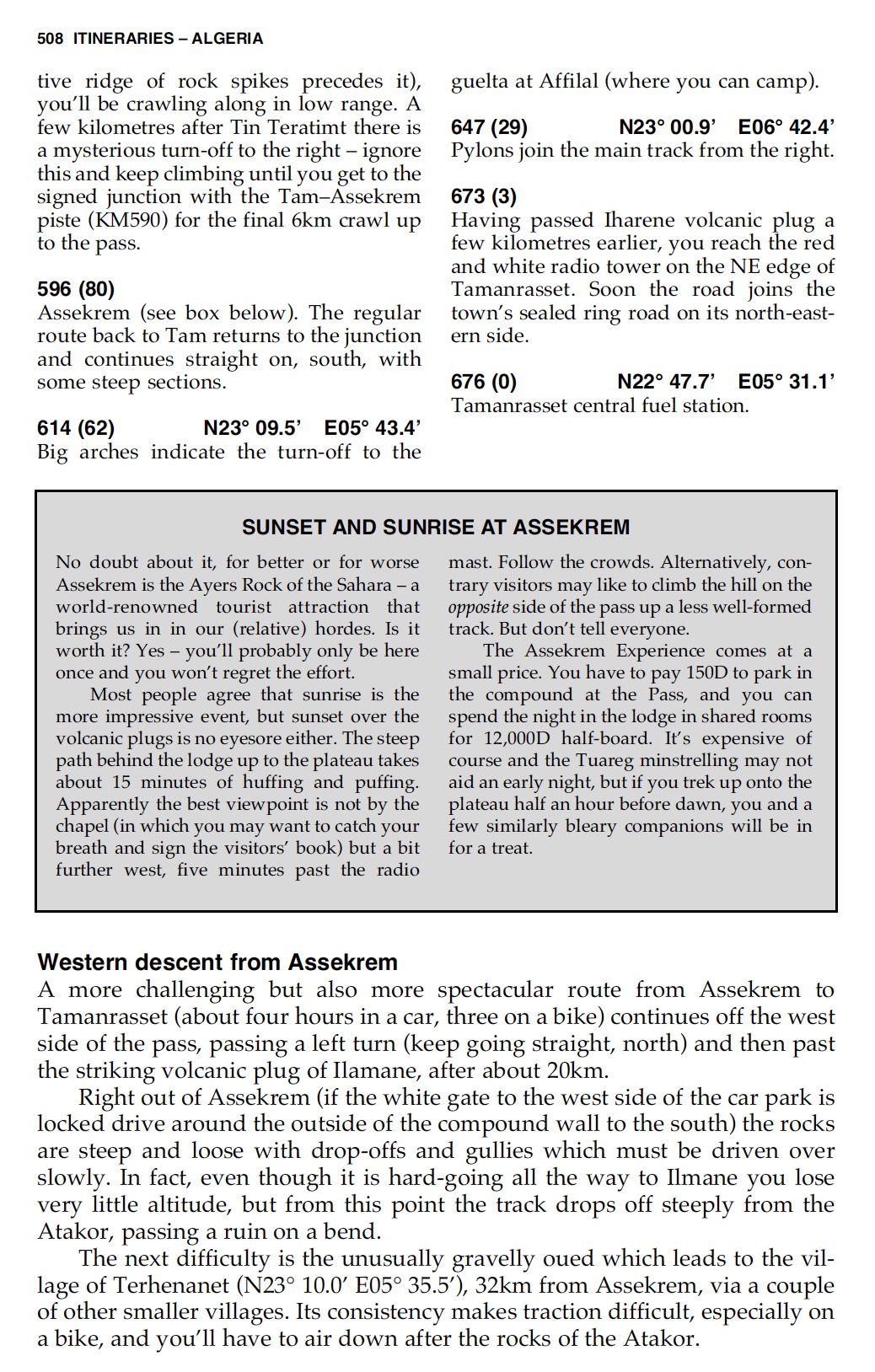

We all have books that leave strong impressions in our early years; the first Sahara Handbook would be high on my list. In it Simon and Jan Glen’s description of ‘Itinerary No. 19: Djanet – Bilma’, reads like call to adventure. You can see my annotated pages notes left, and might marvel at the sparse landmarks including Mt Tiska, with some spaced up to 200km apart. At no less than 865km, this was a serious desert crossing and the Glens did not mince their words.

To run out of fuel or have a major breakdown could be disastrous, as it could entail waiting for perhaps three months for another vehicle to pass and find tours with dehydrated corps lying around. This is no exaggeration, as the seven marked graves near Arbre du Ténéré show… Here your life depends on your vehicle.

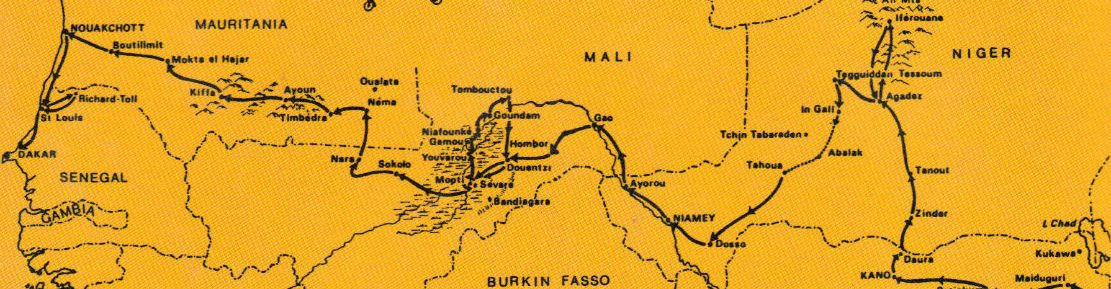

On leaving Djanet for the south, no authorities are interested in how well your vehicle is equipped … [nor] interested in whether you make the journey or not. There are no radio of telex messages as in the case with Bilma to Agadez and In Amenas to Djanet routes. You’re on your own totally.

By the time that was written (final edition three, 1990) the piste to Bilma was little used. It’s said that in 1979 four Land Rovers were lost without trace on this route, and as a result the Algerians closed the crossing and pulled up many of the balises (three-metre-high steel marker posts, below) which the French had erected every 500m from Mt Tiska to Chirfa, the first outpost in Niger and a distance of nearly 600km.

That information was not known to Pete and myself when in 1987 we set off with plans to blithely ride across the Tenere from Djanet to Niger on Yamaha XT600Z Tenere motorcycles. It was a very long way on a bike, but with a balises every half kilometre, it felt doable providing we had visibility and could carry enough fuel and water.

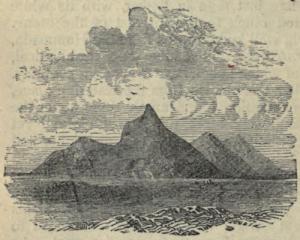

Coming up from Niger, the cone of Mt Tiska (and larger mass of Adrar Mariaou 34km to the south) had long been important landmarks on the caravan route between Ghat and Agadez. In 1860 Heinrich Barth wrote.

August 2 … After a stretch of nine miles, an interesting peak called Mount Tiska, rising to an elevation of about six hundred feet, and surrounded by some smaller cones, formed the conspicuous limit of the rocky ridges. The country became entirely flat and level … and there was nothing to interrupt the monotonous plain but a steep ridge, called Mariaw, at the distance of about five miles to the east [probably Adrar Mariaou; 34km south].

The nature of this desert region is well understood by the nomadic Tuarek or Imóshagh, who regard the Mariaw as the landmark of the open, uninterrupted desert plain, the “ténere;” .

But in 1987 Pete didn’t even make it to Djanet on his Tenere. And soon after I arrived I learned what I now know. Since that aborted crossing, I’ve met others who tackled the route anyway and either got in big trouble in Dirkou in Niger (2001), or got brutally robbed before they even made it to the Niger cut line (2002; probably following a tip off in Djanet). Also in 2002, we came up the balise line from Erg Killian, the Monts Gautier and Berliet Balise 21 (below), but from Mariaou headed directly to Djanet across the very soft sands, bypassing Tiska.

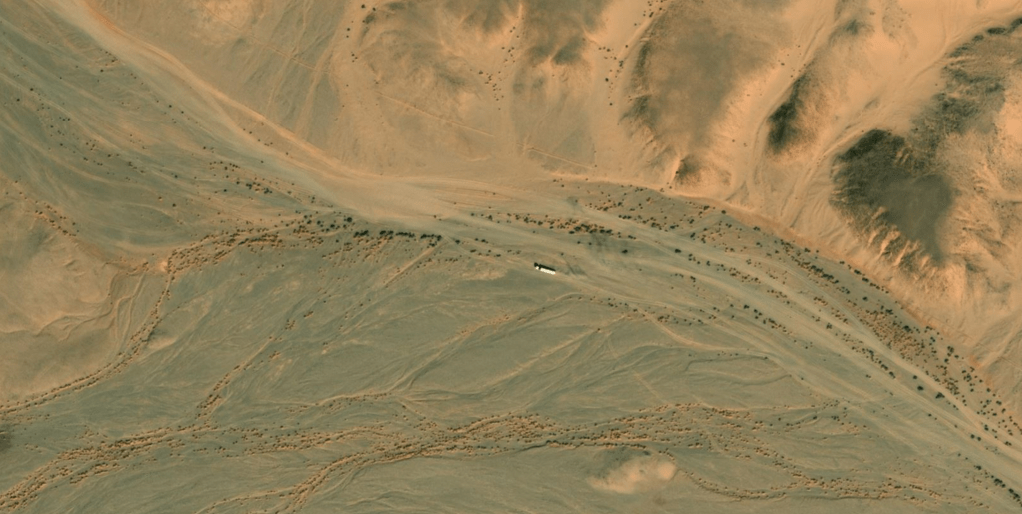

Today, an hour or two from Djanet a tarmac road leads off a roundabout in the middle of nowhere near the famous sign (left) and heads south to pass right by Tiska.

It’s part of a vast network of military roads, remote bases or perhaps migrant camps or prisons, and berms (sand walls) which Algeria has put up in the deep south to control smuggling, migration and jihadist movements.

We pulled into a sheltered dip at the southern edge of the hill (below) and the cook got a fire going. Normally I’d have at least tried to climb to the top but at 500m above the desert floor, Tiska is bigger than it looks, one of the last outliers of the Tassili N’Ajjer before the ocean of sand that is the Tenere runs south to the Kaouar hills behind Bilma and the isolated Termit massif which is already in the Sahel, close to Lake Chad.

It was sure nice to stretch the limbs after being cooped up in the car for days, but it’s these cars which get us to such places. As always walking in the desert, it’s the tiniest things which catch your eye in the void.