Charles Megaw and Jo Butler

Crossing the Sahara desert had long been an ambition of ours. In autumn 2001 we bought a Toyota HJ60 and arranged to take some time off work to do the trip. We wanted to cross the desert north to south, tarmac to tarmac, but didn’t want to do too much backtracking. We settled on attempting to head south through Tunisia and Libya to Agadez in Niger, returning north through Tamanrasset and the Hoggar to Tunis. This route had the advantages of enabling us to fully explore Libya, a country only just opening up to tourism, cross the remote Ténéré and make a return crossing via one of the classic trans-Saharan routes, itself only recently considered safe after the Algerian civil war and Tuareg rebellion. On January 10th 2002 we left home.

Our first challenge was to replace a Michelin XS tyre which blew out on the French autoroute. We found one in Lyon at a considerable discount to what we had paid for new ones in the UK – we should have bought them all in France which would have saved us money and reduced the risks involved in driving on sand tyres on wet winter roads through Europe.

The CTN Ferry, the Carthage, to Tunis was much less eventful and we rolled off at 4pm and spent the first night in Hammamet, 60 kms southeast of Tunis. Hammamet seems a good stopping point for people heading south. We got good value accommodation at the Résidence Hammamet (22 TD a double ~£11), had a large beer at the bar overlooking the Medina followed by a splash-out meal at Les Trois Moutons, reputably rated one of Tunisia’s top dozen restaurants.

We then spent an enjoyable few days meandering down the east of Tunisia visiting the Roman ruins at El Jem, the Berber towns of Matmata, Chenini and Tataouine, the fort at Ksar Ghilane and the island of Jerba.

Leaving Tunisia was reasonably straightforward although customs made us sit around for half an hour for no apparent reason before letting us leave. All the local cars heading to Libya were being pushed to conserve the last drops of fuel before they reached cheap Libyan supplies.

Libya

Getting Libyan visas had been a rather tortuous and expensive affair. We hooked up with two other travellers, met through the Sahara-overland forum, and got Jamal Fteis of Arkno Tours to send an invitation for the four of us to the Libyan Embassy in London (US$100 per visa). Having got template stamps for an Arabic translation of our passports at the Passport Office, we got Hamed Kalifa to do the translations and manage the process through the Libyan Embassy (£130 per person for an Express Service). We got the visas back within five days, and given one of these was New Year’s day, we were pretty happy.

We also used Arkno to help us get into Libya at the Raj Adjar border (US$270 – ostensibly 120 for the guide and 150 for the cost of paperwork). Nabil, our guide was excellent. He met us just after we left Tunisan customs and we waited while he did all the paperwork for us. This is all in Arabic and given the border officials weren’t especially welcoming and spoke very little English or French we were glad of his help. We got Libyan number plates, a carnet de passage with insurance, a permit which we assume is similar to a permit de conduire in Tunisia and a copy of the Arkno Tours invitation as well as stamps in our passport. Having paid Jamal in advance we had no money to pay and therefore did not change any money at the border. Customs was straightforward – no currency declaration and we were asked only to open the car doors and confirm that we weren’t carrying alcohol. The whole process took a bit over an hour.

We then followed Nabil to Zuara (60km towards Tripoli), had a coffee with him, changed some money and said our farewells. The currency black market in Libya seems to have dried up. We had ignored the swarms of money changers waving wads of Libyan dinars in Ben Guerdane on the Tunisian side of the border offering 1.3 for a dollar. We got 1.45 with the money changer in Zuara. In Tripoli the money changers in the Medina wouldn’t go above 1.5 so we changed at the bank in the al Kabir hotel for 1.53.

Despite what we had heard, we were surprised by how easy it was to get around Libya on our own. We were waved through most checkpoints and when asked to stop, it was only for the routine name, profession, father’s name etc. The only bureaucratic pain we encountered was the need to re-register with the police within five days. We ended up doing it on our own in Tripoli because we weren’t staying long enough at our hotel (the Qasr Libya) for them to do it for us. We followed the Footprint guide recommendation and got a taxi to the passport office (the Jawazat) – it would be impossible to find on your own. It was quite a palaver given the language difficulties but we eventually worked it out. You need to get two copies of two forms from a hut at the front gate (1 LD), have the forms filled in by a translator who sits under a tree outside the main building (2 LD) and then have your passports stamped in the office up the stairs round the side of the large building (5 LD). You can also get the registration done in Ghadames if you are going straight there and probably in most other major towns which may be more straightforward.

We had stopped at the Roman ruins of Sabratha on the way to Tripoli and were keen to continue on along the coast to Leptis Magna before heading back to Ghadames. Both sets of ruins are really remarkable and definitely worth the detour however keen you are to get into the dunes.

On the way to Ghadames we explored the ksour in the Berber villages of Yefren, Kabao and Nalut. Nalut’s ksar is a particularly fine example and has had some restoration work done recently. The Nalut Hotel, overlooking the ksar, is currently closed for renovations but should be a great place when it’s finished. We tried to get the Café Nassen el Jebel to put us up but although they were very friendly, they weren’t keen. We therefore had no option but to stay at Funduq Nasim (10 LD pp), which was disgusting. In retrospect, we should have driven on and camped.

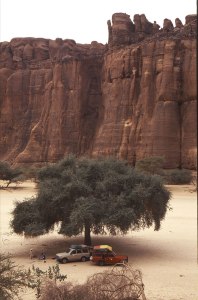

After exploring Ghadames, we crossed the Hamada al Hamra from Derj to Idri. Apart from straying onto a newer more southerly piste soon after leaving the tarmac which required a bit of slow cross-country to get back to the old piste, navigation was straightforward. Traffic was light and we didn’t see another vehicle the first day and only a couple of local cars on the second. The army at the remote Uweinat Whin checkpoint were particularly friendly, especially as we were able to lend them a 12mm spanner which enabled them to get one of their Land Cruisers going again!

After a night in Sebha, we went on to the Dawada lakes in the Erg Ubari. We should probably have taken a guide here as this was our first real session in the dunes. Our first day was pretty eventful with 3 hours of digging and we strayed into the wrong gassi while trying to get to Gabraoun al Jadid and ended up driving directly to Um al Ma. The upside was a night at Um al Ma lake, a magical place. We returned the following morning and got the right gassi and made it to Gabraoun without further problem. The tracks to the northern side of Um al Ma from Gabraoun had been covered over by the wind but we found the route after a walk and held our breath down the steep descents to the lake. When we finally got back to the Africa Tours campsite that night, we were exhausted but exhilarated at what had been a remarkable introduction to dune driving.

The following day we went on to see the prehistoric rock art at the Wadi Mathendous. We asked the caretaker of the Germa museum about permits for the site and he sold us two tickets for 6 LD. The police at the Km 128 checkpoint didn’t recognise these and wanted us to have a permit from the Germa police but they let us through anyway. We shared the Wadi with a pair of howling jackals that night.

We motored on to Ghat for a tour of the Jebel Akakus. The road to Ghat is very fast with the exception of the last 50 km which is broken up. The Akakus was the only place we used a guide in Libya. It is compulsory and would be very difficult to do solo given the numerous control posts in the mountains.

We did a three day circuit with a guide from Awiss tours, based at Mohammed’s campsite in Ghat. Awiss Tours are a family of Tuareg who clearly know the area well and entertained us royally. Camel tours appear to be their specialty. The landscape was stunning and we think we saw most of the highlights but four days would have been more comfortable. Our only gripe was that our guide, Cheick, the youngest brother, wouldn’t stop talking and he became very irritating.

We really enjoyed Libya. The desert scenery was fantastic. We felt perfectly safe driving on our own, camping where and when we wanted. The people were exceptionally friendly and despite the difficulty of getting visas and getting across the border, we didn’t feel the bureaucracy too stifling. The downsides are soulless hotels, a lack of vibrancy in the towns and difficulty in communicating in languages other than Arabic.

Al Gatrun to Agadez – the Marlboro Piste

Throughout our time in Libya we had been trying to gather information on the safety of the border areas and routes south. It was difficult to get reliable information and we received a whole range of advice on the security of the Marlboro piste. We also had the option of crossing the border to Djanet in Algeria or, allegedly, even going directly to Agadez across the Northern Ténéré from Ghat. However, we resolved to stick to our plan and returned to Sebha before heading south to Murzuk.

Turning off the main Murzuk-Timsah road, we knew we were heading into frontier territory. The tarmac roads in Libya are generally in good condition but this section is appalling and after a few kilometres we took to the sand to save our suspension – the eastern side of the road was easiest to drive on. It took us nearly 3 hours to get the 150 kms from the junction to Al Gatrun.

We arrived in Al Gatrun to find there was no fuel there or further south in Tajarhi and no prospect of any arriving in the near future. Although we could have got a few jerries from truck drivers in the town, we decided to do a return trip the following day to Zuweila to get the additional 150 litres we required – another day on the road from hell.

In Al Gatrun, we were soon directed to Mohammed Tager who lives in the old Italian fort on top of the hill in the centre of town. Mohammed has done a good job keeping the place in good repair and caters for the few tourists visiting the town. He put us up in the fort and charged us 17 LD per night (5 LD per person and 7 LD for the car).

Mohammed also helped us with the exit formalities which were as convoluted as the entrance. We managed to negotiate three different sets of police, customs and immigration in about three hours. The Tourist police required two photocopies of our passport and visas (Libyan and Nigerienne) which we were able to do in town. We didn’t get our 50 LD deposit for the car number plates back from customs despite our protestations. We were even forced to sign forms to say we had received the money!

Whilst in Al Gatrun we received a formal warning from the Tourist Police that we could have problems as a single vehicle, hardening our resolve to find a travelling companion. With very few tourists in Libya as a whole, let alone Al Gatrun, it quickly became apparent that going with a big Mercedes 6×6 truck was our only option. These huge trucks usually leave in the early evening as it takes them a whole day to unload, have their cargo inspected by customs, and reload. We introduced ourselves to the driver of one and he was very happy for us to join them as if it was the most natural thing in the world for two tourists in a TLC to want to travel with his truck.

We rolled out of town at 4pm but didn’t get more than 10km before stopping. We waited until nightfall and then the lorry was repacked with further cargo loaded on, beyond the view of customs. Packing continued through the night and we eventually headed off the following morning to Tajarhi. The going was painfully slow. We averaged 30 kph as the Mercedes groaned under the weight of its load and the 75 returning immigrant workers perched precariously on the roof.

The sand fields beyond Tajarhi were a graveyard for trucks. We passed four that had been broken down for days. The occupants of our truck enjoyed throwing cigarettes and dates to the stricken passengers and watching the ensuing scramble. We had to choose between driving in the firm truck tracks with the risk of bottoming out or making our own tracks in the sand and getting stuck. We used both methods and got through needing only two quick recoveries. Once through the sand fields we kept driving along a rockier piste before stopping at midnight for the night.

We continued our slow progress the following day on a much more westerly route than the piste shown on the IGN map.

By lunchtime we reached a Libyan military base with a temporary airstrip (N22° 47.8 E14° 01.3). Customs officers were in evidence and serious negotiations were required to prevent the Mercedes being unloaded for a further inspection.

By early evening we reached a further Libyan army checkpoint right on the border (N22° 39.2 E14° 05.4) where we were warned of local bandit activity and were advised to stop for the night. We pulled up just off the piste within sight of the army base and were joined by a further Mercedes – other trucks however continued past us during the night.

We finally reached Madama by lunchtime the following day and formally entered Niger a full three days after leaving Libya.

In Madama, a convoy of five empty cigarette lorries and two military Toyota pickups had just left for Seguedine. We were keen to join this faster group and tried to get through the formalities as quickly as possible. Customs charged us 20,000 CFA for a laisser passer – with no exchange facilities, they let us pay US$30. The police gave us an arrival stamp and we ended up giving them US$10 in lieu of a random demand for 10,000 CFA so we could get away and catch up with the convoy which we did after a frantic 12km dash.

The terrain here was much easier and the lorries charged south at high speed quickly losing the army escort after one of the Toyotas got a puncture. We regrouped at the Mabrous well and then it was the turn of the Toyotas to tear off, leaving us behind when we stopped to make repairs to one of the lorries. We were left wondering whether there was any logic to the escort at all. After a lengthy stop to fix an ailing lorry transmission, we kept going through the night to arrive at the Dao Timmi military base at 2am. The piste between Mabrous and Dao Timmi is rough and heavily rutted with lots of risks of bottoming out. The lorries were pushing on in terrain that was much easier for them. We narrowly escaped being shunted from behind by a brakeless lorry several times.

We descended to the picturesque oasis at Seguedine, with small fort and saline, around lunchtime on the fifth day. There we were forced to employ a local Tubbu guide, Laouel Barka, in line with the current stipulation that all tourists should be accompanied by a guide when traveling in the Ténéré (15,000 CFA per day). Although initially exasperated by this demand, given we already had an escort and only wanted to continue for a further half day to Dirkou with the same convoy, we decided to use it as an opportunity to explore Djado and we waved goodbye to the trucks.

The local army chief, Lieutenant Ahmoudou Bossi, who had tried to help us reach a compromise with Laouel, invited us to spend the night in his compound and arranged for us to do a day trip to Djado without obtaining the requisite “feuille” in Dirkou. The following day we set out with Laouel to Chirfa, Djado, Djaba and Orida. The hassle factor seemed high in Chirfa and we were glad of having a local guide. Even though Djado is the most famous sight, we thought it definitely worth the extra effort to make it to Djaba and Orida and were disappointed we could not spend more time here. The army say that this area is now free of rebel activity and the Tubu checkpoint before Orida has gone – they wanted to make sure we weren’t going up to the plateau though. We bought two jerries of diesel in Chirfa on the way back (US$26 in lieu of 17,000 CFA), continued on to Seguedine for another night with the Lieutenant, and on to Dirkou with Laouel.

In Dirkou, we got a “feuille” to cover the rest of the journey to Agadez for 20,000 CFA – the price seems absolutely random. We stayed at Jerome the fuel seller’s compound. Jerome died in late 2001 and the place is now run by his son, Sergeant Boubacar Mohamed. We paid 65,000 CFA for a meal, a place to sleep and 200 litres of diesel. We thought this was generous as our friendly Libyan trucks had by now turned up in town and were willing to sell us a drum of diesel for 45,000 CFA. We also took the opportunity to grab a beer at Mariama’s Bar, our first for weeks.

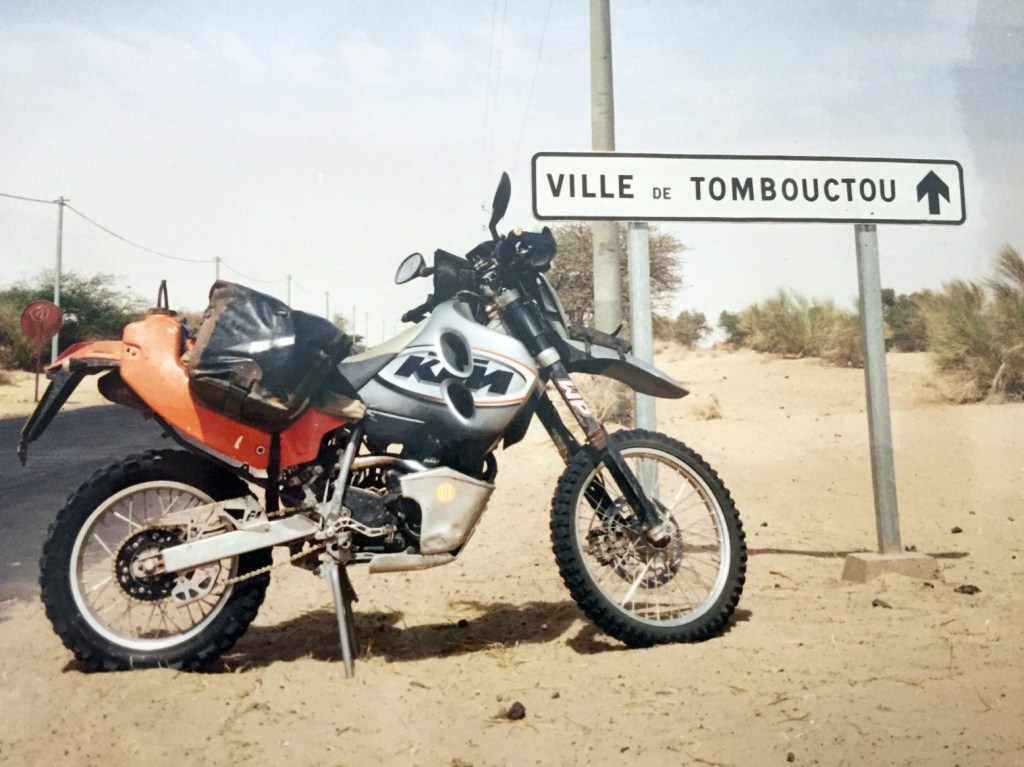

Laouel, who had turned out to be somewhat mercurial, decided he did not want to continue to Agadez and we were also happy to be rid of an unstable character. Sergeant Boubacar arranged a new guide for us and we visited Bilma and then continued to Agadez via Achegour and the Arbre (50,000 CFA for the guide for however long it took). We were taken on a route that followed the balises between Kafra and Achegour. The sand was pretty soft and the going was slow at high revs and high fuel consumption. 50km after the Achegour well we came across a broken-down truck with 70 people who had run out of water. In exchange for some diesel we did a return trip to the well and brought them 250 litres of water. After spending the night with the truck, we continued on to the surreal Arbre de Ténéré. The section between the dunes just southeast of Adrar Madet and the vegetation-covered dunes close to the Arbre was very fast on hard flat sand.

We spent the final night at the small Tuareg settlement at Barghot. We had bought a gazelle during the day so feasted on gazelle stew, a great change from tuna pasta. Arriving in Agadez, it had taken us ten days to cover the 2200 kilometres from Al Gatrun with remarkable traveling companions and fantastic scenery. We were tired but triumphant.

Agadez to Tunis

We celebrated our successful desert crossing by booking into the Pension Tellit. This Italian-owned small hotel with only five rooms overlooking the Grande Mosque is beautiful and was a great escape from the stresses of travel – we paid 30,000 CFA per night for Room 4. The linked Restaurant Pillier is also excellent and equally expensive.

We used our time in Agadez to rest up and prepare for the next leg. We were able to refill a Camping Gaz 907 cylinder in the market but the internet has yet to come to town – the tour agencies are supposedly trying to organise the establishment of a connection.

We were aware of recent robberies, including the armed carjacking of a TLC from an Italian woman in the centre of Agadez in January, and felt nervous about security. There were unsavoury characters hanging around both the Hotel d’Aïr and Pension Tellit wanting to “buy” our car. The hotel organise a couple of policeman to sit outside to keep husslers away from their guests so they are also clearly concerned. We stored the car in the hotel’s secure compound on the outskirts of town. We also used the well-established French-run Dunes Voyages to get us a Tuareg guide for a two-and-a-half day trip in the Aïr through Timia and Iferouane, ending in Arlit (70,000 CFA including feuille) and left discretely early one morning.

We were a little disappointed with the Aïr mountains. The driving was hard over slow rocky terrain – it took 8 hours to do the 235km to Timia. The mountains and irrigated gardens were beautiful however and maybe we were just tired. We were told of continued bandit activity in parts of the Aïr, but our guide, Issaka, was excellent and we felt fine – maybe we just got lucky though.

We arrived in Arlit on the morning of the third day and didn’t stop. Entering town, we were hassled by a policemen because we hadn’t bought any insurance but the police in the centre were more friendly and let it pass given we were on our way out. We were now on our own again. The piste to the Assamaka border post was fast and easy to follow and we breezed through the exit formalities. There was one money changer selling Algerian dinar and euros.

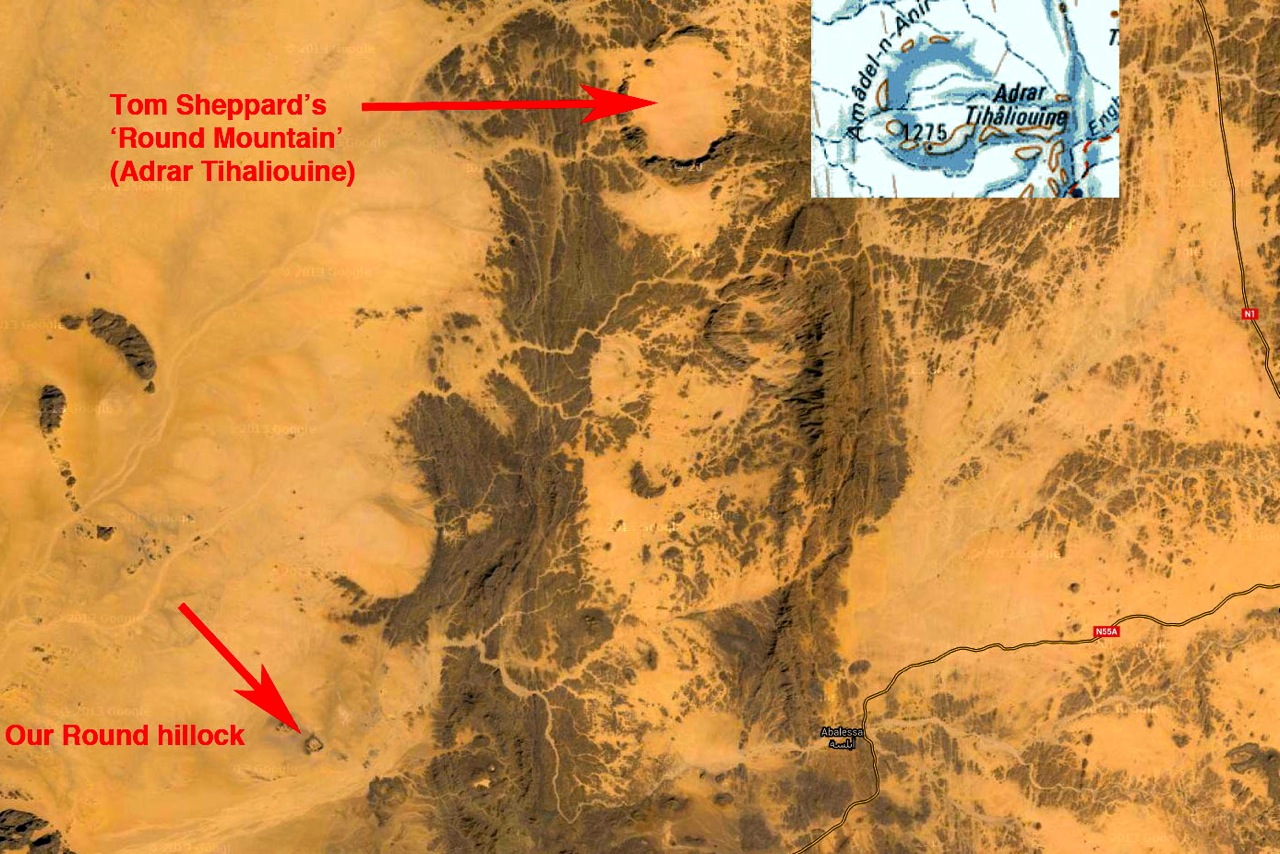

The border area here is annoyingly off the edge of the Agadez and Tamanrasset IGN maps and with no waypoint we just headed north following tracks. We ended up missing the border post and drove straight into In Guezzam unchallenged. With the help of a local we tracked back the 10 or so kms and found the checkpoint (N19° 28.9 E05° 47.5).

Entering Algeria was easy with very friendly officials. We got the usual stamps, certificate and did a currency declaration. Customs asked us about cigarettes and “red” (whisky), but only wanted to check the chassis tied up with the number on our Vehicle Registration Certificate and didn’t do a full search. We were told to buy insurance in Tamanrasset which we subsequently did at CIAR near the Tourist Office (2,112 Algerian Dinar for 10 days). There was no fuel at In Guezzam but we could have got some at the police station if we needed it – this time we were prepared and had enough to get us to Tam.

There is lots of evidence of roadbuilding between In Guezzam and Tam with three different companies working on different sections. We didn’t find any ready to drive on and used the piste until 40 kms before Tam. We found route finding and driving very easy and we did Arlit to Tam in under two days including a night on the piste in Algeria.

In Tamanrasset we stayed at the Gite Saharienne run by the Bahedis. We had used their agency, Agence Tarahist, to get a certificate d’herbegement faxed to the Algerian Consultate in London so they would issue our visas. We had tried just a straight faxed reservation from a hotel but the Consulate wanted a certificate. Agence Tarahist charged us 330 CHF (205 Euros) for the invitations and a night’s dinner, bed and breakfast at the their lodge. This seems expensive in retrospect, but at the time, we were quite happy to pay for Agence Tarahist’s efficiency when we needed it. The lodge is also a great retreat and the food exceptional.

There were long queues for diesel in town but we were ushered to the front, afterwards leaving to do the Assekrem circuit, up by the Afîlal guelta and down via Ilâmane. Sunset and sunrise at Assekrem was fantastic and we had to adjust to being part of a group of tourists for the first time on the trip. The way down was very slow on an atrocious track but it was just about manageable (5 hrs). One of our side bars broke off but we put it down to 3,500 km of piste.

After a four hour delay waiting for diesel in Tam, we set off the next day on the easterly piste via Temékerest to Ideles. We got only a little beyond the Temékerest “waterfalls” before our exhaust began to give us major trouble, presumably another casualty of the return from Assekrem. Makeshift repairs the following morning didn’t last so we returned to Tam to get a new section brazed on.

When we finally got going, we found the piste to Djanet very enjoyable. We passed through Ideles (diesel available, no petrol) and we spent a stunning evening by a small dune bank under Telertheba mountain. We made Djanet the following day via the Erg Admer. Driving in the erg was pretty easy but we were glad of 1.2 bar to get up the first ascent. We stayed in the Hotel Zeriba in Djanet (1,200 AD for double with breakfast). The place was full of tourists which seemed to reflect lack of alternatives rather than the quality of the accommodation.

Short of time we got the Zeriba to organise a one day walk on the Tassili Plateau to Jabbaren, supposedly the second most important site of prehistoric rock art (5,700 AD for the two of us with a guide). The walk was beautiful and if you are time-constrained, there is a lot of art in a small area. One day was manageable – we left at 0600 and were back by 1730, tired but certainly not shattered. We didn’t want to spend another night at the Zeriba so camped in the dunes just outside Djanet.

We then headed north via Illizi and the piste to HBG. Driving out of Illizi, we found it hard to locate the piste and found ourselves too close to the dunes which ended up in difficult terrain. We tracked back and once we found the piste the route was obvious all the way. We found the driving slow on day one but enjoyed the opportunity to spend more time in the dunes.

We sped through the Gassi Touil and after a night in Hassi-Messaoud went on to the Tunisian border. Stone-throwing kids were well in evidence all the way from Touggourt to the border. We avoided damage through a combination of speed and screaming at kids about to hurl rocks. The police are well aware but don’t seem to want to do anything about it.

Leaving Algeria was slow with incompetent immigration and customs officers but we made it through in an hour and were back to the comparative civility of Tunisia. We mosied back to Tunis and reflected on our travels at Restaurant Dar el-Jeld in the medina, a fittingly grand place to end what was a remarkable and unique journey.