A few photos from the one-week February 2020 tours, showing the new first-day route over the High Atlas, off-road.

Next tours in November.

A few photos from the one-week February 2020 tours, showing the new first-day route over the High Atlas, off-road.

Next tours in November.

‘Free Solo’ is a documentary covering Alex Honnold’s mind-boggling, rope-free ascent of El Capitan in Yosemite, California in 2017 (left). If you’ve seen it you may recall that, among other places, Honnold practised on a hidden cirque of cliffs surrounding the scattered hamlet of Taghia, buried about as deep in Morocco’s High Atlas as you can get. A couple of rudimentary gites cater for visitors but, even among Moroccan know-alls, unless you’re a rock climber you’ll have never heard of Taghia. The only way in is a four-mile mule trek through a canyon from the valley head at the equally obscure outpost of Zuweiat Ahansal, an hour or two’s ride south of Rocher de Mastfrane, better known as the ’Cathedral’ (below).

I rocked up at Zuweiat one lunchtime just as a group of young American climbers were spilling out of a taxi, and continued over the bridge to the edge of the old town. I pulled over for a snack and, unsure of the way and not wanting to blunder on, asked a passing local whether it was possible to ride a bike to Taghia and if yes, which way?

‘Oh no’ said the old man. ‘You can only get there on foot.’

I finished my snack and thought it over. Back by the bridge, I sought a second opinion from some more worldly looking dudes hanging out outside the post office. They were eyeing up the new, North Face-clad arrivals and one spoke good English.

‘Yes, I saw you pass and was going to say, you can’t ride your moto to Taghia.’

It turned out he’d worked on the Honnold doc as well as other National Geographic features (below) and, reading his manner with my finely tuned bullshit detector (which they now hand out free at the border), it didn’t sound like the usual bragging. After that, he switched seamlessly into sales mode, offering lodgings and guides.

‘Maybe next time’, I said. I genuinely did hope to visit the mysterious valley, but the weather forecast was a bit shaky for the next couple of days. I wanted to get out of the mountains, not stuck in them.

A year or two earlier a bike-riding climber who’d visited Taghia suggested to me that a small bike (like my Himalayan) could probably reach the cirque following the riverside mule path.

While that may be true, I figured just because I could, did I have to – or even, should I? The local guide may merely have been protecting his mule-trekking services, but I like the idea of leaving some of the world’s wild corners unspoiled by the putter of mechanized transport. As I was about to be reminded, there’s plenty to see in Morocco on a bike or in a 4×4, but there are many places in the world which are best reached by less intrusive human-powered transportation. That’s what makes them special.

2024 and I heard they’d finished the track into Taghia. James and I were in the area recce-ing route for the M4 book. A few months later I wrote this in Adventure Rider magazine.

Add a few wraiths of mist plus some digitally enhanced pterodactyls, and the narrow chasm which leads into the Taghia gorge could pass for a scene from Game of Thrones. Burrowed deep in Morocco’s High Atlas, the isolated Berber hamlet beyond was only accessible by mule. So I was told in 2018 when I tried to reach Taghia on my Himalayan. Now they’ve carved a motorable track, so we rode down through the defile, crossed and recrossed a stream, and found ourselves in a small cirque or valley head surrounded by sheer, 3000-foot limestone terracotta crags. I’d not seen a place like this in Morocco. Alex Honnold came here to train in seclusion, prior to soloing Yosemite’s El Cap for the Free Solo movie. He did so by free climbing all three of Taghia’s hardest faces – 6000 feet of big wall soloing – in a single day. “It’s pretty freakin’ next level” he observes with characteristic humility in Before Free Solo, Edge of the Unknown’ (on YouTube).

Set off with a mission to join some dots for my spring tour in a couple of weeks.

Mission accomplished. Dots joined.

More about the bike here.

High Atlas village

High Atlas village

Another new road from nowhere to nowhere much. I suppose it helps stir up the local gene pool.

Another new road from nowhere to nowhere much. I suppose it helps stir up the local gene pool.

One of these days I’m going to watch a youtube doc on how they build mountain roads.

One of these days I’m going to watch a youtube doc on how they build mountain roads.

Above the clouds at 2500m or about 8300′ in old money.

Above the clouds at 2500m or about 8300′ in old money.

An isolated juniper tree that’s managed to dodge the village wood burners.

An isolated juniper tree that’s managed to dodge the village wood burners.

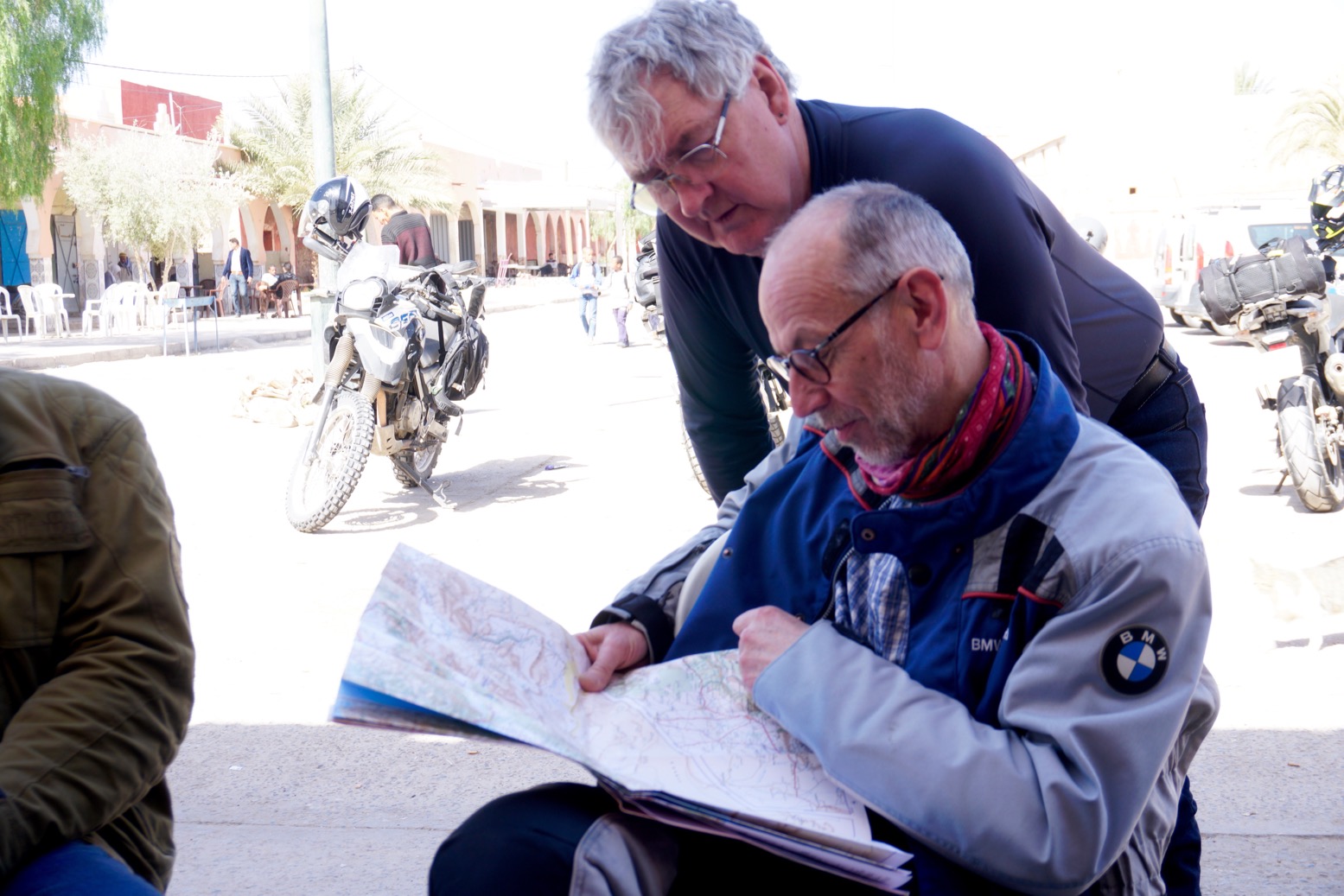

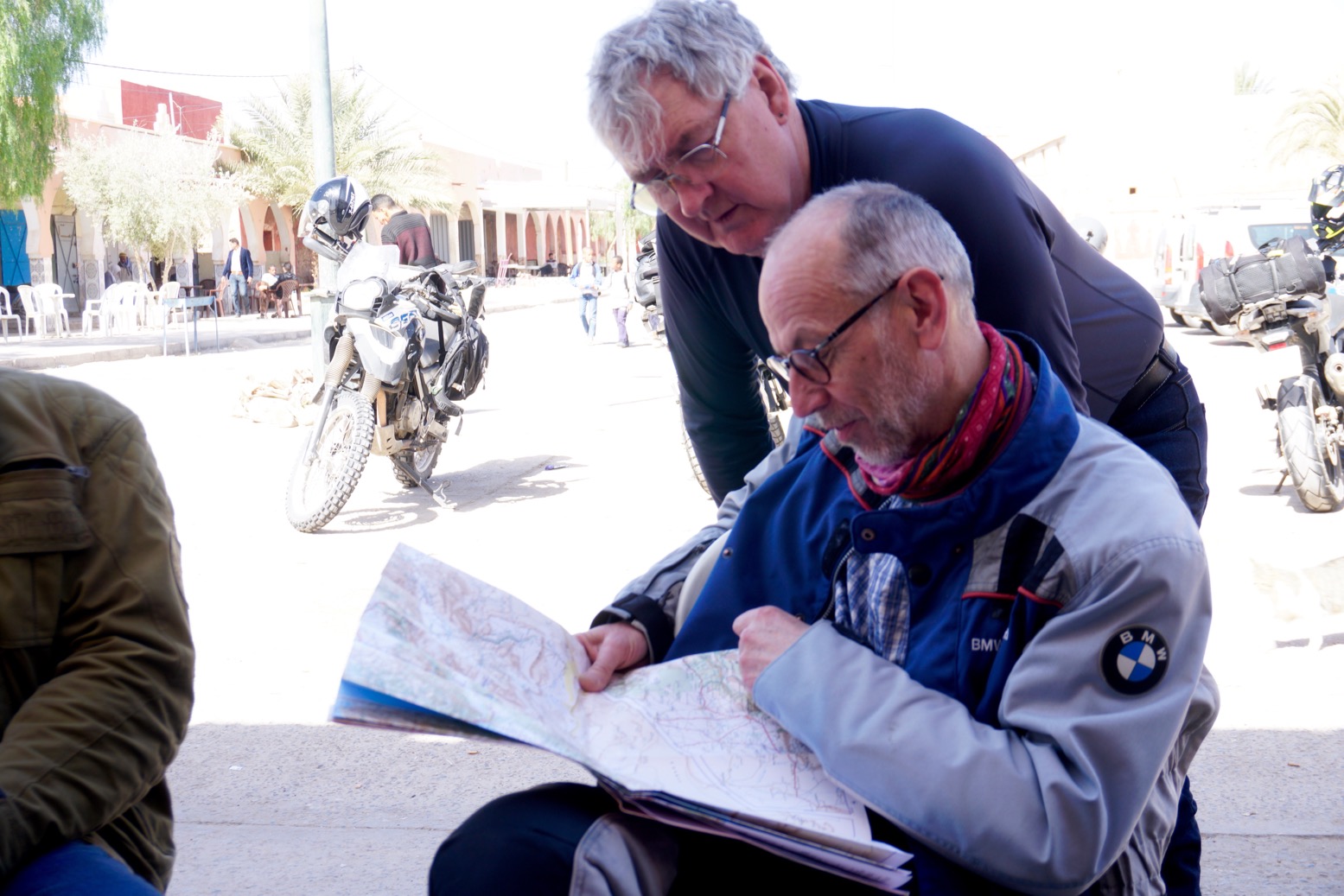

Checking the link route to Map Junction above Ijoukak.

Checking the link route to Map Junction above Ijoukak.

1970s Transit. One of the only vehicle’s I saw today once off the main roads. The other was a Trannie too.

1970s Transit. One of the only vehicle’s I saw today once off the main roads. The other was a Trannie too.

Another photogenic village somewhere.

Another photogenic village somewhere.

Resting outside a village north of Sidi Ouazik, a relocated Reguibat (Saharawi) ends up giving me some meteorites from the Hammada du Tindouf (St Expert mentioned these in WS).

Never knew Saharawi were relocated way up here – 45 families, he said.

I tell him I’m on my way to Reguibat country. About 5 days ride from here to #thedigtree

Sunset at the casbah.

Sunset at the casbah.

Always room for a whaffer thin slice of cake.

Always room for a whaffer thin slice of cake.

Like most people, I was shocked by the brutal murders of the two Scandinavian women camping in the High Atlas in December 2018. Sadly it was another attack attributed to young men seeking to show solidarity with violent Islamist causes.

One assumes the two women were stalked by the perpetrators from Marrakech, and so the attack might as well have happened anywhere once an opportunity presented itself.

Morocco has been largely free of the types of the attacks which became commonplace in western Europe at this time, and yet tourists who’ve long been targets elsewhere in North Africa and the Sahara, are thick on the ground in all the usual Moroccan places because they feel safe. The last reported terrorist attacks were a bomb targeting tourists in Marrakech in April 2011 and a bigger wave of bombings in Casablanca way back in 2003, mostly aimed at Jewish interests. Unlike the rest of the Sahara, to date no tourist has ever been kidnapped in Morocco.

How to be safe in Morocco

As a tourist, maintaining your safety in Moroccan cities is no different to any other unfamiliar place. Hustlers are common in certain areas; traffic appears chaotic; pickpockets exist and cheap hotels can feel insecure. And out of the cities mountain roads may not all be velvet-smooth Alpine super highways. All these issues have long been far greater threats to visitors in Morocco than Islamist violence.

Being a Muslim country does give Morocco an edge to those unfamiliar with Islamic culture, particularly women, but the Islam practised here is a lot less severe than in Saudi or Iran, for example. Read the blue box, left, extracted from my Morocco guidebook. Also read the sensible guidelines given on the British FCO website, to give one example. They spell out all how to be aware of the most common risks.

In a crime sense, the popular hiking area below Mt Toubkal (left) where the women were murdered is not dangerous compared to a big Moroccan city. It is probably its popularity and proximity to Marrakech which make it an easy, adventurous destination.

Occasional unnerving but actually harmless encounters over the years have long led me to advise the following: when wild camping, do so unseen and completely out of sight if possible, and if not then camp close to or in a settlement. This way either everyone knows you’re there or no one does. I give similar advice in both my global overlanding books and would act like this anywhere in the world, just for peace of mind.

In Morocco many have found undisturbed wild camping can be quite hard to achieve. Even in the desert, travellers commonly report someone popping up out of nowhere, usually a curious nomad or villager, or sometimes police checking up on you. It should be understood that in North Africa and the Sahara, camping alone in the middle of nowhere away from other people is regarded by locals as suspicious or odd.

For us Euro-tourists camping has long been regarded as a money-saving adventure, but because hotels and auberges can be so numerous and inexpensive in southern Morocco (from <€5), I’ve long preferred the comfort and security they offer to all the clobber and faffing required with camping, especially if not travelling in a spacious car, or when travelling in the cool season when mountain nights get chilly and drag on for 12 hours. In a cozy auberge you get to meet local people or fellow travellers, eat well, rest properly and recharge your gadgets.

Another practise desert travellers like me have adopted since the deep Sahara became FUBAR’d, is not to share detailed travel plans with strangers or online, especially on publicly readable social media. I don’t do Facebook or Whatsapp, but by all means keep friends and family in a closed group appraised of your movements. In Morocco the reach of the mobile network is far greater than you’d expect, not least in remote rural areas where locals depends on it. A local SIM card costs from €2 which includes €2 of credit. You may need the vendor’s help in setting it up.

No one could have anticipated the appalling murders in the High Atlas any more than crossing a bridge in London, backpacking in New Zealand, visiting a market in Strasburg, attending a Baltic island retreat, or a school or place of worship in the US. Morocco remains one of the few countries in North Africa where tourism continues to thrive despite anxieties about ‘Muslim countries’. It helps sustain the local economy, particularly in rural areas where the true level of poverty is much greater than it looks. Don’t let this tragic event unsettle your plans to visit a wonderful country, any more than any of the other places listed above.

The N9 is the main highway crossing the High Atlas between Marrakech and Ouarzazate, topping out about halfway at the 2260-m Tizi n Tichka pass where a superb range of clay souvenirs and vibrantly coloured ‘gems’ are permanently on display. Being the main road, traffic can be relatively heavy and slow, and the hundreds of bends make cycling a bit stressful and overtaking tricky in a vehicle, especially when climbing or away from the recently widened ‘race track’ which uncoils a few kilometres north of Tichka (below). But even on this recently improved section, landslides and subsidence are already taking their toll.

The N9 is the main highway crossing the High Atlas between Marrakech and Ouarzazate, topping out about halfway at the 2260-m Tizi n Tichka pass where a superb range of clay souvenirs and vibrantly coloured ‘gems’ are permanently on display. Being the main road, traffic can be relatively heavy and slow, and the hundreds of bends make cycling a bit stressful and overtaking tricky in a vehicle, especially when climbing or away from the recently widened ‘race track’ which uncoils a few kilometres north of Tichka (below). But even on this recently improved section, landslides and subsidence are already taking their toll.

Short of the usual floods and storm damage, both the diversions outlined below are doable in a regular 2WD rental car, on big motorcycles as well as sturdy bicycles.

On the warmer, south side of Tichka, the alternative route (right) via Telouet was well known, even before it became largely sealed a few years ago. It starts just 4km south of the Tichka col, where the final roadworks on the P1506 are nearing completion on the 20km to Telouet with its famous Glaoui kasbah.

From here the P1506 soon drops off a plateau to follow a long, oasis-lined ravine (below) all the way down to the Aït Benhaddou tourist trap, rejoining the N9 10km later at Tazentout, 23km west of Ouarzazate.

On the north side of Tichka, road widening disruption has currently spread down the valley over 17km north of Tadart, the first village below the col. But once you get to Zerkten village, signed and 33km below Tichka by a red and white telecom mast, there’s an easily missed side road to the west. See map above.

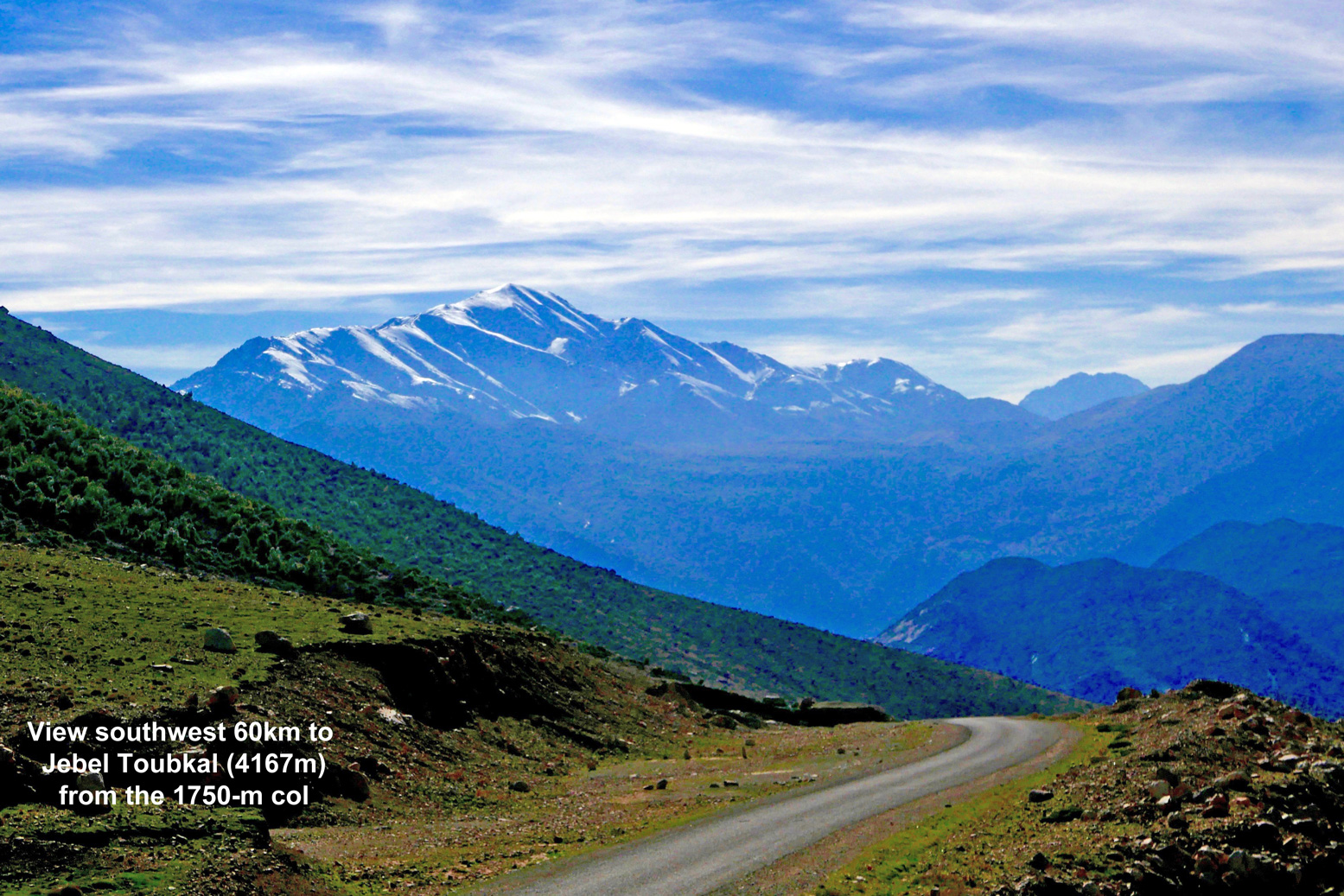

As pictured below, it leads steeply 6km up to a 1750-m col to an impressive view 60km southwest to the 4167-m mass of Jebel Toubkal. It’s one of the few points on a sealed road that gives a full view of North Africa’s highest mountain (picture, top of page).

From here the road drops down through apple orchards recalling the Aït Boumengueze valley further east, below the Mgoun massif (MH18. MH19).

It levels out along the Oued Zat at the town of Tighoudine in the Oued Zat valley where, in late November, you’ll detect the strong aroma of olive oil being produced in roadside presses (right).

The side route rejoins the N9 after 35km, just before a green Winxo fuel station on the north side of the road, 46km from Marrakech.

Part of the Sahara A to Z series

High up on the side of a remote High Atlas valley is an engineering marvel – hewn through the cliff face a spiral tunnel manages to curl down through the rock and emerge underneath itself.

I was told about this curiosity in 2012 by the chap at the cozy Chez Moha auberge (right) in Aït Youb while researching the second edition of Morocco Overland. Riding a BMW F650GS, I followed his directions with the usual route-finding issues and then, beyond the last village, hacked up a stony disused track to the 2250-m (7340′) Tagountsa Pass. From the cliff edge I recall the timeless view stretching east up the Plain d’Amane valley towards Rich, pictured below and on p128 in the current book. A short distance later I spun through the tunnel and rolled down a series of switchbacks back to the valley floor and a tasty tajine back at the auberge.

Spiral tunnels have been a long-established solution to constricted route building challenges across mountains. You could even say that your typical complex freeway intersection where the road winds back under itself to change direction tightly is the same thing in flyover form. But you must admit that hacking out any type of tunnel – let alone one where there’s no room to dig out a regular switchback – is an impressive task.

Not for the first time on this website, I’m able to benefit from research of Yves Rohmer (right) on his always fascinating collection of old Saharan curiosities at Saharayro, including the Tagountsa tunnel. Viewed on Google Earth, the big picture is more vividly rendered setting View > Historical Imagery back a few years.

Even then it’s hard to visualise what’s happening until you look at the old plan, right. You can see the anticlockwise descent of the bore and just work out that it starts with a short separate concrete bridge over the lower mouth of the tunnel. The daylight streaming down the gap can be seen in the image repeated on the left (and as a slim shadow in the round inset, above)

Built in 1933 over a period of just three months by some 3000 labourers from local and French regiments, few realise that at this time the French were still fighting to subdue renegade Berber tribes in the mountains of Morocco.

As you can see on Yves pages, the engineers, sapeurs and legionnaires passed their spare time commemorating their achievement by engraving regimental emblems in and around the structure. I was told the motivation for all this effort was to enable a secure, high transit of the valley, so avoiding protracted Berber ambushes at the narrow Imiter Gorge (left; ~KM70) with it’s Mesa Verde-like dwellings.

The same crew probably built the better known 62-metre Tunnel de Legionnaires five years earlier at Foum Zabel now on the main N13 highway north of Errachidia. A plaque there boldly states:

“The mountain barred the way.

Nonetheless the order was given to pass…

The Legion executed it.”

The Tagountsa tunnel the Legion helped build is at KM102 on Route MH13 in the book, though if you reverse the route it’s only a 10-km off-road drive off the Rich road just east of Amellago, turning north onto the dirt at KM113. Depending on storm damage, an ordinary car or a big bike should manage it, but note that you’ll be negotiating all those hairpins on the Google image above. From the west side (as Route MH13 describes the loop) it was a rougher and slightly more complicated ride on the BMW up to the pass.

Perhaps because trains can’t negotiate hairpins or climb very steep grades, it seems that spiral or helicoidal tunnels have been a much more common feature on mountain railways than roads, particularly in the Rockies.

Norway’s Drammen Spiral (left), some 50km southwest of Oslo is a notable example, dug we’re told, as an alternative to disfiguring effects of open quarrying on the landscape back in the 1950s while at the same time producing a revenue-producing tourist attraction in the process.

Updated December 2025

Trans Atlas: J2

Talat n Yacoub (Ijoukak) > Ouneine basin > Ouaougdimt valley > Aoulouz • 88km

Last run October 2023 – CRF300L

Following the September 2023 earthquake, the steeper north slope of this track is almost immedaitely blocked and remains unused. To get to Ouneine take the bypass and cut back west via the road or the MH212 link route.

Description

High Atlas crossing parallel to the nearby Tizi n’ ‘Test which peaks at the 2200-m Tizi n Oulaoune (30.940222, -8.125111), following a steep climb: some 500m in 8km after leaving the road SE of Ijoukak (right).

You may find the looser parts of this climb a struggle in a 2WD or on a heavy, wide bike, but this was not the case on 2022 in a 4×4. It’s probable that local 2WD vans only do it downhill (northbound) to Ijoukak. Track immediately blocked by post-earthquake debris (below; 6 months later) and remains abandoned.

In 2022 the track was rougher as it rolled down to the Ouneine basin and the P1735 whose extension eastwards to Igli on (J3) is now sealed. Keep right at the fork with an illegible sign. At the bottom just before it joins the road you have to detour south around the boundary fence of a new small mine,

Once in the basin carry on SW along the P1735, and at Sidi ali ou Brahim swing sharp left off the road, cross the stream and follow the Ouaougdimt valley 24km SE (not fully shown on most paper maps) to join the road coming down from Aguim on the N9 Marrakech–Ouarzazate road.

Or, if you’re in a rush or heading towards Taroudant, at Sidi ali ou Brahim carry on 23km south on the ever-bendy P1735 to Sidi Ouaziz (fuel) on the N10. Otherwise, it would be a shame to miss out on the scenic Ouaougdimt valley stage, as it rises onto a terrace high above the valley floor.

Mapping

Parts of the route are just about legible on paper maps, least badly on the inset ‘High Atlas’ panel on the Michelin. But none show the full Ouaougdimt valley route. It’s all on Google and the OSM/Garmin digitals.

Off-Road

The climb up to the 2200-m Tizi n Oulaoune pass from KM11 starts a steeply but is now blocked. From the pass the gradient eases off with great views doiwn to the basin while you’ll find the Ouaougdimt valley stage no harder than anything you’ve just done. Carefully ridden, a big bike might manage the loose hairpins; so could a 2WD with low first and clearance, though as always, these mountain tracks require concentration. On an MTB it will be a slog if not a push up to the Tizi n Oulaoune, followed by a rough freewheeling reward to the basin and no more huge grades thereafter. Bikes might have more fun following J3 to the high P1735 road, turning left or right.

Route finding

Easy enough. We winged it just by studying Google satellite imagery beforehand, jotting down some distances between junctions. That’s now all listed below. Download the kml file.

Suggested duration

Half a day will do you.

Route Description

0km (88) Talat n Yacoub fuel station (village destroyed but still serving) on the N7 Tizi n Test road. Head north to Ijoukak village.

3 (85) Pass through Ijoukak, cross the bridge and turn immediately right up the side road now thronged with relief tents. Soon you’ll pass Houssain’s agreeable mountain lodge (repaired; reopened). Huge boulders have fallen on the road.

11 (77) At the fork before a village turn right, drop down over a bridge and carry on. Soon there’s a sign right: ‘Ouneine? 24km’. The 500m climb to the pass begins. (Ahead, MH21 continues). To reach Ouneine take the J2 bypass and take the road, or link track which comes in to Map Junction below.

19 (69) Tizi n Oulaoune 2200-m high point with views of Toubkal (4167m) 20km to the northeast. The track now eases off as it descends.

23 (65) Fork with sign (photo above: ‘Map Junction’). East at this fork is a rough track (MH212) which in 9km joins J2 to Igli. Keep right (south) to continue descending to the Ouneine basin visible to the west. At a small mine work your way round the fence to the south. to rejoin the track. Eventually, at a junction around KM35 you join the P1735 road which goes E towards Igli/Iguidi over a 2500-m terrace. This is a spectacular high mountain road (J2).

Meanwhile, the P1735 crosses the Ouneine (shops and cafes) basin SW and threads through a small pass back into the hills.

54 (34) Sidi ali ou Brahim. The tarmac carries on 23km to Sidi Ouaziz (fuel) on the R110/N10 but you turn sharp left here, drop down to the stream and up the other side. The track is initially a bit eroded and loose as it climbs to the first village, but that’s why they invented suspension. It then eases off as it rises above the valley on a terrace (right) with great views down to the villages below. You could be in the Cevennes or the Pyrenees, but you’re in the High Atlas. It could be worse.

78 (10) Join the tarmac (J4) by the reservoir. Turn right (west).

83 (5) Roundabout on the R110/N10.

88 Aoulouz fuel stations.

Trans Atlas: J3

At the ‘Ouneine’ turn-off for the blocked track up to Tizi n Oulaoune, carry on southeast on tarmac for a few km until it ends at a village (green mark on map above). Keep going along an easy piste rising up the valley and past a couple more villages all surrounded by relief tents in 2023. Just before one village keep right (downwards); sharp back left leads up to who knows where. Your route climbs to meet the end of the J2 link track close to the Ouneine-Igli tarmac.

Turn left then at the tarmac nearby it’s left up to over 2550m then a long wind down to Igli/Iguidi (hotel/cafe) on the Aquim-Aoulouz road J4.

From here carry on south then west down the valley and turn left at a sign to cross below the dam wall (long term roadworks) and wind your way up to up to Askaoun (KM120) then 45km down to Taliouine.

Total 170KM, fuel to fuel.

I did versions of this route three times in November 2022 with a lunch in Igli. A great ride with a dizzying number of bends in one day.

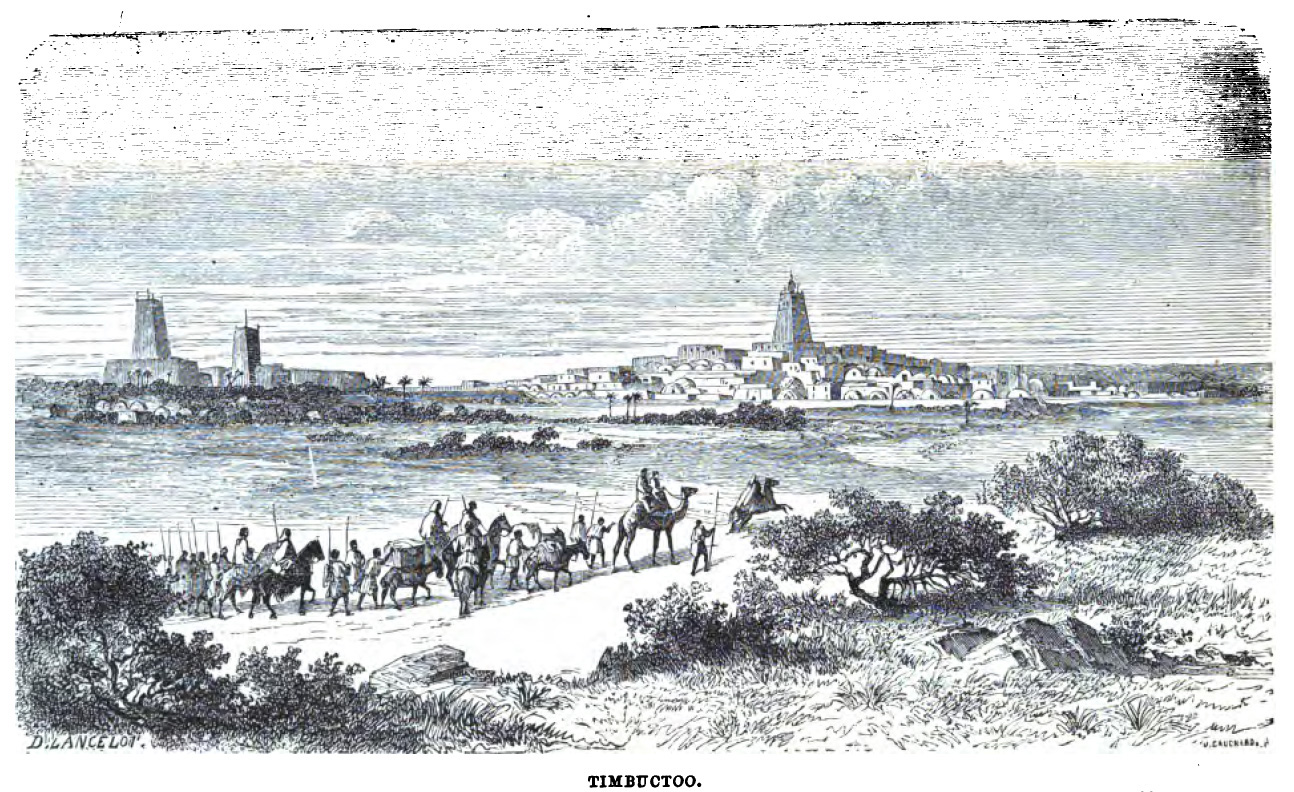

… I had reason to believe that there existed, in the Western Sahara, a vast depression which might be submerged by the waters of the Atlantic, thus opening a navigable way to [Timbuktu]…

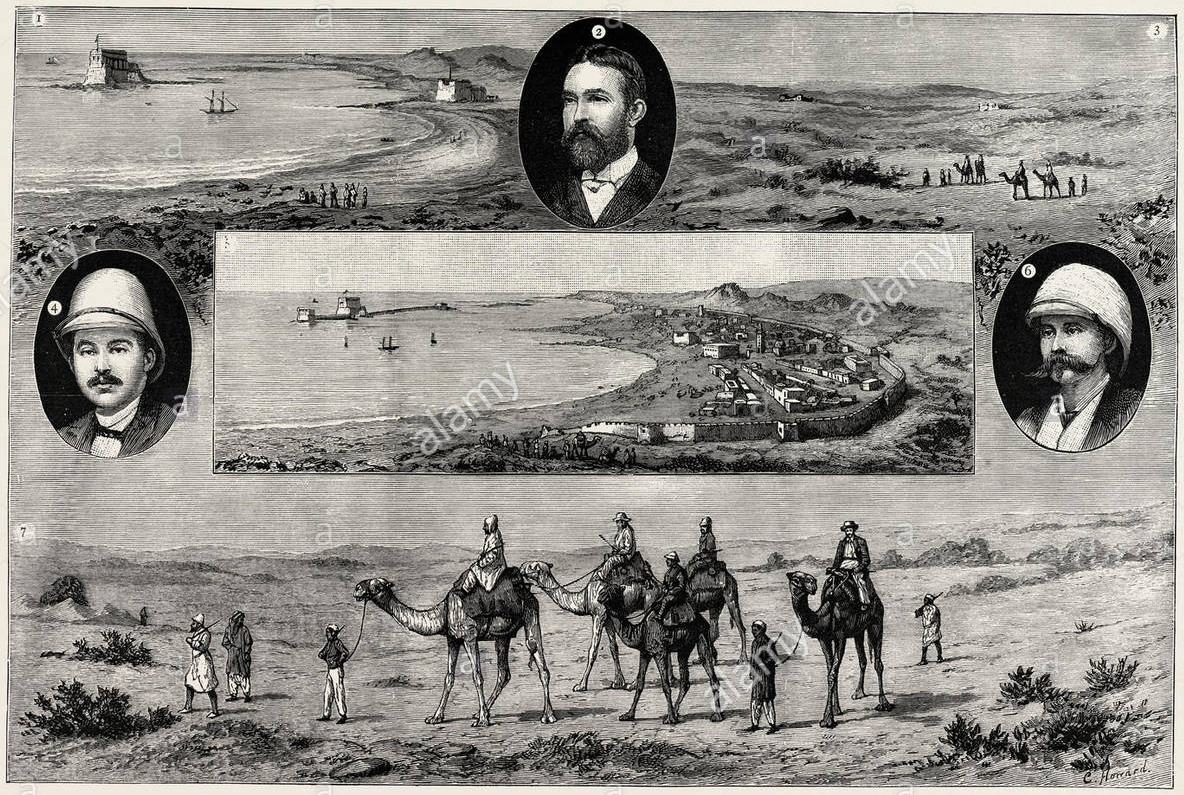

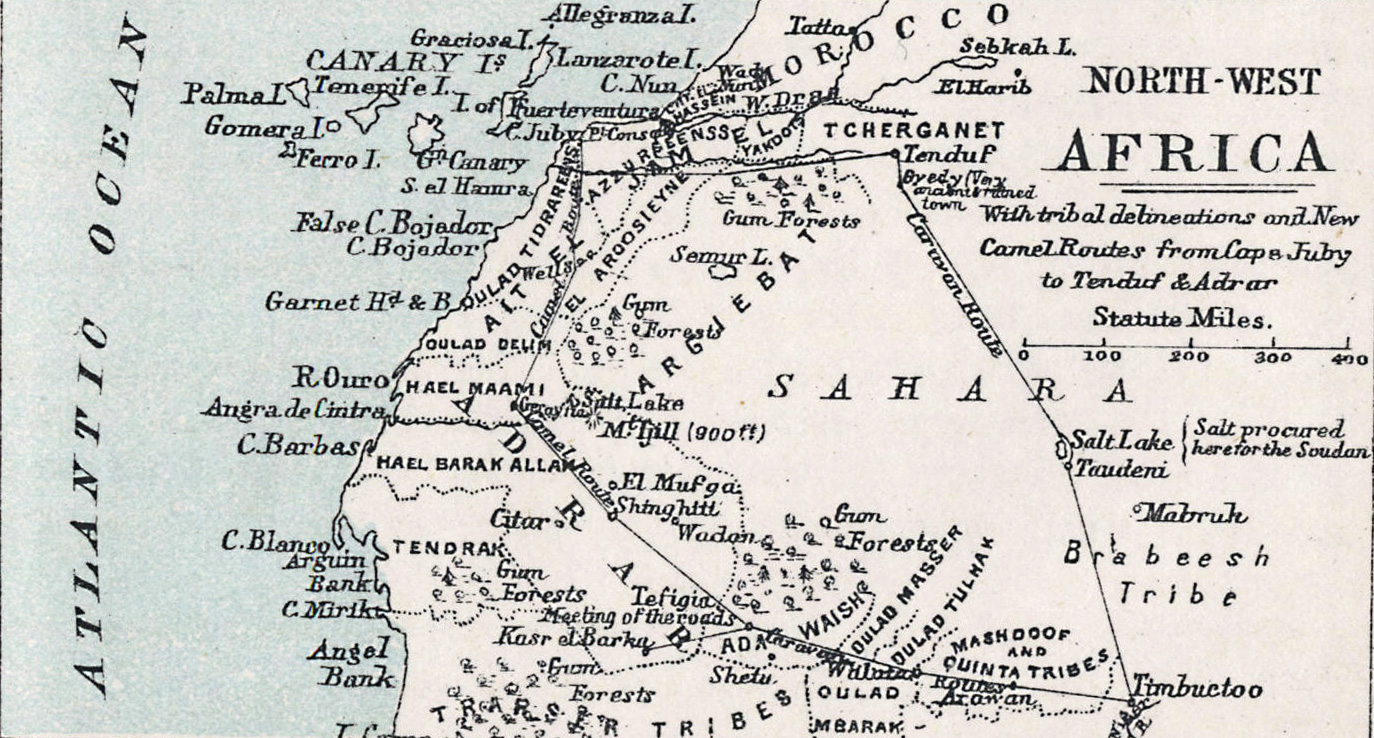

Visit Tarfaya on Cape Juby and just offshore you will see the curious Casa del Mar fort, beyond the St Exupery monument. Port Victoria or Mackenzie’s factory are other names for the trading post of the North West Africa Trading Company, established by Scotsman, Donald Mackenzie in 1882 during the ‘Scramble for Africa’.

Mackenzie’s venture hoped to capitalise on the recent westward swing of the trans-Saharan caravan trade emanating from Timbuktu, by intercepting caravans before they reached the terminus at Wadi Noun (near today’s Guelmin).

In fact, in a decade or more the NWAT Co barely covered its costs after compensation was finally agreed against an earlier raid and to abandon the post in favour of the Moroccan sultanate.

It reminds you that colonisation at the time wasn’t purely a state affair, where armies marched off to conquer distant lands and bring back the spoils. Ahead of them strode adventurer-entrepreneurs with funds raised from venture capitalists and who gambled everything on striking it rich. It was their reports, or better still, securing a government charter to supply a commodity or service, which preceded more cautious colonisation, very often spurred by other European rivals nosing around for an as yet unclaimed slice of the cake.

It’s hard to find out much about Donald Mackenzie, but in 1877, a few years before he set up the North West Africa Trading Company, he had a far more radical idea to capitalise on the trans-Saharan trade.

He proposed nothing less than flooding the interior of the Sahara from the Atlantic so that, with the addition of a few canals which had proved so successful in Britain prior to the age of rail, ships could sail directly to Timbuktu and the Niger river in a matter of days, avoiding the arduous overland journey of weeks. As a side benefit the flooding would ‘green’ the Sahara, enabling agriculture to thrive across the wind-blown sands.

This was the era of grand engineering projects like the Suez Canal (completed 1869) and the Panama Canal (first serious attempt 1881). A canal to the trading heart of West Africa could be a similar commercial coup.

It’s hard to think what gave Mackenzie this idea, other than conflating lurid traders’ descriptions of El Djouf (left) with the small depressions or sebkhas found near Cape Juby. The biggest of these is the Sebkha Tah, some 55m below sea level and just 15km from the Atlantic, but still no bigger than Malta. For some reason he believed that the vast El Djouf (part of the million-square-kilometre Majabat al Koubra or ‘Empty Quarter’) was one huge depression which had been connected to the Atlantic via the Seguia el Hamra or some such, but had become cut off and dried out.

Mackenzie had never actually travelled in this area (other than a camel tour up to Port Consado (present day Khenifiss) and down to Layounne during the NWAT Co era (map above and right) but had read of other larger desert depressions in Tunisia and Egypt, similar to those near Cape Juby. All these basins held seasonally dry salt lakes which may have suggested that flooding was plausible. He believed an inland sea the size of Tunisia or Oklahoma would soon be formed, paving an inland seaway to Timbuktu.

Mackenzie diligently read up on all your great 19th-century Saharan explorers: Barth, Rohlfs, Caille, Duveyrier, Clapperton, and in 1877 published an exhaustive proposal [available online] to ‘The Presidents and Members of the Chambers of Commerce of Great Britain‘ stressing ‘the importance of holding commercial intercourse with the interior‘.

Vividly detailing at third hand the riches, economy, geography and ethnicities in this corner of Africa, he firmly believed his northern route reaching down into the African interior was the key, avoiding the disease-ridden equatorial jungles and pagan tribes further south in favour of the more sophisticated vestiges of the West African Islamic states. Under his proposal, land distances for the annual camel caravans from Timbuktu would be halved, with Cape Juby just nine sea days from Britain. De Lesseps himself, the force behind the Suez and original Panama canals, supported the idea of Saharan flooding, believing a side benefit would somehow improve the European climate while greening the desert for agriculture.

Mackenzie also thought that trade and communications would help liberate the sub-Sahran population from the slave trade. And this wasn’t just a ploy to appeal to investors’ morals or religious beliefs – Mackenzie’s later work in East Africa long after the NWAT Company dissolved suggested he was always a genuine abolitionist.

Mackenzie also thought that trade and communications would help liberate the sub-Sahran population from the slave trade. And this wasn’t just a ploy to appeal to investors’ morals or religious beliefs – Mackenzie’s later work in East Africa long after the NWAT Company dissolved suggested he was always a genuine abolitionist.

According to his upbeat proposal (is there any other kind?) Mackenzie has it all worked out: do a recce to get the tribal chiefs on board at Cape Juby and Timbuktu, locate the channel in El Djouf and unplug that Atlantic cork.

I have no doubt of the ultimate achievement of this project, he wrote in the proposal’s introduction. But investors seemed less keen and, were it even possible, you’d think by creating a shallow, hyper-saline lake, the only thing that would grow would be salt crystals. The fact is the interior of the Sahara, including the dune-filed expanse of El Djouf spanning the Mali-Mauritania border, is a low plateau some 3-500 metres above sea level. Someone ought to tell Conde Nast Traveler.

Mackenzie had slightly less difficulty finding investors for Port Victoria a few years later, and decade or three after that, Jules Verne fictionalised the idea of a flooded Sahara in his last published book, The Invasion of the Sea, set in Tunisia.

Part of the occasional Sahara A to Z series

Hang around long enough and you’ll get the full set

Pictures from Emile Leray’s website [dead link] and the web

In July 2012, a couple of years before fake news had become a thing, online media tripped over itself to syndicate a compelling Saharan survival story evoking the gripping 1965 desert drama, Flight of the Phoenix.

Then, five years later a video appeared on youtube (below) where the aged and batty-looking French adventurer again recounted his incredible desert caper.

Back in 2012 full details and motivations were skimmed over, but the story goes that in March 1993, 43-year-old Frenchman Emile Leray set off from Tan-Tan near the Moroccan coast to drive his Citroen 2CV east to Zagora – more or less Route MW2 from my Morocco guidebook (below), followed by MS8 from Tata.

But with the Polisario ceasefire just 18 months old and frequently being broken, at Tilemsen the Moroccan army stopped him from continuing south towards Mseid, the former Polisario front line. Leray turned back towards Tan-Tan, but not before incurring some animosity from the army by refusing to give a soldier a lift back to town – a common request at remote Saharan checkpoints.

Just west of Tilemsen, Leray ‘had an idea’. He decided to circumvent the checkpoint to the north (see MW1 KM22), and rejoin MW2 eastwards. But once on the piste (or ‘off-piste’, as claimed) one of the 2CV’s suspension arms broke after hitting a hole too hard. With ten days’ provisions on board but reluctant to easily walk-out and leave his car vulnerable to theft, he decided to strip his crippled Citroen and rebuild it into a rudimentary motorcycle, then ride out as if nothing much happened. The unusual powertrain and suspension arrangement of a 2CV makes such a conversion plausible.

The way the story was initially reported in English – using images shot later in a quarry (above) – Saharan know-alls like myself were initially sceptical. If it really happened why not just walk back half a day to the road?

I researched the yarn more closely for my Morocco guidebook and came across his own account published in a 2CV enthusiasts’ magazine a decade after the events. A faint ring of truth came through. Perhaps he did build the 2CV bike, but not in quite the circumstances he claimed.

As the TV show, Mythbusters proved for themselves, his contraption was barely rideable (left) and within a day of leaving the rebuild site, Leray says he was caught by a patrol while camping in the desert and instructed to lead them back to the car’s remains to corroborate his story. Ironically, he goes on to claim (with convincing documentary evidence) that he ended up paying a 4500-dh fine (about €450) for driving a vehicle which did not conform to the one he originally imported to Morocco a few weeks earlier, even though he’d taken pains to tack on his ‘Steel Camel’s’ original license plate.

I believe the 2CV bike was indeed built in the desert, much as Leray claims, but he set out from France with the explicit intention of performing this task. Otherwise he’d have walked out like any normal person in a similar situation.

His claimed unease about leaving his stricken car doesn’t ring true, let alone the spontaneous idea of making it into a two-wheeler. Tellingly, in 2006 Leray went on to build a ‘2CV boat’ in Mali. He clearly likes mucking about with 2CVs. Fair play to him!

Below is the translated story as posted on Leray’s website so you can form your own impression. Bear in mind there’s no reason to believe this account, but it may have been the original version.

In March 1993 Emile Leray set off to follow a route from Tan-Tan to Zagora. He left Tan-Tan with the required reserves of fuel and provisions as well as tools to keep his old 2CV on the road. As soon as the Royal Gendarmerie arrives, they strongly discourage him from continuing further because the zone beyond Tilemsem is prohibited, following new developments in the conflict between Morocco and Western Sahara. Emile must obviously turn around and the soldiers are asking him to take a passenger back to Tan-Tan.

Analyzing the situation, and seeing his project thwarted, Emile claims an insurance problem that does not allow him to take passengers, arguing that his 2 CV is already very loaded. He knows full well that in Africa it’s seen very badly to not take soldiers aboard his car in these circumstances. He claims naivety and misunderstanding in adopting the attitude of a tourist not familiar with local customs.

Emile then returns to Tan-Tan under the disgruntled and disapproving look of the soldiers. He starts off at a good pace as he’s afraid he will be followed and he wants to remain out of sight of those whom he has just left. His plan is to bypass the area off-piste and return to his original direction … After a few kilometres he leaves the track to the north and traverses uneven and rocky ground.

After bouncing more strongly, the car jumps and brutally strikes a rock. He must stop because the 2CV does not respond very well. And for good reason – a folded wheel arm and broken spar …

Émile organizes his encampment around the broken 2 CV and reflects on the situation. He is a few miles from Tan-Tan which he could reach on foot, but he runs the risk of leaving is car certainly in bad point but still able to attract theft, including its equipment. In the desert nothing is permanently lost, especially for the one who knows where to look.

He has enough food and water so makes a decision which is to say the least, amazing: from his wreck, he will build a two-wheeled machine! One by one he carefully considered all the technical obstacles that this entails, and this master of African bush mechanics has all the tools and the elements to succeed in the task.

The next morning he began to dismantle the 2CV, first removing the body which he will use as shelter against the cool nights and sandstorms. Having no long-sleeved shirts, against the burning sun he makes sleeves from a pair of socks. With what remains of the car, Emile Leray will try to build a motorcycle. Overnight he mentally reviewed all the stages and difficulties involved in this rather crazy project … A project that he had probably imagined for a long time but without having had the opportunity to realize it.

The wheel arms (to be removed with a hacksaw) are nested upside down on a reduced chassis of the front and rear side rails. The engine and the gearbox are then placed on the chassis in the center. Space should be reserved for the battery and the fuel tank and to keep space for luggage without neglecting the layout of the steering system.

The most surprising thing about this 2CV motorcycle is the transmission. It was inspired by the Vélosolex moped idea (right): the engine drives a drum which in turn turns the tyre by friction, and which, by the laws of physics and mechanics, obliges it to roll with the reverse. Disassembling the gearbox to reverse the differential would have been too risky in this universe of sand …

It seems unthinkable to assemble this machine in the desert without the help of a drill and welding station. All parts were assembled by screwing. When drilling, it will be done in the African way: the piece of metal is folded to 90 ° to form an edge. At a fixed point this edge is weakened by a hacksaw or round file. At the limit of the drilling, the piece must be replaced flat to perforate the filed point with a hammer or a needle. The assemblies were made as much as possible according to the original holes of the chassis or engine-box unit.

The rest is only a matter of time dependent on the quantity of his provisions. Émile believes he must spend three days building his bike – in reality it will take twelve …

There was a great deal of uncertainty to carry out this project and it wasn’t so easy to realize as one might think. The possibility of failure remained present throughout the adventure, giving some anguish to the stranded mechanic.

The 2CV motorcycle was obviously not conceived for the sake of comfort, it is a rather secondary notion that was not imperative in what we can call the specifications. The prototype has therefore not benefited from some desirable improvements. It should be noted that, for example, the exhaust is free, so the nose and the ears are affected greatly by the engine’s gases. The bike does not have a brake, nor does it have foot rests which allow some control of the trajectory with the feet, because the craft lacks stability. On the first test the bike fell over, causing a great scare to Emile, who almost found himself crushed under his 200-kilo machine.

The arrangement of the clutch and accelerator controls were particularly tedious. It was necessary to dismantle, adjust and reassemble the parts for optimum operation. Similarly, the tests were punctuated by frequent falls. To lift the two-wheeled steel camel proved particularly physically difficult … All these circumstances contributed to prolong Emile stay in the desert. The final day was be spent adjusting and testing and cleaning the bivouac site.

It was an occasion to immortalize the moment thanks to a small camera with the trigger connected by a long wire. Émile poses in the middle of a place that in March 1993 was the theatre of his unusual feat.

He leaves the next afternoon leaving the parts that he will not use in the body shell of the 2CV. He takes with him the rest of his food (more than a litre and a half of water), the bed, the tool box, not forgetting maps and compass. A small foam mattress and a towel sewn together will serve as a tent.

After a bumpy ride and a few stops for mechanical improvements, he encamped and slept at the edge of a track. In the night, he is awakened by three soldiers in 4×4, one of which immediately recognizes the “tourist” of Tilemsem. Very irritated to find him in the forbidden zone, he strongly doubts Emile Leray’s explanations; an accident followed by the transformation into a motorcycle. Intrigued by the machine, but totally incredulous, the soldier demands to see the carcass of the 2CV to have proof of this incredible story.

The officer puts an armed guard by the tent and the motorcycle, then embarks with Émile in the 4×4. After an hour of research in the dark, the remains of the 2 CV cannot be found. Back at the camp, Émile is allowed to rest near the motorcycle until dawn, guarded a hundred meters away by the military in their 4×4. The next day, the carcass was found and the soldiers relax. Émile will learn later that his interlocutor wanted to recover the abandoned pieces for his brother-in-law …

In the early morning, Emile was ordered to take his motorcycle back, and ride in front of the 4×4. The convoy sets off slowly towards Tan-Tan but several falls seriously annoy the soldier, pestering against this unstable machine. Eventually the soldier calls by radio for another 4×4 to come to recover the 2CV motorcycle.

Arriving at Tan-Tan on April 6th, things get complicated with a lot of bureaucratic hassles. At the provincial governor’s office, a report is drawn up, as well as by the Royal Gendarmerie. The vehicle is impounded

Emile has the disagreeable surprise of learning that he has to pay a tax of 4500 dirhams. He is very unhappy because the customs officers had spoken to him on the eve of mere formalities. The vehicle is regarded as dangerous and no longer corresponds to the description of the registration documents.

“Delay in importing a non-conforming vehicle” is the charge, and by paying the fine he can regain his freedom and recover his contraption, but not be allowed to drive it.One could say a lot from this misadventure about the complicated relations between Africans and Europeans on the issue of money ...

The next day Emile is summoned to sign the forms to exit the territory, and leave for France. He thinks he should come back as soon as possible to get the bike back, but by then he must find a place to park it. There is no question that he leaves her in the pound, it may cost him dearly, and the place is not guarded. A customs officer who is more sympathetic than his colleagues offers to take the steel camel home while waiting for him to return to Morocco.

A month later Emile made the 3500-km journey between Rennes and Tan-Tan with another 2CV to pick up his motorcycle, now dismantled in three parts …

Since then, the steel-motorcycle camel has enjoyed the honors of the press and participated in a few events such as the Aventure and the Inventors of Rennes, the fiftieth anniversary of the 2 CV in Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, Without forgetting the Motards have heart.

Émile returned several times to Africa, and in 2006 took a new opportunity for the Doctor of African mechanics to exercise his transformational talents on the steel camel [below]…

For more information: full story and technical details in 2CV Magazine March-April 2003.

In 2006 Leray went on to build a 2CV boat in Mali. He clearly likes mucking about with 2CVs!

In 2006 Leray went on to build a 2CV boat in Mali. He clearly likes mucking about with 2CVs!Updated January 2024

Now only 2 + 10km of piste remains, but plenty of gravel and broken tar

In 2017 Moroccan road builders completed a new High Atlas crossing. I heard about it too late to describe fully in the 2017 edition, although it is mapped on page 110.

I got to ride the route on a 250 just as the book was published in October 2017, and again about a month later southbound in a 4×4. Now it’s a straightforward drive once you find the start points, doable without much of a description or GPS.

Northbound, all you need to know is:

1. Pass through Alemdoun village and stay on the tarmac and first right over the first pass. Southbound, just east of Tabant turn right (south) over the ford for the easy 17-km climb to the Ait Imi pass.

Fuel

Aït Bouguemaze end, the nearest fuel is either Azilal, 79km to the north via MH17 – a fabulous drop from the pine forests. Or stay on MH18 west to Demnate; 83km – about 90 mins of near-constant bends. Also ‘Ouaoui‘ further north via the Cathedral cliff. You can also buy fuel by the litre from shops in Alemdoun and Tabant and other small towns.

One time at Amelgag we chose the gorge route (right) instead of the climb over the pass to Allemdoun, a great diversion (and the original route) which is still used by local Merc taxivans. Coming north, turn off right at the bend as you enter Amejgag village and wind your way north through the village to the gorge.

The sealed route takes you up over a 2350-m ‘Amejgag Pass‘ (KM50) before dropping down to Ameskar and joining the gorge route (KM56). Now the steep climb begins to the 3042-metre Tizi n’Ait Hamad (~KM65). From the top of this pass (left; telecom tower; bloke in a hut) Jebel Mgoun summit (4071m; second only to Toubkal) is a 16km walk to the west.

You descend from the Ait Hamad (above), climb an intermediate pass then descend into the valley of the Mgoun river, bypassing some remote villages around El Mrabitine. Cross the Mgoun stream (KM83) and climb less steeply on dirt for 10km to the Tizi n’Aït Imi (2898m; ~KM98). At the top Aït Bouguemaze valley lies 20km below.

Busy Tabant village (KM117) has shops and basic bap cafes before you join MH18 (if heading west). As the whole area is popular with trekkers, there are several auberges hereabouts.