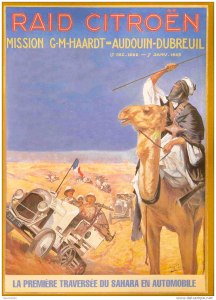

Part of the occasional Sahara A to Z series

Hang around long enough and you’ll get the full set

Pictures from Emile Leray’s website [dead link] and the web

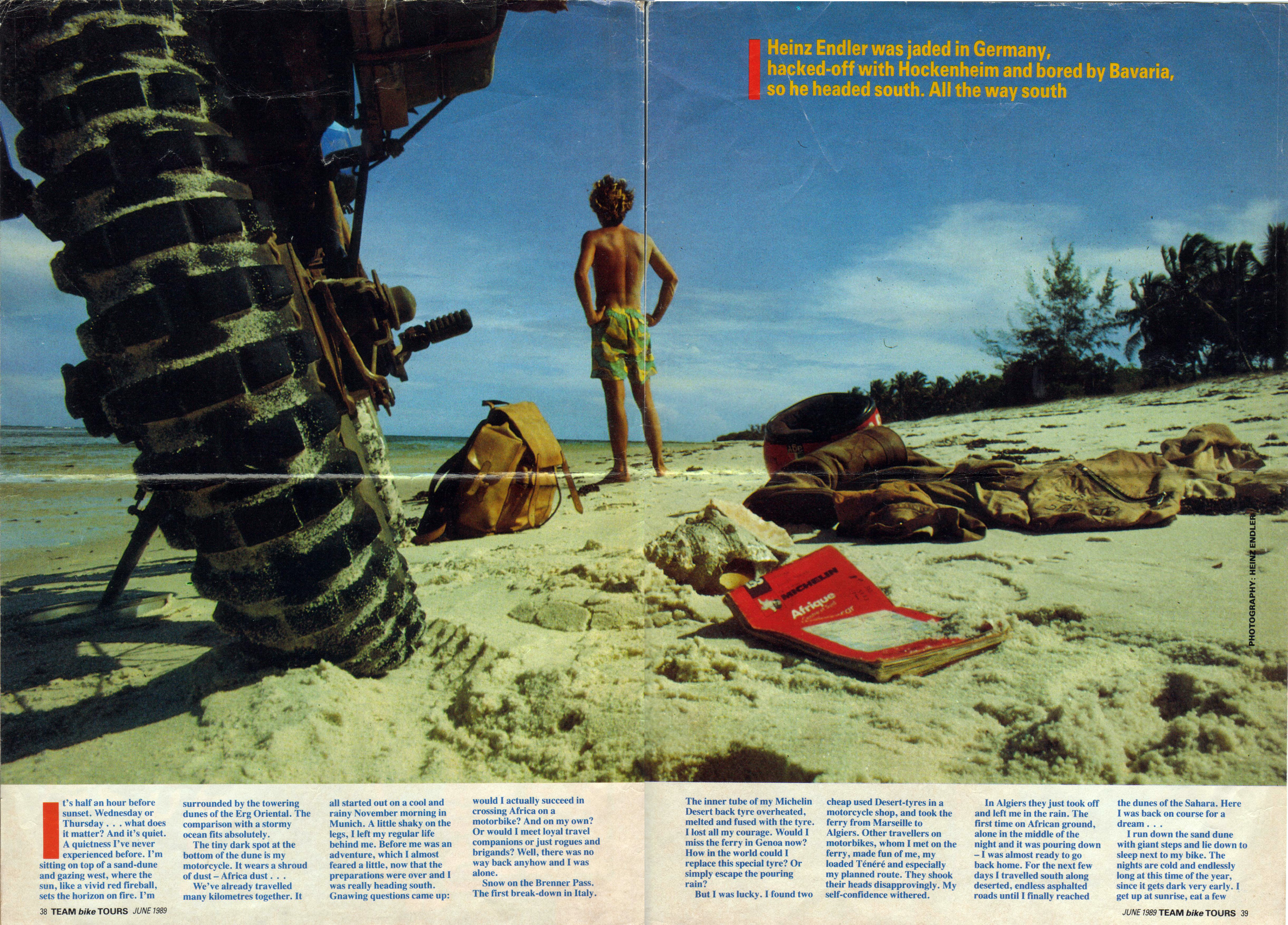

In July 2012, a couple of years before fake news had become a thing, online media tripped over itself to syndicate a compelling Saharan survival story evoking the gripping 1965 desert drama, Flight of the Phoenix.

Then, five years later a video appeared on youtube (below) where the aged and batty-looking French adventurer again recounted his incredible desert caper.

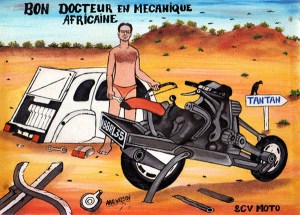

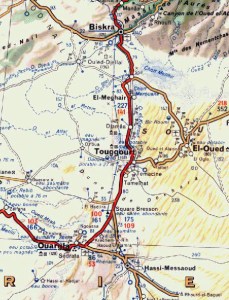

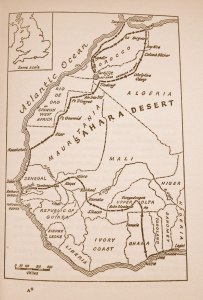

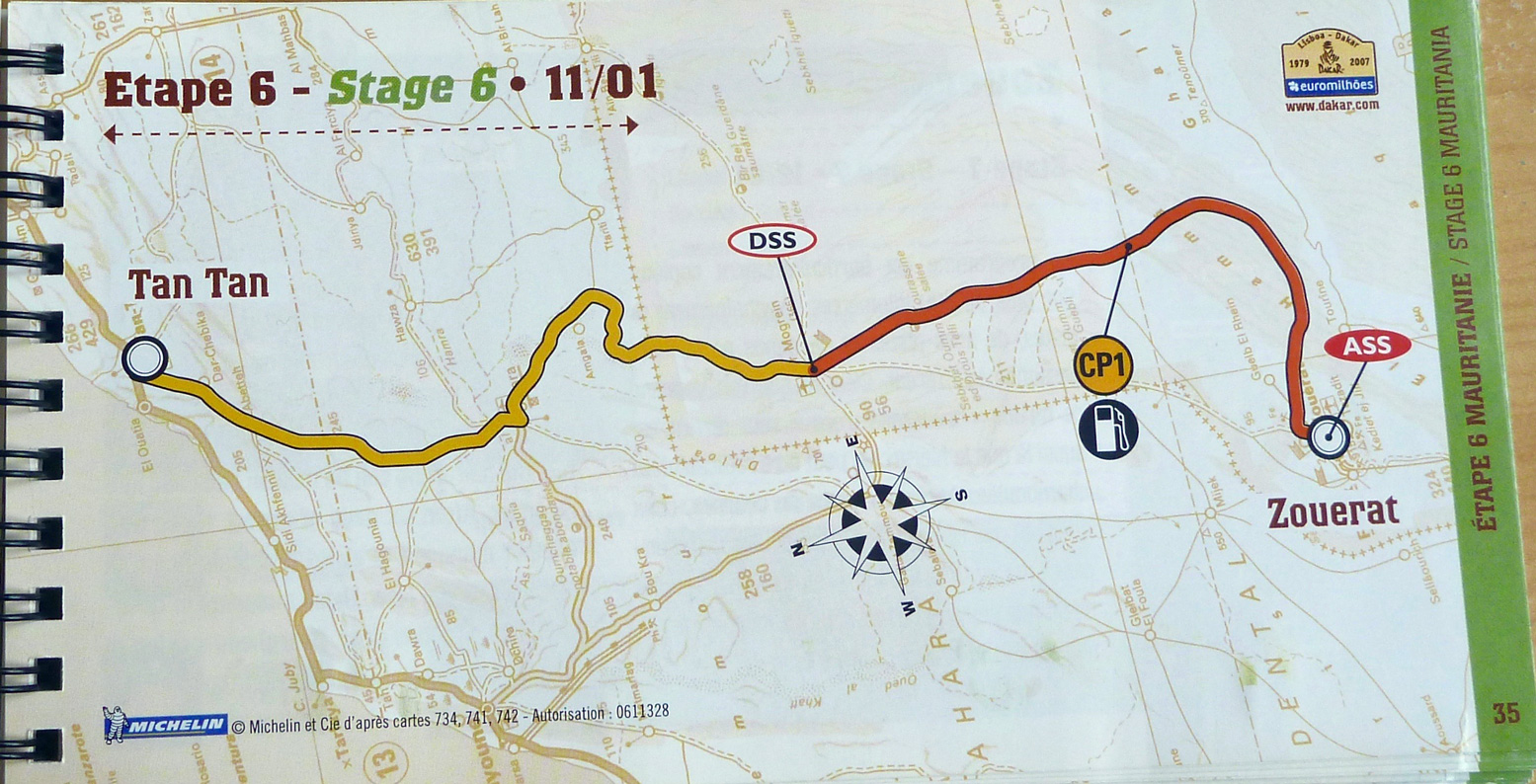

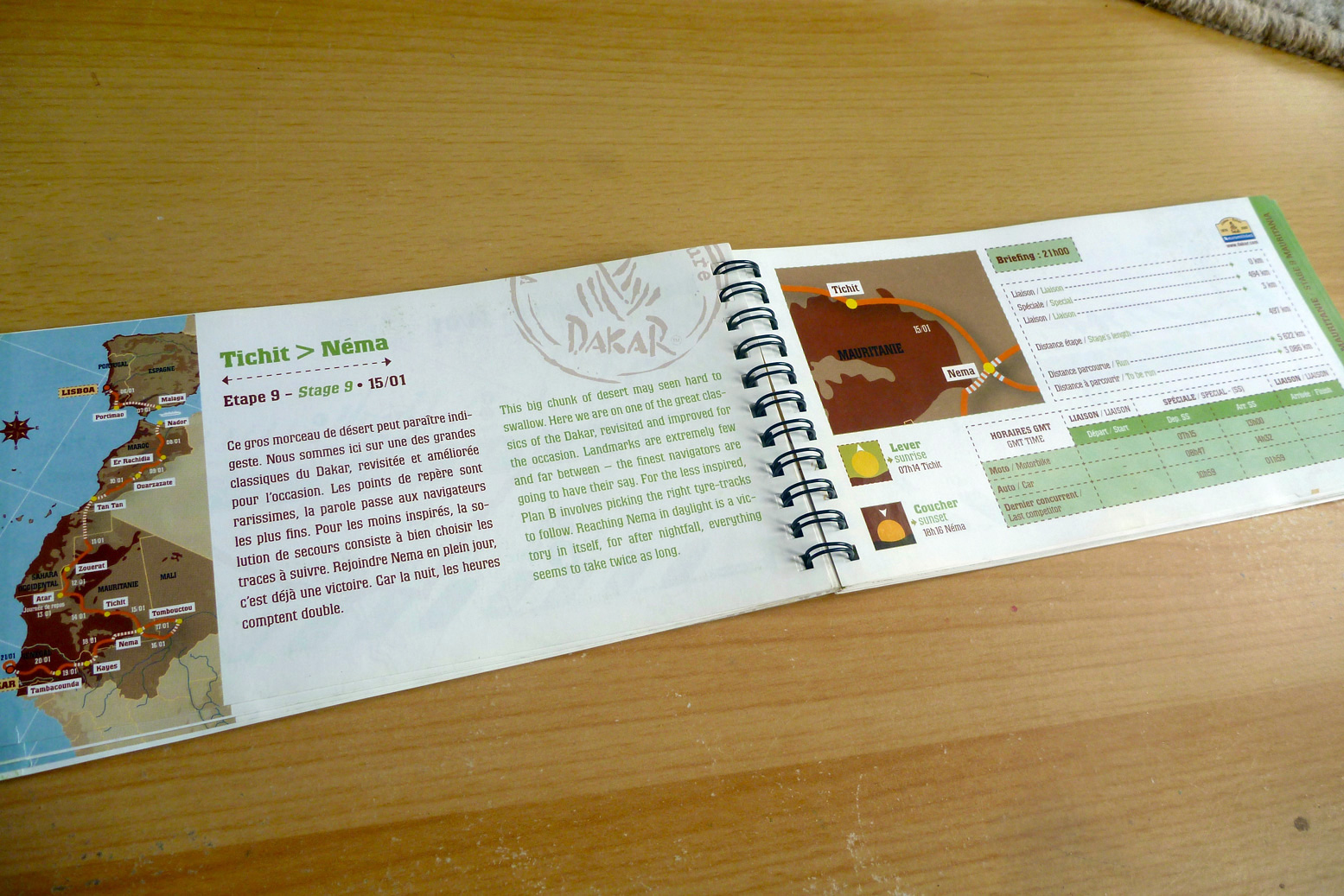

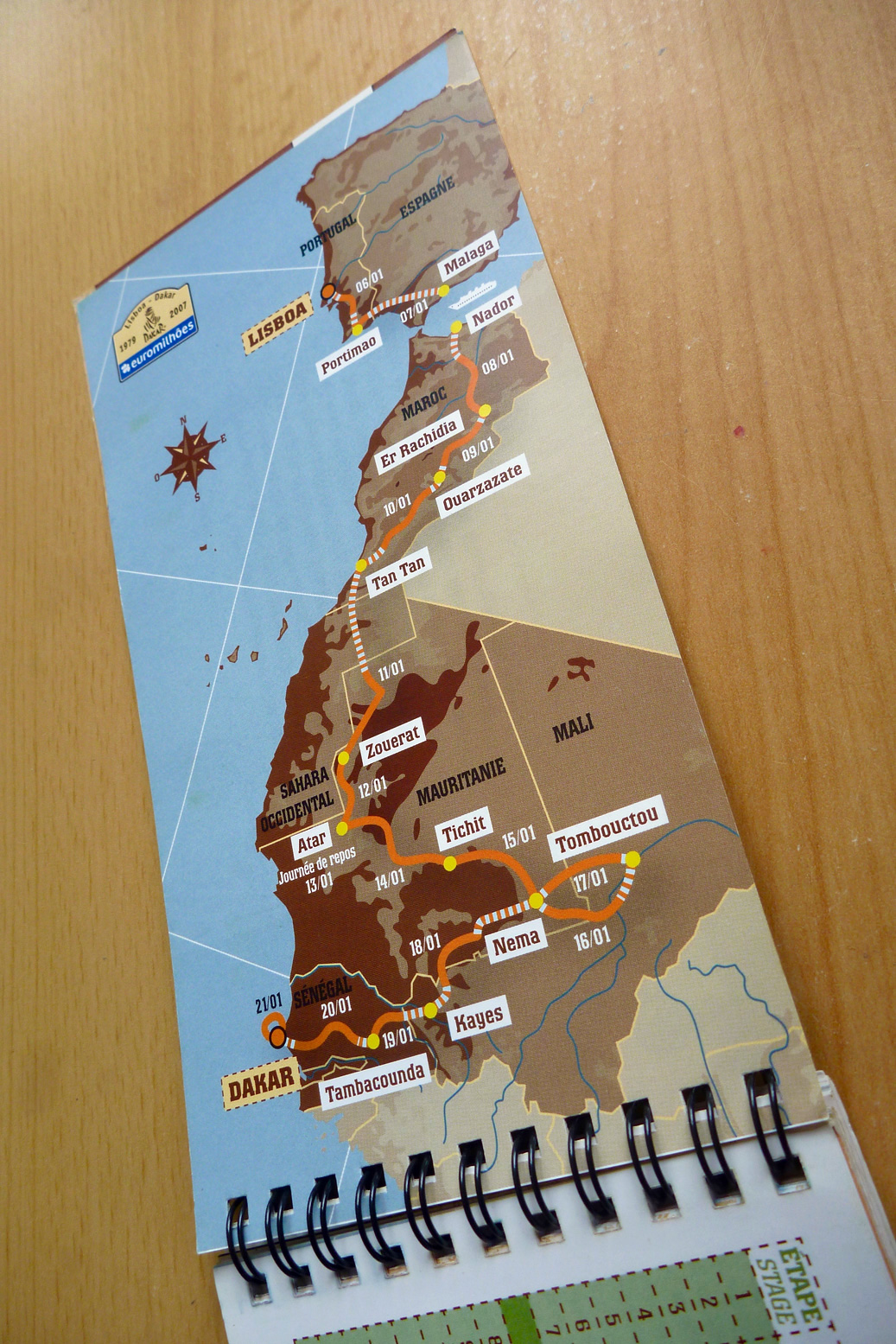

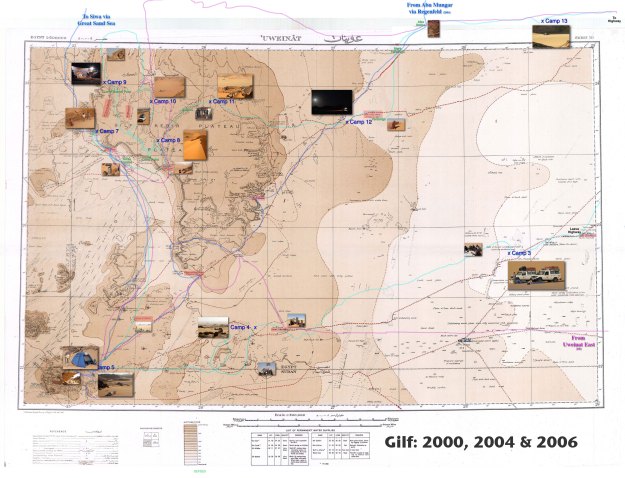

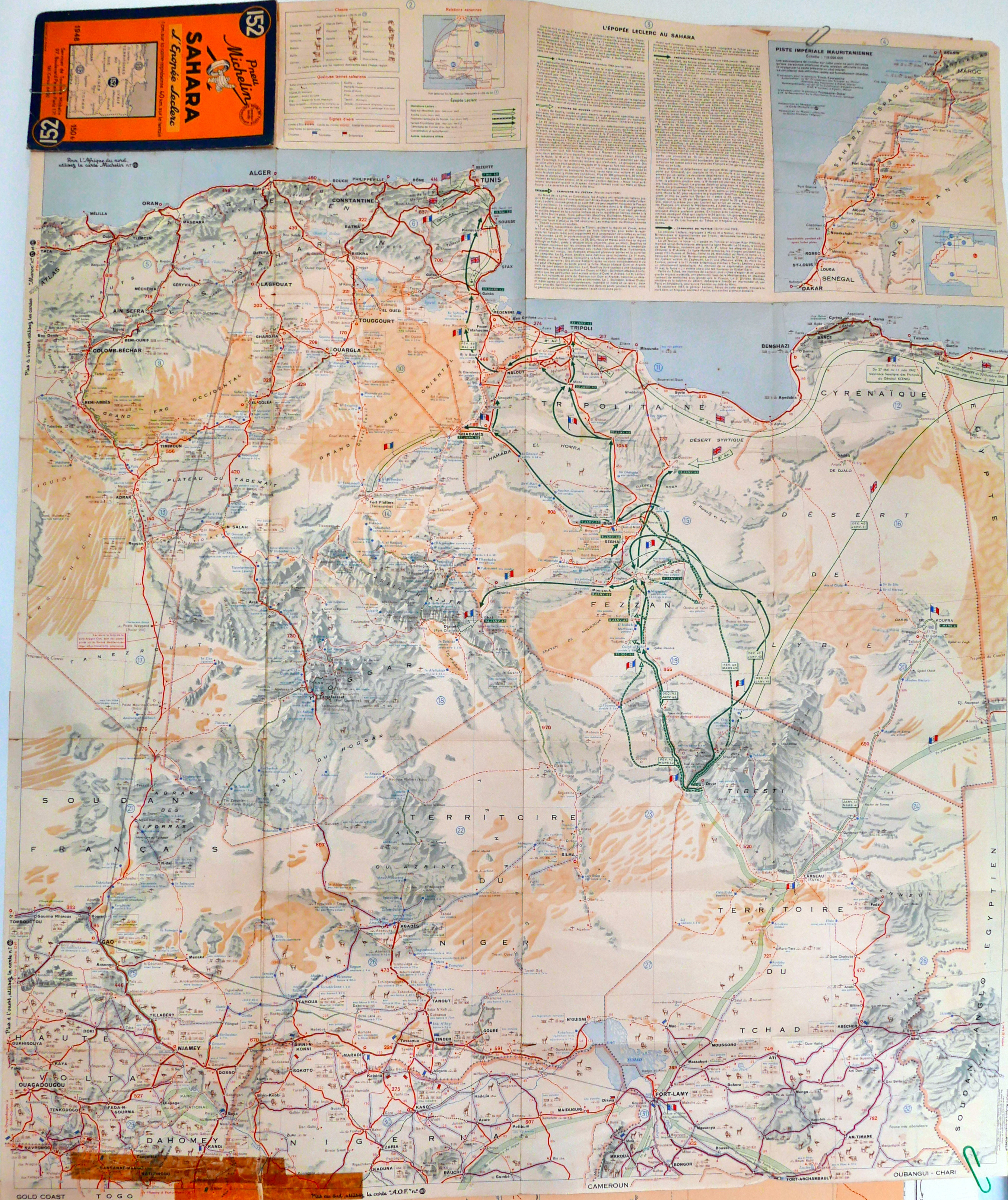

Back in 2012 full details and motivations were skimmed over, but the story goes that in March 1993, 43-year-old Frenchman Emile Leray set off from Tan-Tan near the Moroccan coast to drive his Citroen 2CV east to Zagora – more or less Route MW2 from my Morocco guidebook (below), followed by MS8 from Tata.

But with the Polisario ceasefire just 18 months old and frequently being broken, at Tilemsen the Moroccan army stopped him from continuing south towards Mseid, the former Polisario front line. Leray turned back towards Tan-Tan, but not before incurring some animosity from the army by refusing to give a soldier a lift back to town – a common request at remote Saharan checkpoints.

Just west of Tilemsen, Leray ‘had an idea’. He decided to circumvent the checkpoint to the north (see MW1 KM22), and rejoin MW2 eastwards. But once on the piste (or ‘off-piste’, as claimed) one of the 2CV’s suspension arms broke after hitting a hole too hard. With ten days’ provisions on board but reluctant to easily walk-out and leave his car vulnerable to theft, he decided to strip his crippled Citroen and rebuild it into a rudimentary motorcycle, then ride out as if nothing much happened. The unusual powertrain and suspension arrangement of a 2CV makes such a conversion plausible.

The way the story was initially reported in English – using images shot later in a quarry (above) – Saharan know-alls like myself were initially sceptical. If it really happened why not just walk back half a day to the road?

I researched the yarn more closely for my Morocco guidebook and came across his own account published in a 2CV enthusiasts’ magazine a decade after the events. A faint ring of truth came through. Perhaps he did build the 2CV bike, but not in quite the circumstances he claimed.

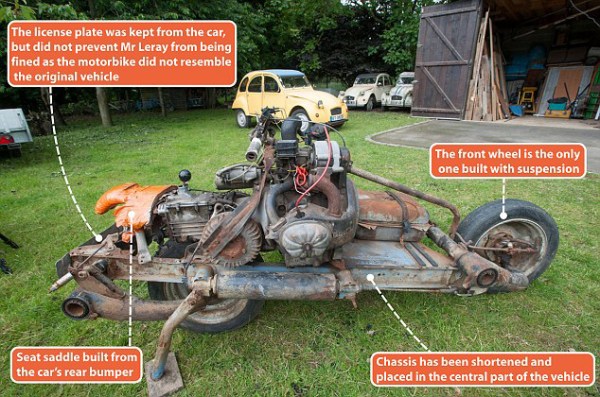

As the TV show, Mythbusters proved for themselves, his contraption was barely rideable (left) and within a day of leaving the rebuild site, Leray says he was caught by a patrol while camping in the desert and instructed to lead them back to the car’s remains to corroborate his story. Ironically, he goes on to claim (with convincing documentary evidence) that he ended up paying a 4500-dh fine (about €450) for driving a vehicle which did not conform to the one he originally imported to Morocco a few weeks earlier, even though he’d taken pains to tack on his ‘Steel Camel’s’ original license plate.

I believe the 2CV bike was indeed built in the desert, much as Leray claims, but he set out from France with the explicit intention of performing this task. Otherwise he’d have walked out like any normal person in a similar situation.

His claimed unease about leaving his stricken car doesn’t ring true, let alone the spontaneous idea of making it into a two-wheeler. Tellingly, in 2006 Leray went on to build a ‘2CV boat’ in Mali. He clearly likes mucking about with 2CVs. Fair play to him!

Below is the translated story as posted on Leray’s website so you can form your own impression. Bear in mind there’s no reason to believe this account, but it may have been the original version.

In March 1993 Emile Leray set off to follow a route from Tan-Tan to Zagora. He left Tan-Tan with the required reserves of fuel and provisions as well as tools to keep his old 2CV on the road. As soon as the Royal Gendarmerie arrives, they strongly discourage him from continuing further because the zone beyond Tilemsem is prohibited, following new developments in the conflict between Morocco and Western Sahara. Emile must obviously turn around and the soldiers are asking him to take a passenger back to Tan-Tan.

Analyzing the situation, and seeing his project thwarted, Emile claims an insurance problem that does not allow him to take passengers, arguing that his 2 CV is already very loaded. He knows full well that in Africa it’s seen very badly to not take soldiers aboard his car in these circumstances. He claims naivety and misunderstanding in adopting the attitude of a tourist not familiar with local customs.

Emile then returns to Tan-Tan under the disgruntled and disapproving look of the soldiers. He starts off at a good pace as he’s afraid he will be followed and he wants to remain out of sight of those whom he has just left. His plan is to bypass the area off-piste and return to his original direction … After a few kilometres he leaves the track to the north and traverses uneven and rocky ground.

After bouncing more strongly, the car jumps and brutally strikes a rock. He must stop because the 2CV does not respond very well. And for good reason – a folded wheel arm and broken spar …

Émile organizes his encampment around the broken 2 CV and reflects on the situation. He is a few miles from Tan-Tan which he could reach on foot, but he runs the risk of leaving is car certainly in bad point but still able to attract theft, including its equipment. In the desert nothing is permanently lost, especially for the one who knows where to look.

He has enough food and water so makes a decision which is to say the least, amazing: from his wreck, he will build a two-wheeled machine! One by one he carefully considered all the technical obstacles that this entails, and this master of African bush mechanics has all the tools and the elements to succeed in the task.

The next morning he began to dismantle the 2CV, first removing the body which he will use as shelter against the cool nights and sandstorms. Having no long-sleeved shirts, against the burning sun he makes sleeves from a pair of socks. With what remains of the car, Emile Leray will try to build a motorcycle. Overnight he mentally reviewed all the stages and difficulties involved in this rather crazy project … A project that he had probably imagined for a long time but without having had the opportunity to realize it.

The wheel arms (to be removed with a hacksaw) are nested upside down on a reduced chassis of the front and rear side rails. The engine and the gearbox are then placed on the chassis in the center. Space should be reserved for the battery and the fuel tank and to keep space for luggage without neglecting the layout of the steering system.

The most surprising thing about this 2CV motorcycle is the transmission. It was inspired by the Vélosolex moped idea (right): the engine drives a drum which in turn turns the tyre by friction, and which, by the laws of physics and mechanics, obliges it to roll with the reverse. Disassembling the gearbox to reverse the differential would have been too risky in this universe of sand …

It seems unthinkable to assemble this machine in the desert without the help of a drill and welding station. All parts were assembled by screwing. When drilling, it will be done in the African way: the piece of metal is folded to 90 ° to form an edge. At a fixed point this edge is weakened by a hacksaw or round file. At the limit of the drilling, the piece must be replaced flat to perforate the filed point with a hammer or a needle. The assemblies were made as much as possible according to the original holes of the chassis or engine-box unit.

The rest is only a matter of time dependent on the quantity of his provisions. Émile believes he must spend three days building his bike – in reality it will take twelve …

There was a great deal of uncertainty to carry out this project and it wasn’t so easy to realize as one might think. The possibility of failure remained present throughout the adventure, giving some anguish to the stranded mechanic.

The 2CV motorcycle was obviously not conceived for the sake of comfort, it is a rather secondary notion that was not imperative in what we can call the specifications. The prototype has therefore not benefited from some desirable improvements. It should be noted that, for example, the exhaust is free, so the nose and the ears are affected greatly by the engine’s gases. The bike does not have a brake, nor does it have foot rests which allow some control of the trajectory with the feet, because the craft lacks stability. On the first test the bike fell over, causing a great scare to Emile, who almost found himself crushed under his 200-kilo machine.

The arrangement of the clutch and accelerator controls were particularly tedious. It was necessary to dismantle, adjust and reassemble the parts for optimum operation. Similarly, the tests were punctuated by frequent falls. To lift the two-wheeled steel camel proved particularly physically difficult … All these circumstances contributed to prolong Emile stay in the desert. The final day was be spent adjusting and testing and cleaning the bivouac site.

It was an occasion to immortalize the moment thanks to a small camera with the trigger connected by a long wire. Émile poses in the middle of a place that in March 1993 was the theatre of his unusual feat.

He leaves the next afternoon leaving the parts that he will not use in the body shell of the 2CV. He takes with him the rest of his food (more than a litre and a half of water), the bed, the tool box, not forgetting maps and compass. A small foam mattress and a towel sewn together will serve as a tent.

After a bumpy ride and a few stops for mechanical improvements, he encamped and slept at the edge of a track. In the night, he is awakened by three soldiers in 4×4, one of which immediately recognizes the “tourist” of Tilemsem. Very irritated to find him in the forbidden zone, he strongly doubts Emile Leray’s explanations; an accident followed by the transformation into a motorcycle. Intrigued by the machine, but totally incredulous, the soldier demands to see the carcass of the 2CV to have proof of this incredible story.

The officer puts an armed guard by the tent and the motorcycle, then embarks with Émile in the 4×4. After an hour of research in the dark, the remains of the 2 CV cannot be found. Back at the camp, Émile is allowed to rest near the motorcycle until dawn, guarded a hundred meters away by the military in their 4×4. The next day, the carcass was found and the soldiers relax. Émile will learn later that his interlocutor wanted to recover the abandoned pieces for his brother-in-law …

In the early morning, Emile was ordered to take his motorcycle back, and ride in front of the 4×4. The convoy sets off slowly towards Tan-Tan but several falls seriously annoy the soldier, pestering against this unstable machine. Eventually the soldier calls by radio for another 4×4 to come to recover the 2CV motorcycle.

Arriving at Tan-Tan on April 6th, things get complicated with a lot of bureaucratic hassles. At the provincial governor’s office, a report is drawn up, as well as by the Royal Gendarmerie. The vehicle is impounded

Emile has the disagreeable surprise of learning that he has to pay a tax of 4500 dirhams. He is very unhappy because the customs officers had spoken to him on the eve of mere formalities. The vehicle is regarded as dangerous and no longer corresponds to the description of the registration documents.

“Delay in importing a non-conforming vehicle” is the charge, and by paying the fine he can regain his freedom and recover his contraption, but not be allowed to drive it.One could say a lot from this misadventure about the complicated relations between Africans and Europeans on the issue of money ...

The next day Emile is summoned to sign the forms to exit the territory, and leave for France. He thinks he should come back as soon as possible to get the bike back, but by then he must find a place to park it. There is no question that he leaves her in the pound, it may cost him dearly, and the place is not guarded. A customs officer who is more sympathetic than his colleagues offers to take the steel camel home while waiting for him to return to Morocco.

A month later Emile made the 3500-km journey between Rennes and Tan-Tan with another 2CV to pick up his motorcycle, now dismantled in three parts …

Since then, the steel-motorcycle camel has enjoyed the honors of the press and participated in a few events such as the Aventure and the Inventors of Rennes, the fiftieth anniversary of the 2 CV in Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, Without forgetting the Motards have heart.

Émile returned several times to Africa, and in 2006 took a new opportunity for the Doctor of African mechanics to exercise his transformational talents on the steel camel [below]…

For more information: full story and technical details in 2CV Magazine March-April 2003.