ALGERIA

Lonely Planet, 2026 336pp £14.99

Buy discounted on amazon

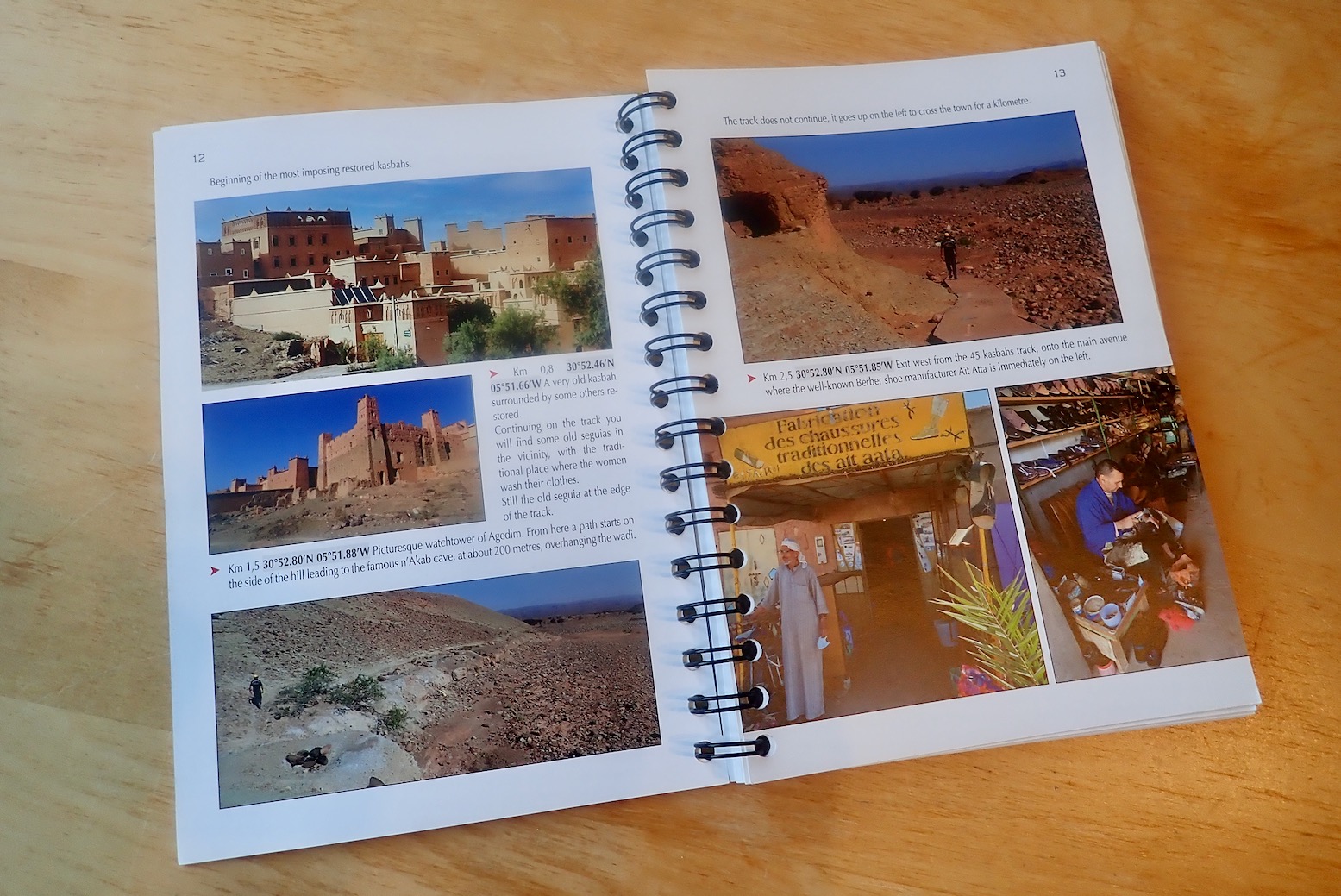

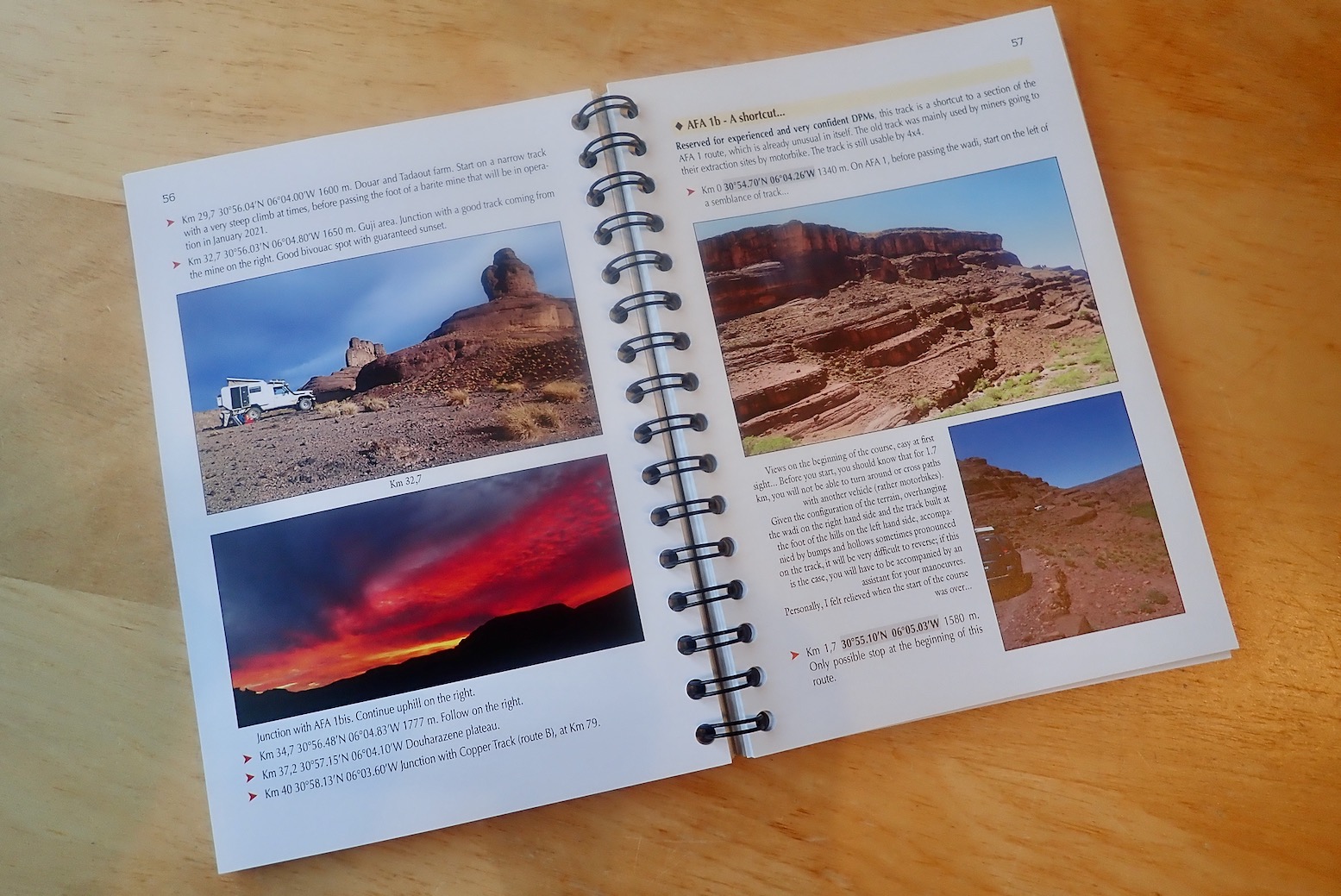

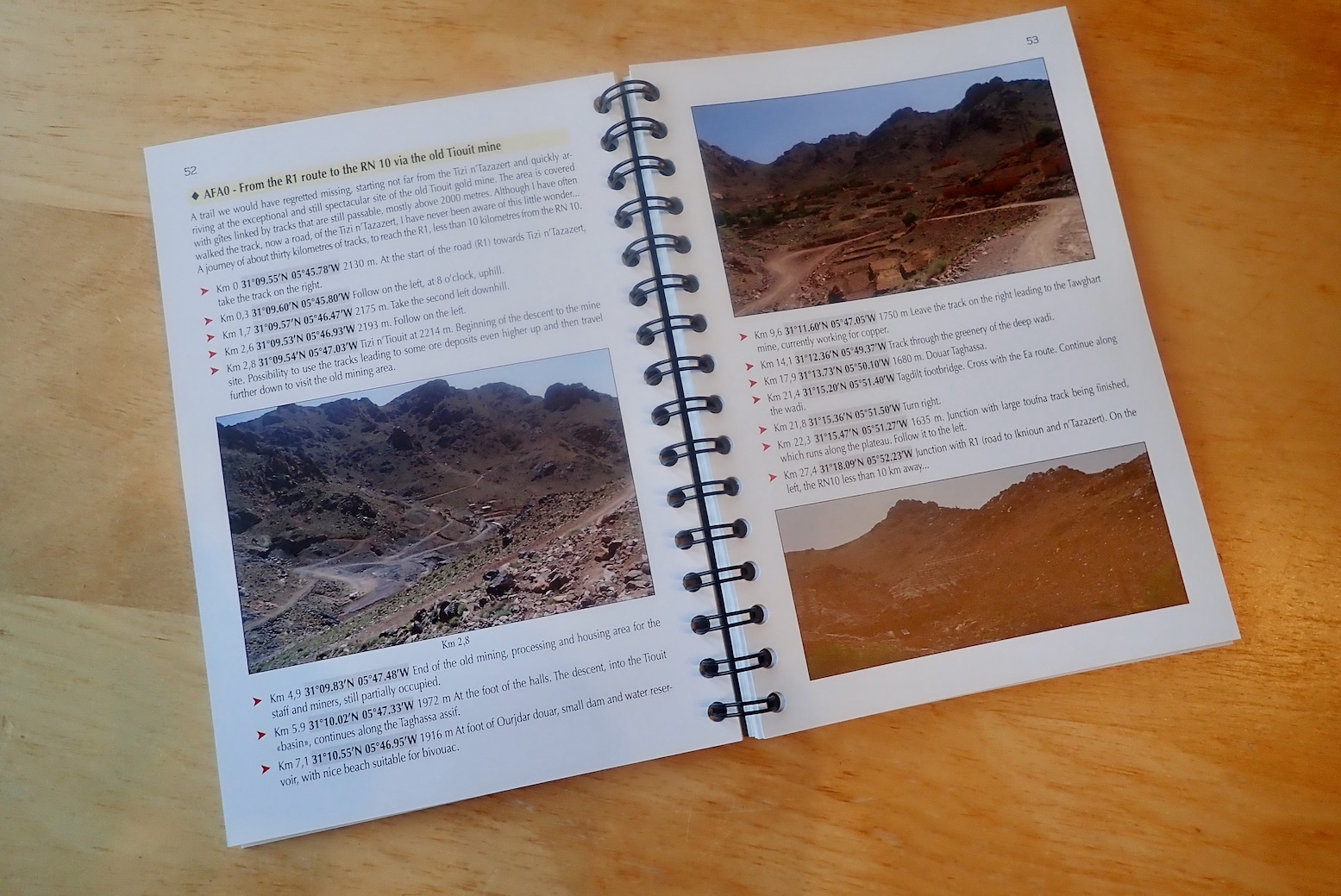

Eighteen years after the first edition (review), original author Anthony Ham returns with new co-authors to give this huge country another sweep. In that time guidebook sales have collapsed, but by all means knock yourself out online trying to collate the broad spread of information amassed here. Providing it’s done well – never an easy job, even with today’s internet resources and let alone in Algeria – this is why a pocket-sized guidebook still works. And after half a century in the business, LP have a new look which has refined the art of laying out a guidebook to be eminently ‘dippable’ while perhaps dumbing down on old-school authoritative content which made LP the leader in this field. This unimpressed poster on Trip Advisor describes the new look as ‘experience-focussed design’ but flick open any spread and you’ll be drawn to something of interest.

My pros and cons below:

- Great price for what you get despite the flaws listed below

- Reader-friendly design

- I don’t know the north, but it looks superficially well covered and interesting

- Need for guided tours plus escort aggro not glossed over

- Locals’ and influencers PoV and contributions a nice touch.

- As before, fails to get the big picture down south

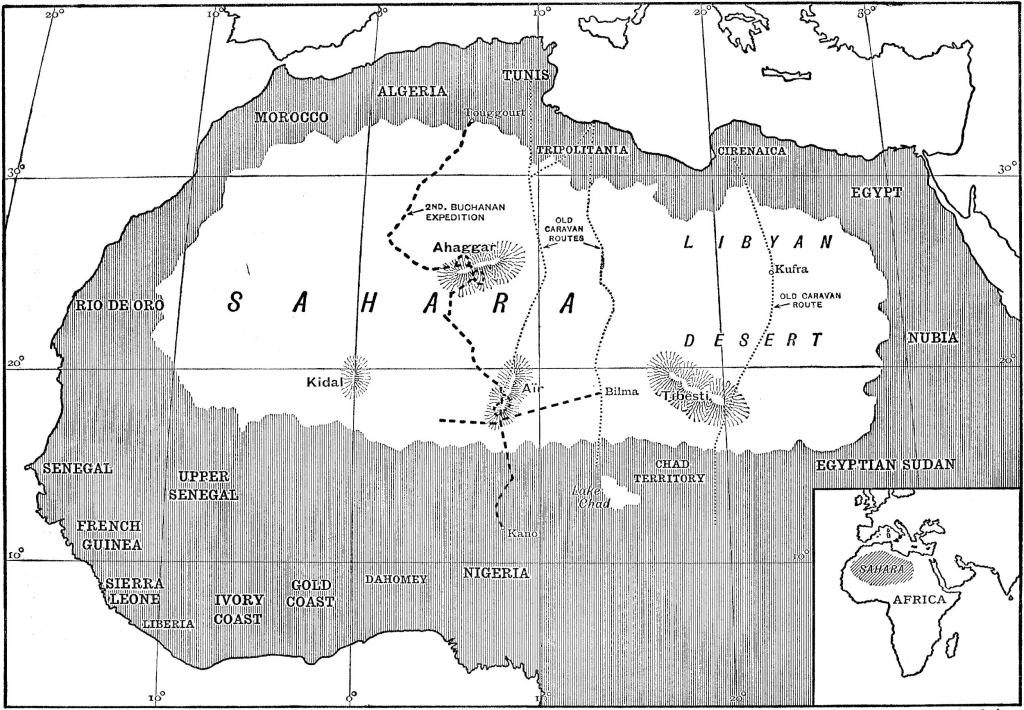

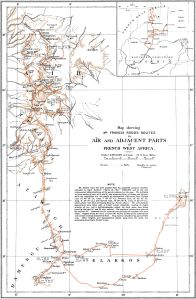

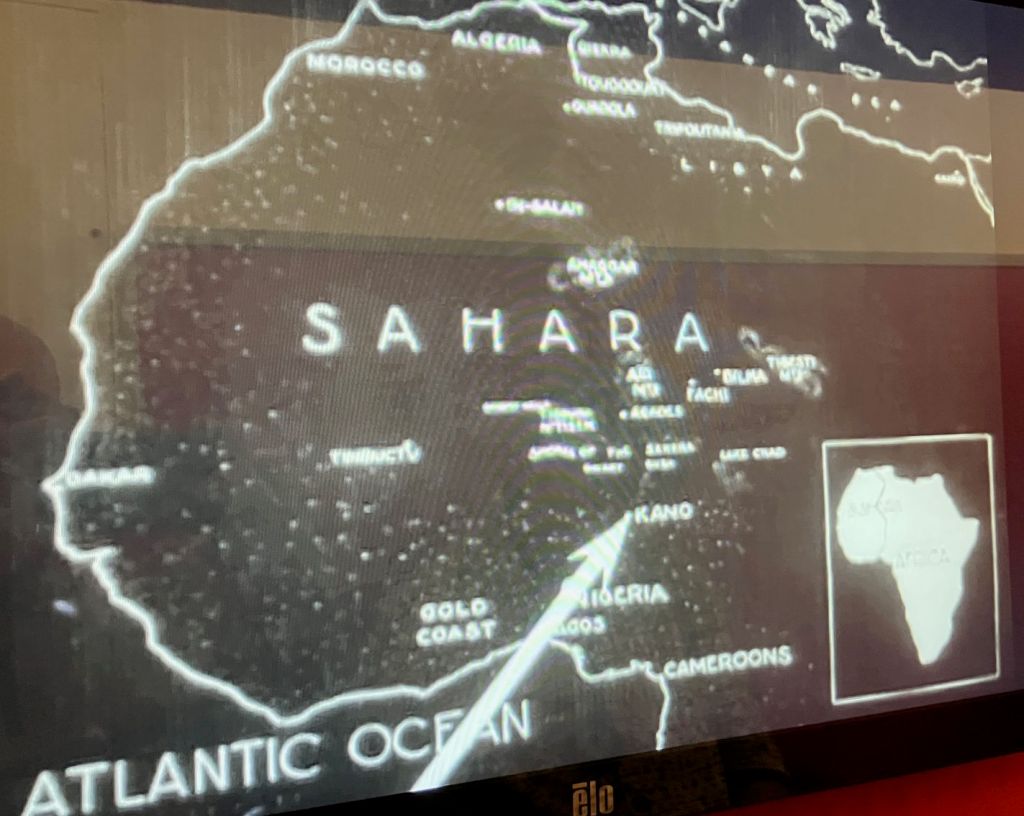

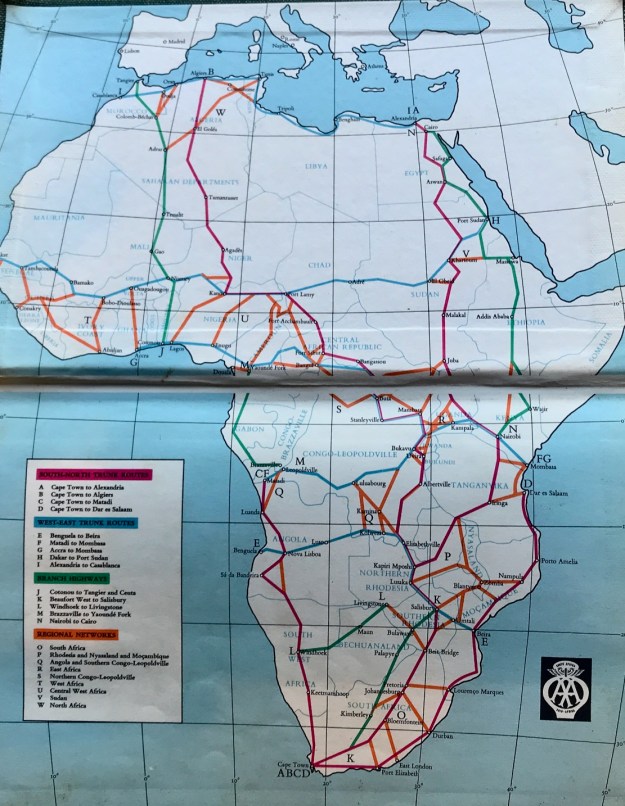

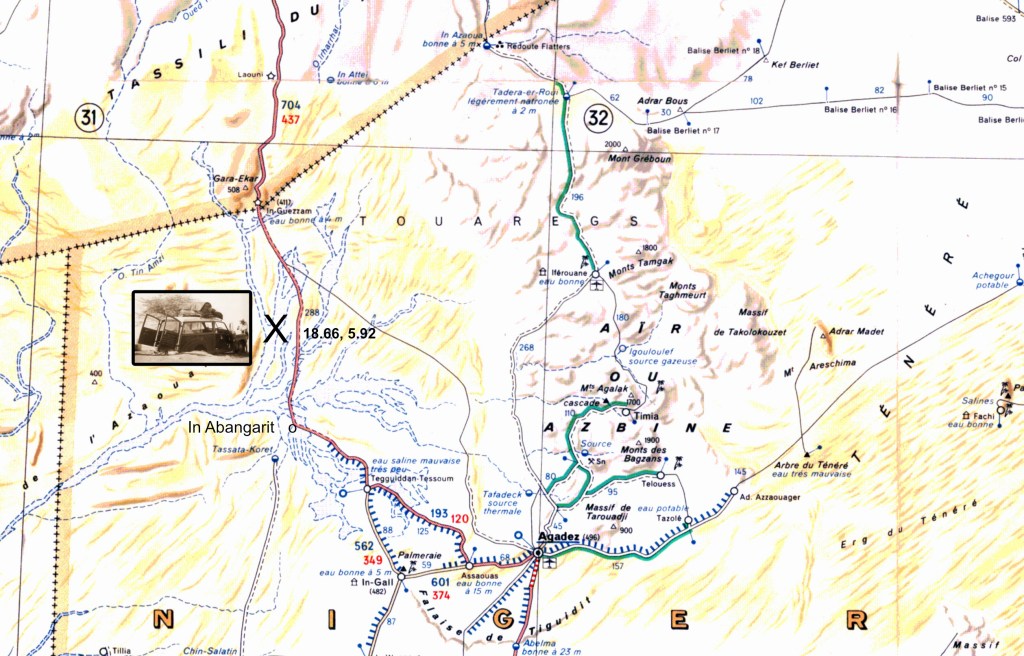

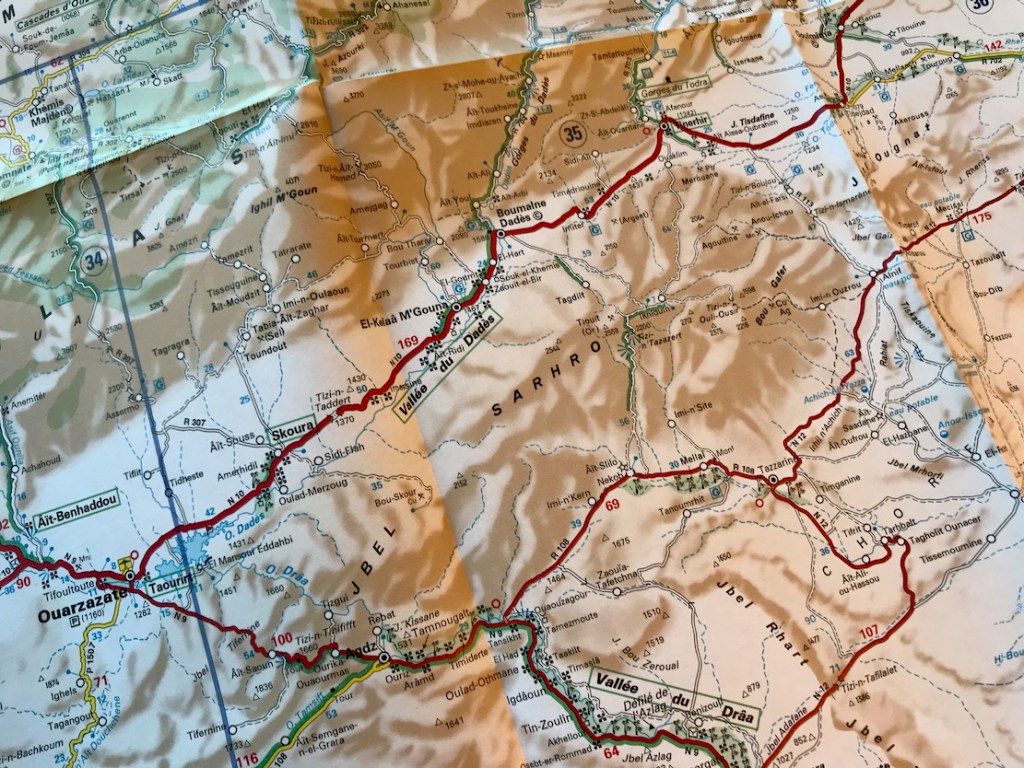

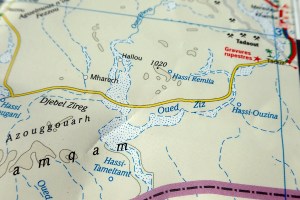

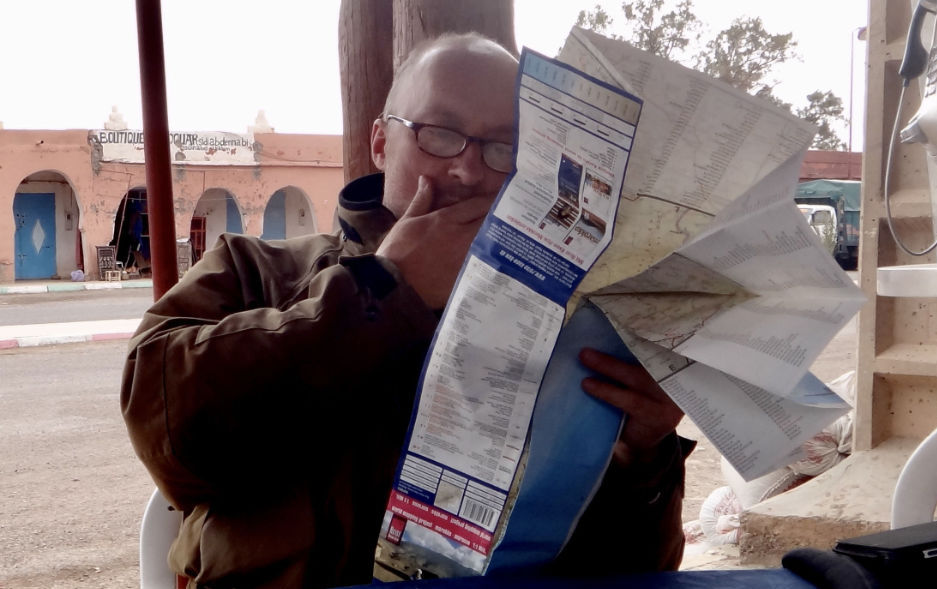

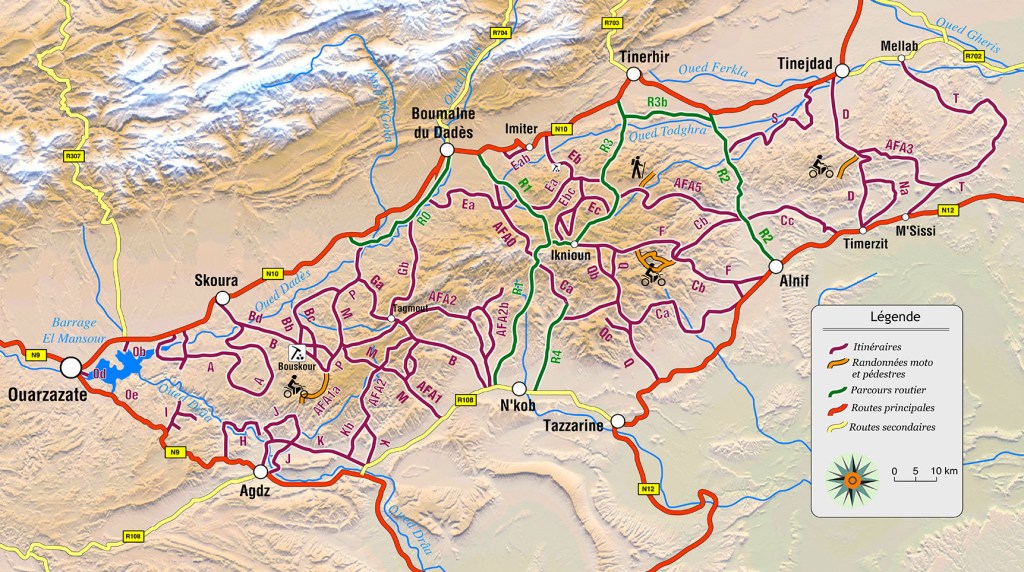

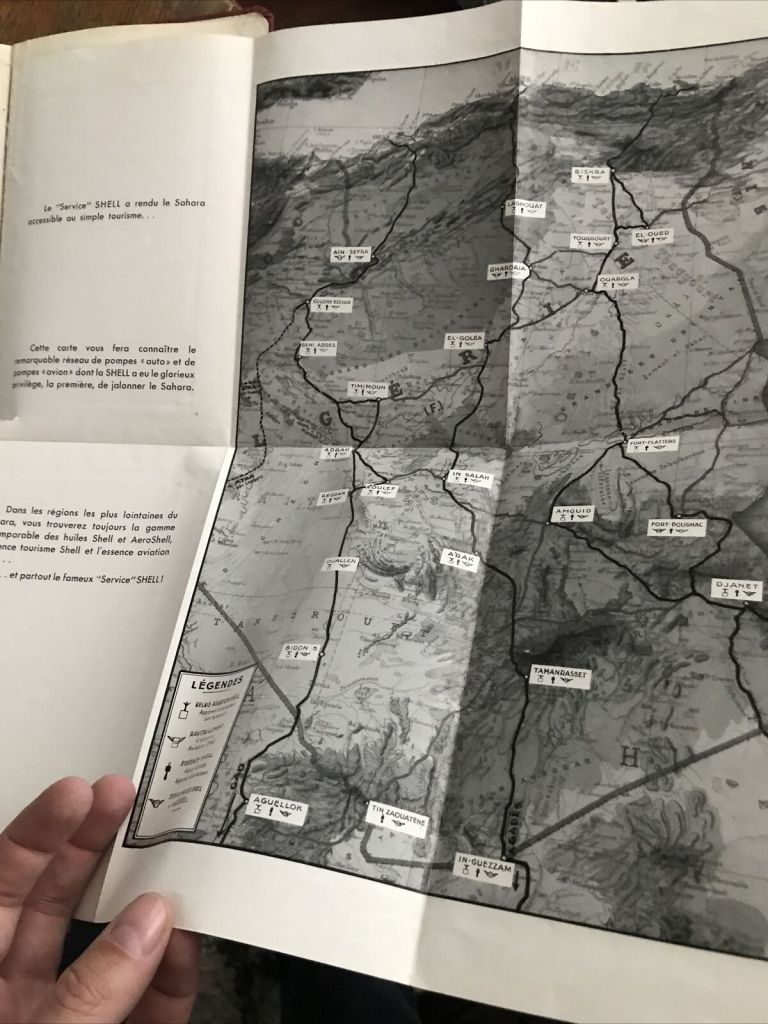

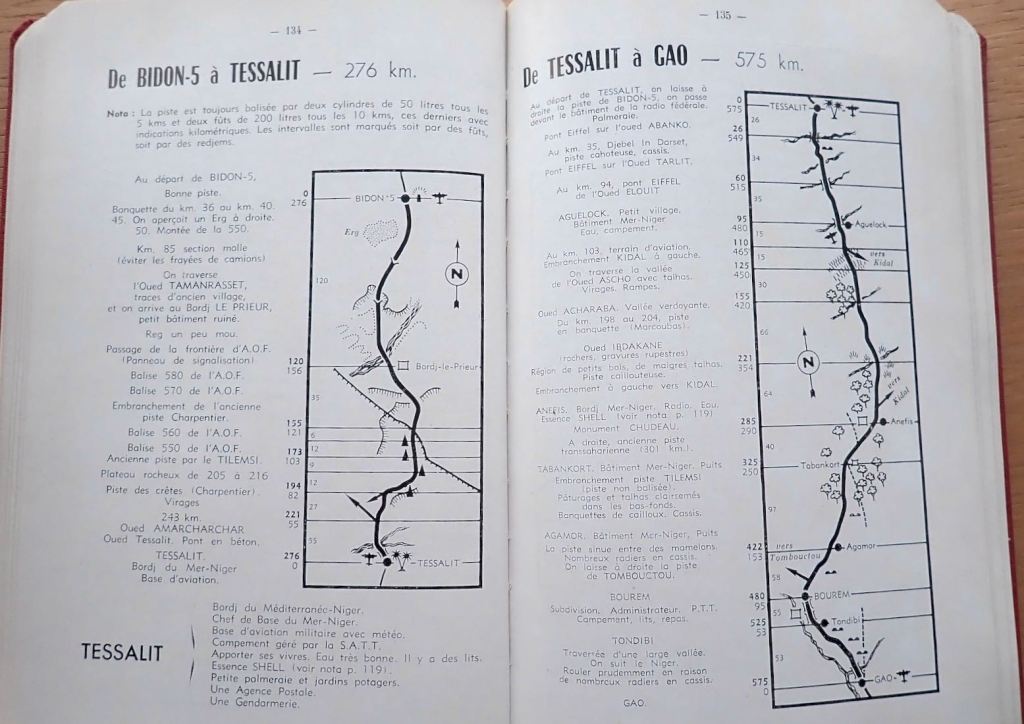

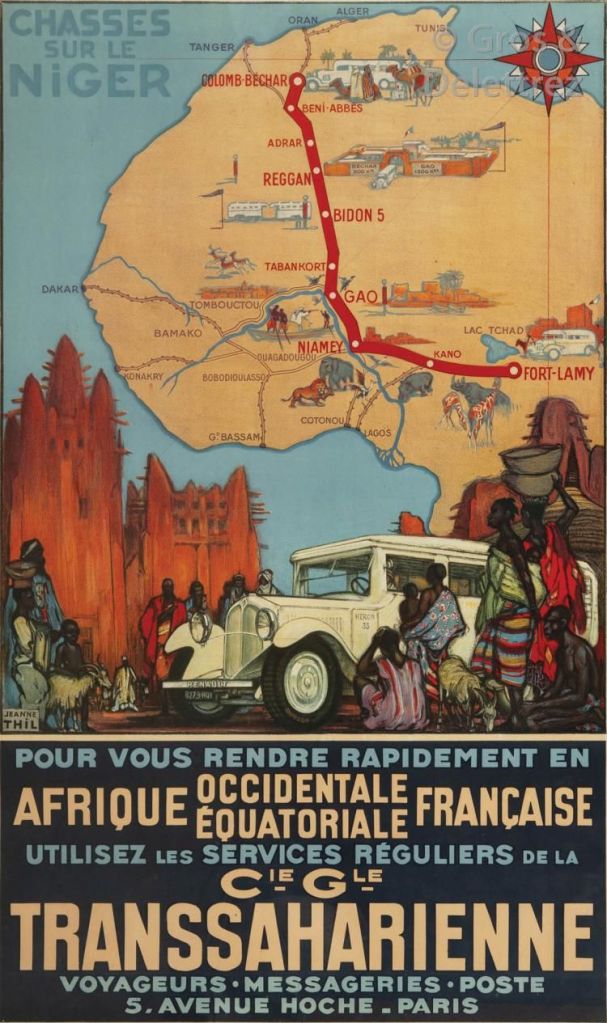

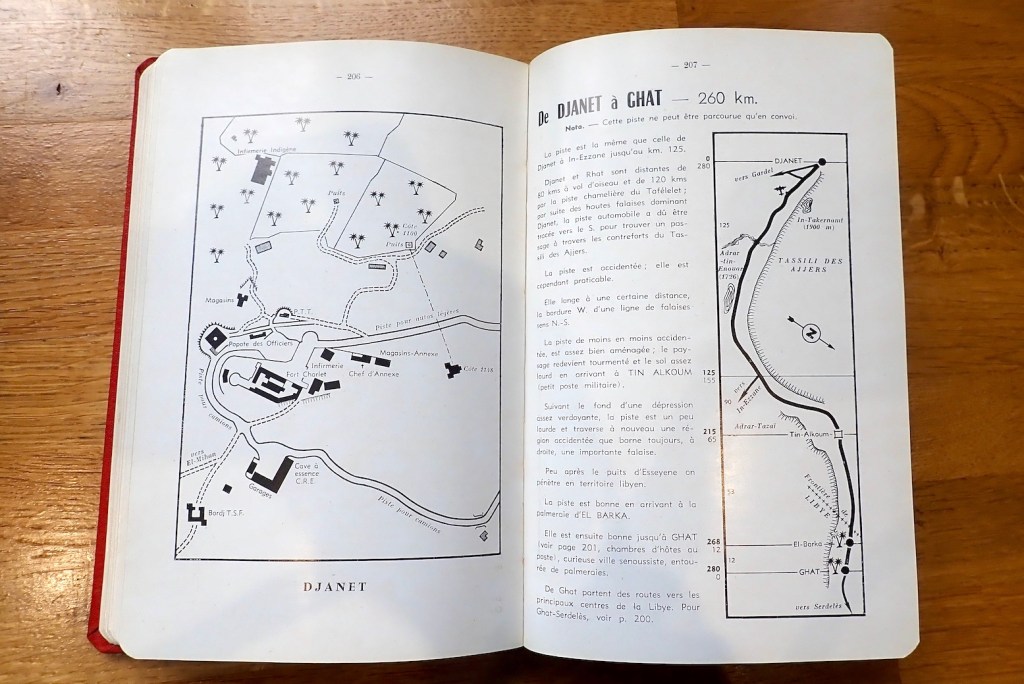

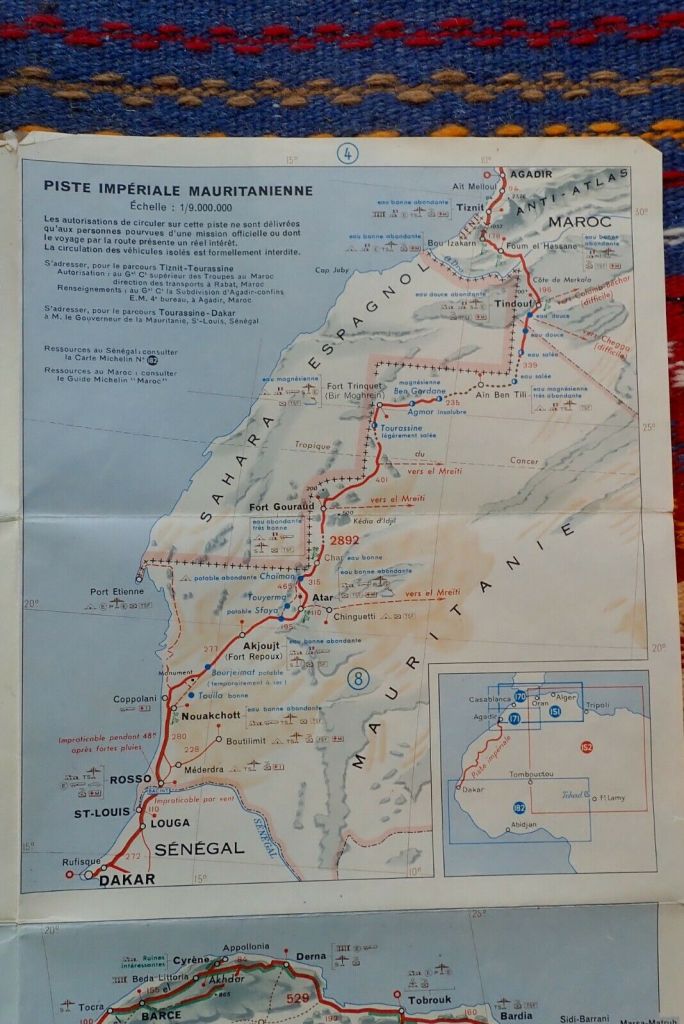

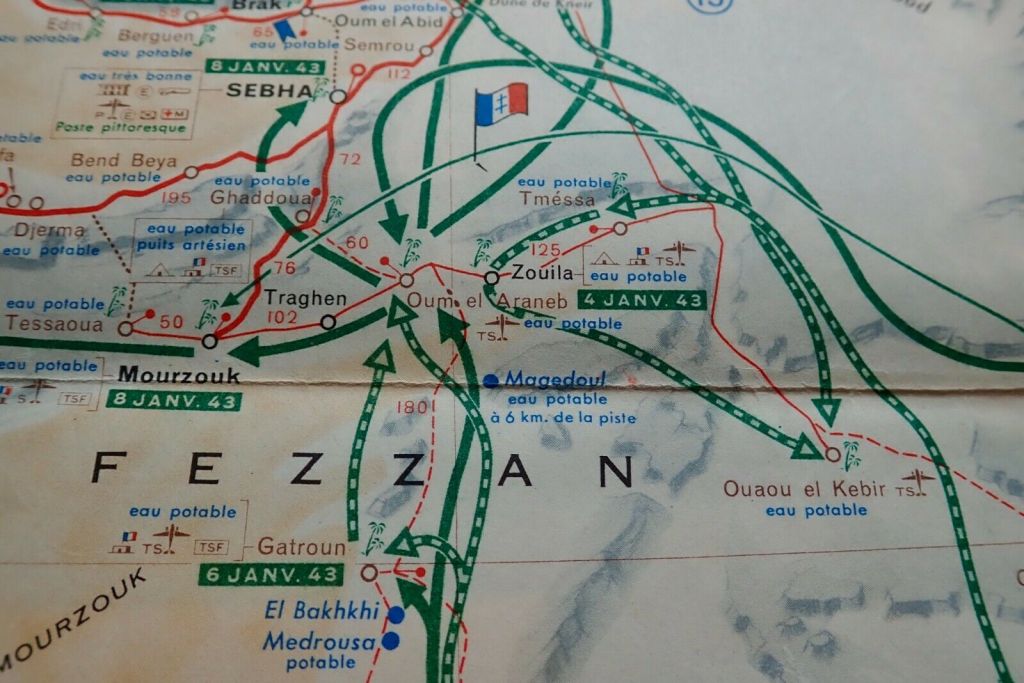

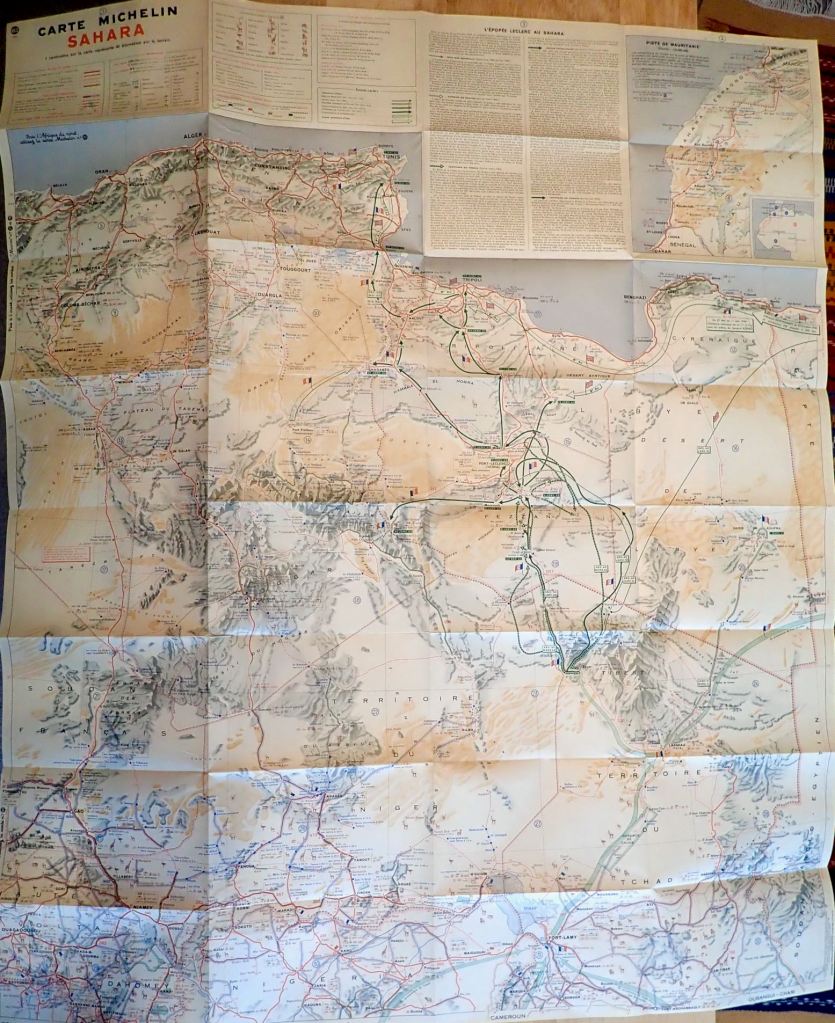

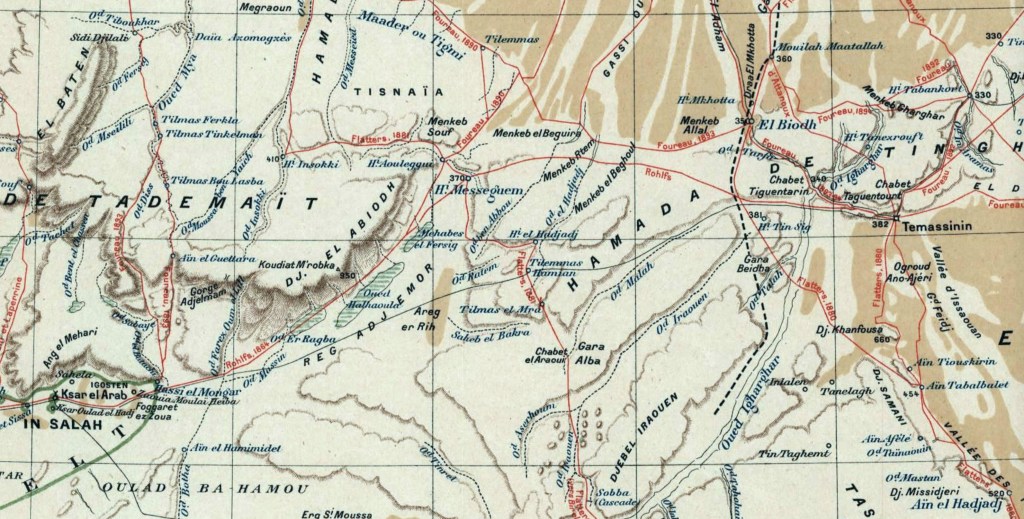

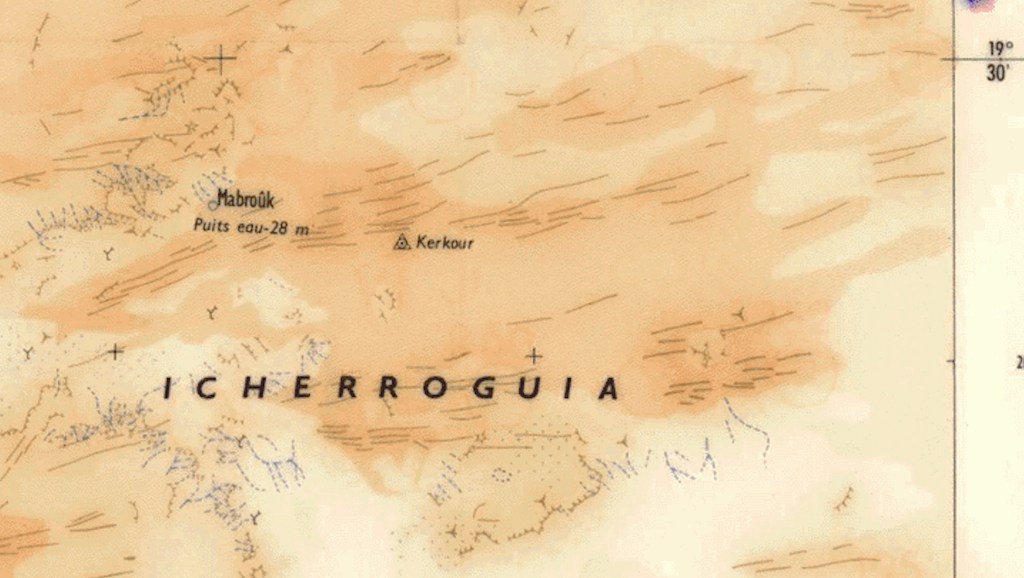

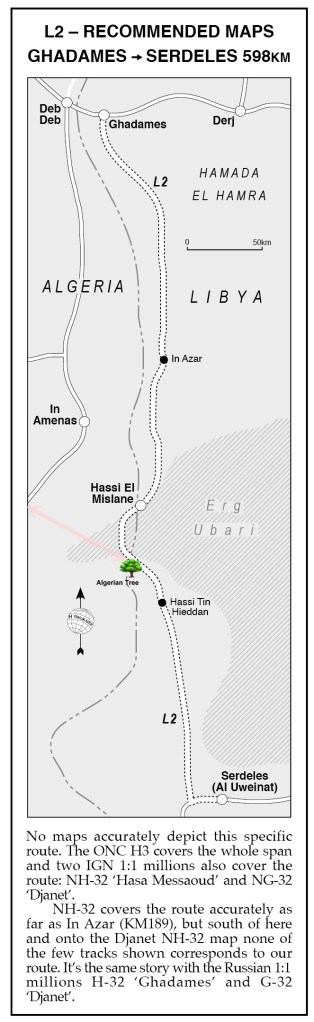

- Maps are plain, many with small errors, don’t distinguish main highways from tracks (some non existent), nor show road numbers or some places referenced in the text

- Couldn’t find a legend for the tiny, inscrutable map icons

- Generic library photos feel disconnected from body text – as if there were two separate editors at work

- Loads of repeated info/boxes (eg: Foucauld) plus a few pointless or obsolete boxes carried over too, like 153 Club

- Bizarrely, nothing at all on camel trekking practicalities, surely the best way to experience the true Sahara

- Why recommend flying between Djanet and Tam when there’s a spectacular desert road?

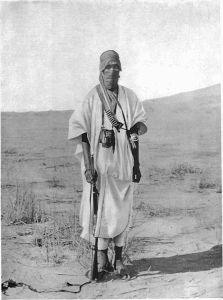

- Despite apparently being in the Immidir for ‘1000s of years’ (p259), you’d think the Tuareg (pictured on the cover) would make a good two-page spread

- Many place names or spellings are unknown or unrelated to long-established mapped precedents

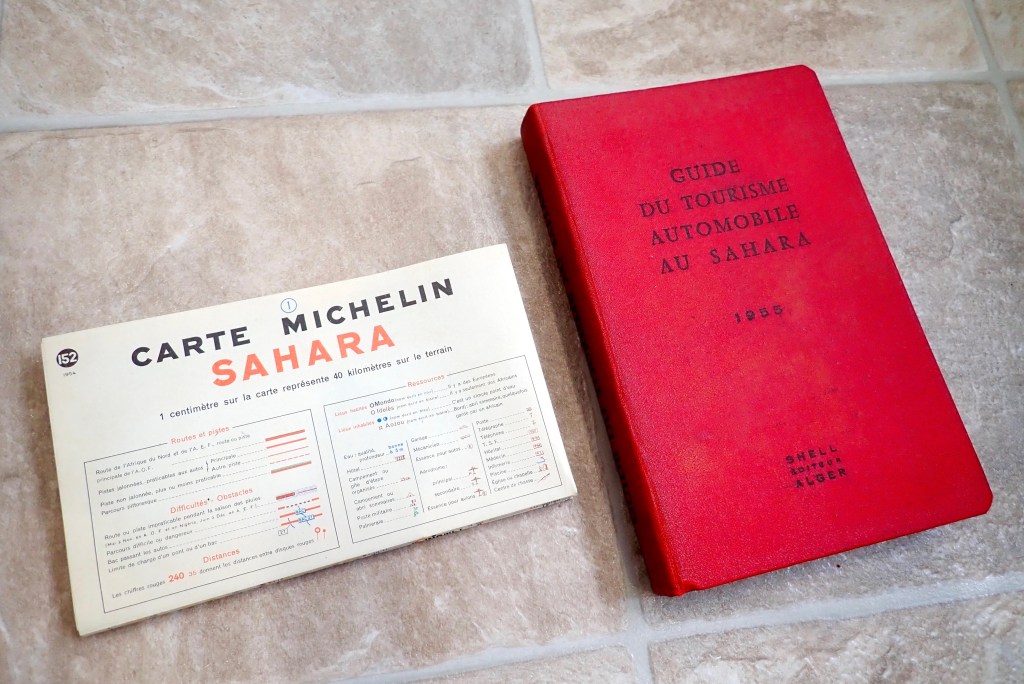

- Grumbles about sourcing ancient paper maps; so why not research/suggest an alternative for a device?

- ‘Bedouin’ tents/tea/etc – in Algeria?

- Detailed maps of ‘Sefar plateau’ and Tadrart would be helpful to ID the many places mentioned

- Insistence on amusingly alliterative headings doesn’t always work and makes what follows all the more fluffy

- Odd absence of other/European sources of background, history, adventure, reading, coffee-table books and so on. Deliberate or just an oversight?

- 1990s civil war and resultant contemporary social issues also overlooked

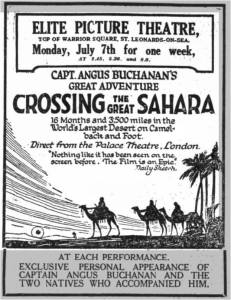

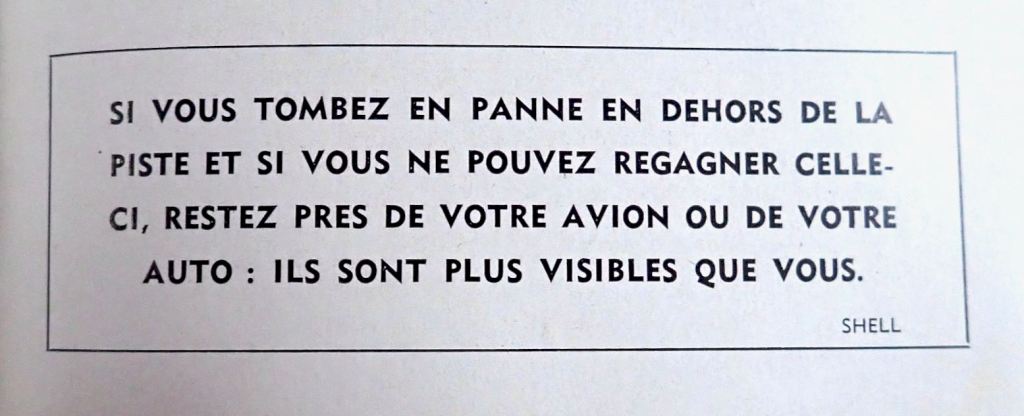

- Confusion about travelling with ‘… Camel or on Foot’. Despite what’s implied for Sefar (p300), ‘Camp[ing] out under Saharan skies‘ (to quote the back cover) is contingent on pack animals or a jeep. You won’t survive long in the desert without either

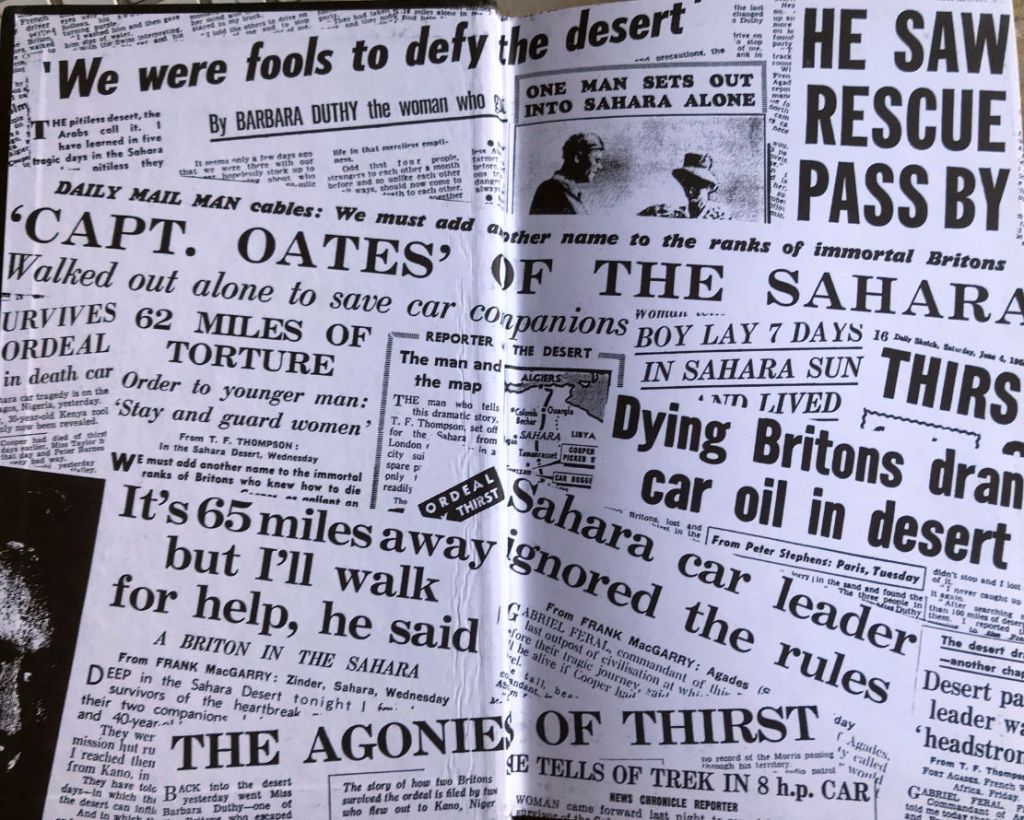

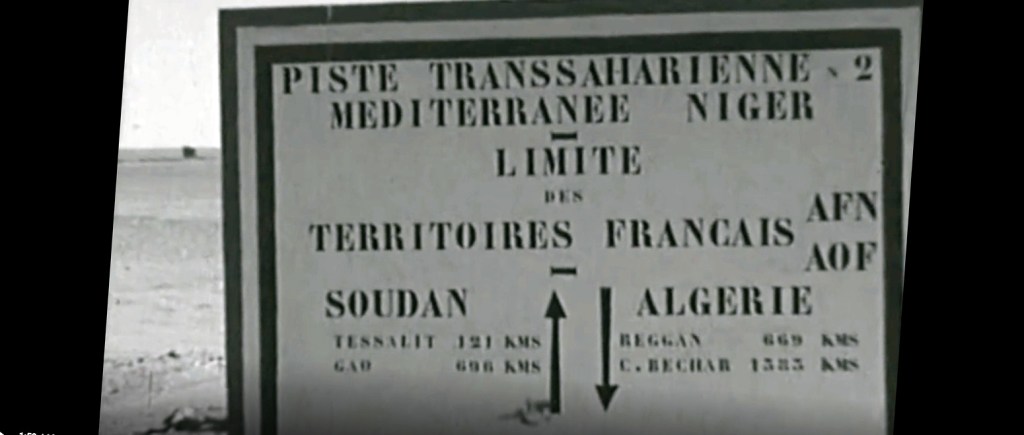

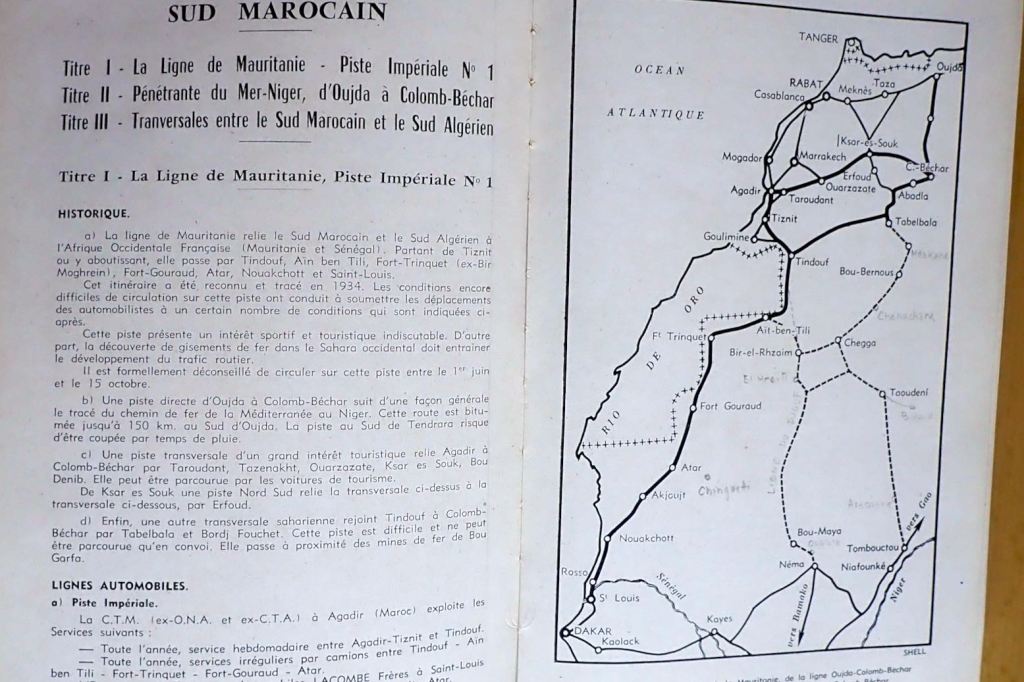

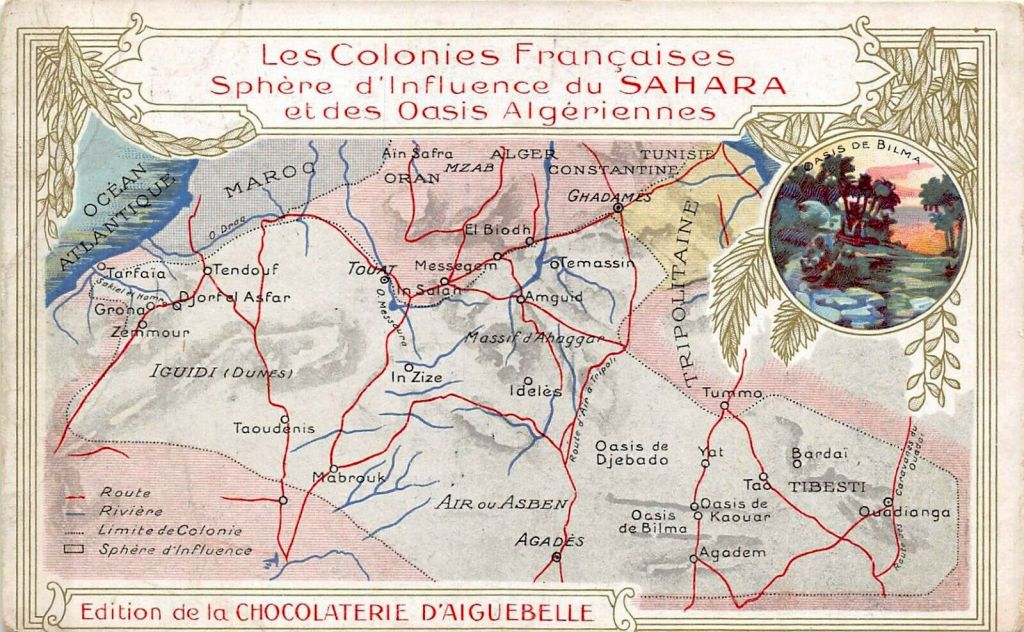

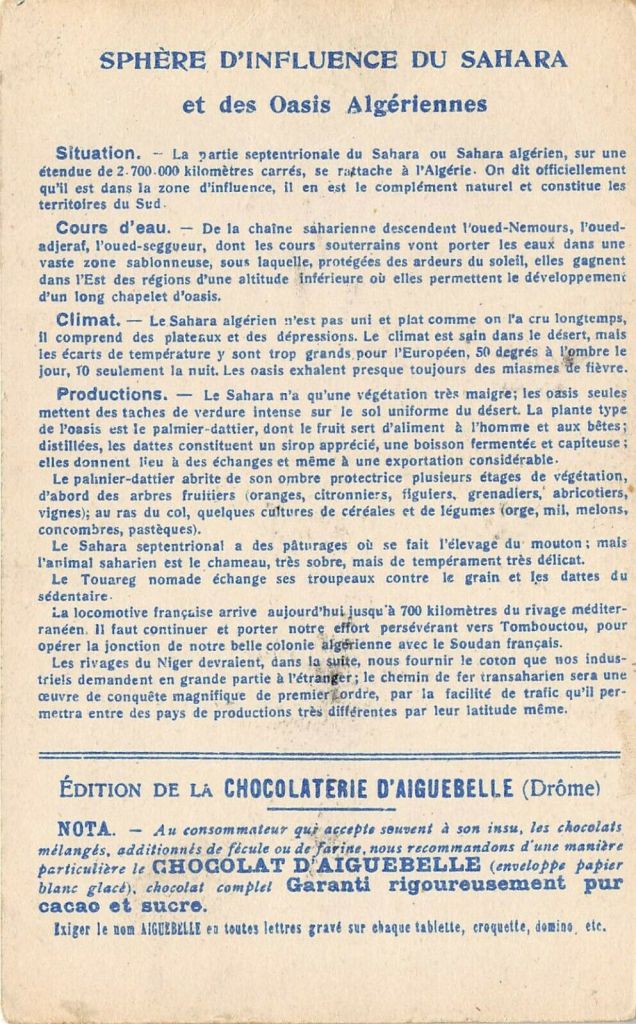

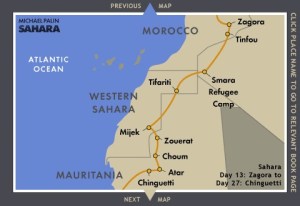

To people like me who’ve visited le Grand Sud dozens of times over several decades, Algeria is the Sahara and the Sahara is Algeria. Scenically, culturally and historically it’s all here in one huge, relatively safe and welcoming country. But this being an LP, the populated north (not so safe at the time of the first edition, iirc) gets the full treatment: coastal cities, Roman ruins, Kabylia and the Aures mountains and beaches. We must have beaches. The far west (Tindouf and the the way to Mauritania is not covered nor explained.

Despite global tourism’s onward spread, your average Planeteer may need reminding that Algeria resembles Iran, Myanmar or North Korea in terms of visa applications and travel restrictions. Since the 2003 mass kidnappings, you need a local travel agency invite with an approved itinerary followed by chaperoning in the deep south. On a fly-in tour or in a big group, that’s not a problem and can be fun. For travellers used to independence, especially in an enticing expanse like the Sahara, it soon gets costly and frustrating, especially if lumbered with a crap tour agency crew. Dodging the agency escort rule is possible in the north (and, for a couple of years recently, in the south too), but down south there’s a good chance you’ll also get roped into pointless gendarmerie (not ‘police’) highway escorts (including protracted changeover waits), even when travelling with an approved agency. This is addressed openly and repeated often, and is what holds back Algeria’s overseas tourism potential.

What They Say

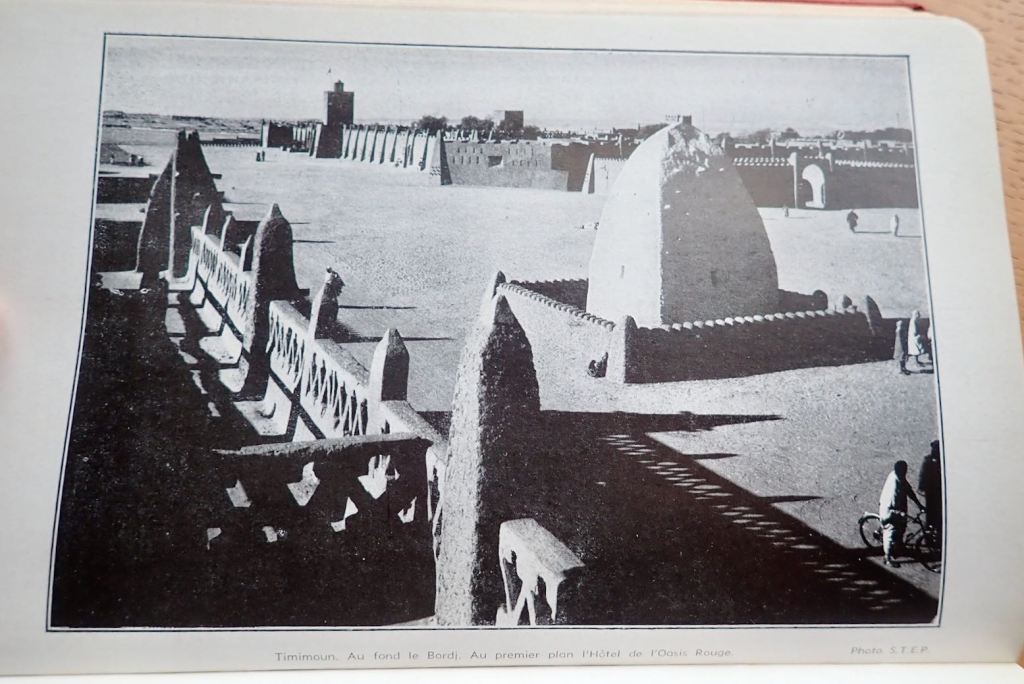

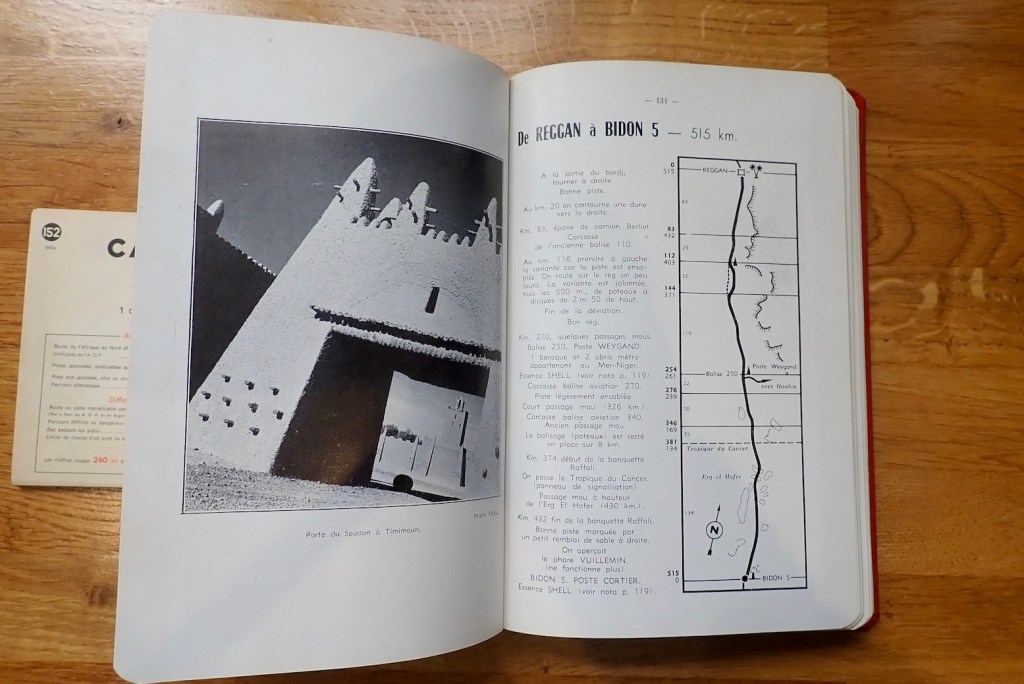

Discover Algeria’s most popular experiences and best kept secrets from sandboarding or quad biking in the spectacular desert oasis of Timimoun; to exploring Tlemcen, an architectural jewel of medieval mosques and palaces; and gazing in awe at the 15,000 prehistoric petroglyphs [sic] at Tassili N’Ajjer National Park.

Build a trip to remember with Lonely Planet’s Algeria travel guide: Covers: Algiers, Tipaza, Constantine, Djemila, Annaba, Timgad, Tlemcen, Oran, M’Zab Valley, Timimoun, Beni Abbès, El-Oued, Tassili N’Ajjer National Park, Assekrem, Tassili du Hoggar [not covered].

Review

The guidebook is divided into into four sections. Only bold sections below were read end to end; the rest was scanned. Added up, the two Sahara chapters cover about 40% of the Guide section.

PLAN YOUR TRIP – 50pp (Highlights)

THE GUIDE 230pp

– Algiers – 28pp

– Northeast – 42pp Algeria (Roman ruins)

– Oran – 20pp

– Northwest Algeria – 18pp

– Central Algeria and the Grand Ergs – 44pp (Northern Sahara)

– Tamanrasset, Djanet and the Sahara – 48pp (Deep south and southwest)

TOOLKIT – 14pp (Travel practicalities)

STORYBOOK – 14pp (Cultural background)

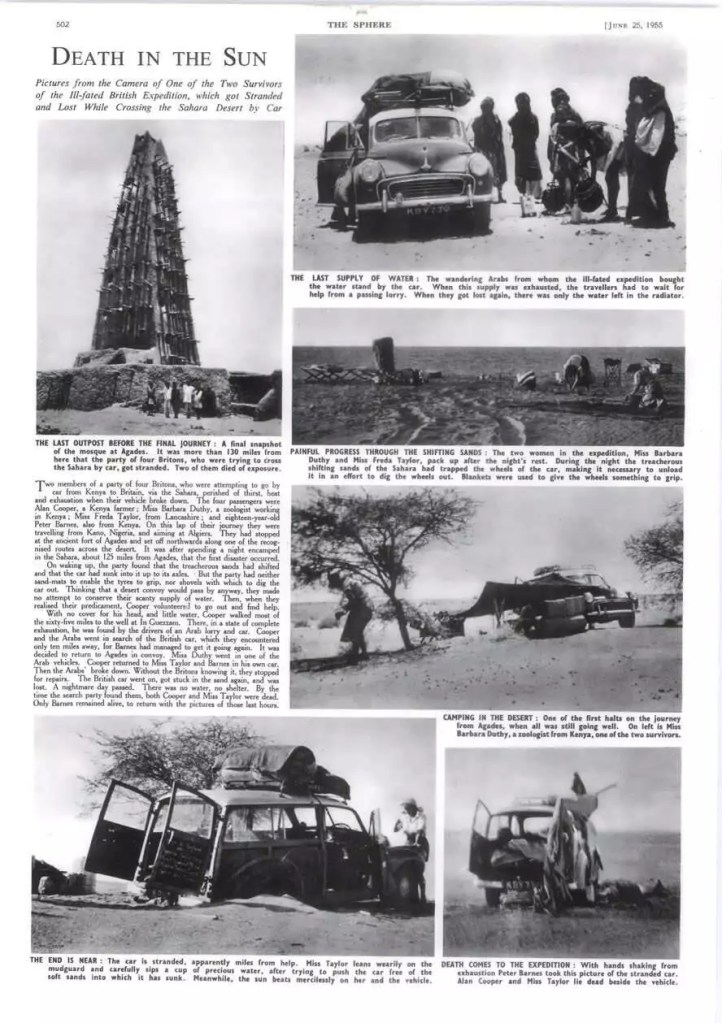

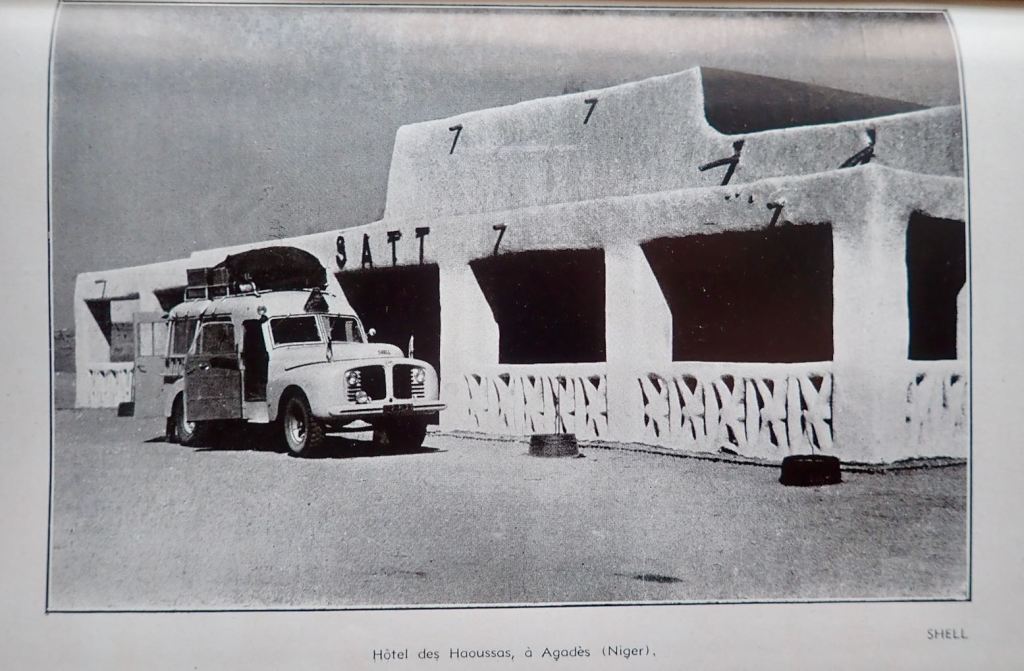

Opening the book, a striking Shutterstock image of granite monoliths (below) jumps off the Contents page and is reused here. Captioned ‘Tassili N’Ajjer NP’, it didn’t resemble the distinctive sandstone ‘tassili’ ramparts and canyons I knew. Searching online drew no answers, except for this similar image by Tom Sheppard, which I’m fairly sure is in the distinctive Tesnou region west of the TSH and miles from the Tassili NP.

This isn’t the first guidebook I’ve reviewed recently that’s entirely illustrated with library photos, with authors now template-filling content providers. But as listed above, it’s common to read an evocative description and think ‘I wonder where that is or what it looks like’. The text and imagery, even the maps, often feel disconnected.

Upfront, Plan your Trip lays out highlights of the Guide’s five regions followed by suggested Itineraries. The northern ones look good, but what do I know? Down south ‘Into the Heart of the Atakor’ oddly suggests going from Tam up to Assekrem, then coming back 80km and back up the western approach as far as isolated Ilmane peak (left) which is just 22km west of Assekrem. It’s hard to think why this wasn’t a straightforward 200-km overnight loop via both locales, except later on the missing link is described as a ‘dangerous short-cut’ or ‘perilous clifftop traverse’. Really?

There follow spreads including when to go, Ramadan, dress and manners, visiting the desert and choosing an agency (I tried a few; only two replied; usual story), the food scene, getting a visa (pre-approved VoA a staggering €365 for 30 days, vs £85 at a consulate) and the Outdoors.

After the Guide Toolkit practicalities cover arriving, getting around, money (black market recommended, but why US dollars?), lodgings, health and safety (‘avoid Algeria’s border with ‘Western Sahara’; except there isn’t one), women travellers, language and so on.

The book ends with Storybook articles which tackle a sketchy History in 15 Places rather than chronologically, a skimpy ‘Meet the Algerians’, Algiers artists, prehistoric rock art and the Algiers Casbah (left) – site of bitter independence battles in the early 1960s and now an ‘old town’ tourist attraction. Storybook would have been a perfect place to expand on the Tuareg, their enduring mystique, origins, traditions, clans, rebellions, persecution and all the rest. Libraries and the web are awash with material.

Backing up to the two Saharan sections of the Guide, the Ergs and Oases looks like a pretty good account from El Oued to Taghit via Ghardaia and Timimoun. In El Oued the ‘Top Experience’ spread covering camping and quad biking in the dunes is rather reluctantly rendered, and there’s confusion about the location of the Tademait as well as Ghardaia being ‘south’ of Ouargla (it’s WNW). On p212 there’s another typical example of repetition: a column on the left talks of Convoys (escorts) while the body text alongside has a heading ‘Police escort’ – the same thing. They mean the paramilitary gendarmerie (a big difference), but where is an editor? I also get the feeling that too many of author’s subjective encounters are passed off as typical reader experiences because of a lack of actual background knowledge or context. In the meantime, it looks like I’ve long missed the boat to visit once lovely Taghit; now reduced to a dune-bashing desert resort, like Erg Chebbi, just 190km to the west.

Moving on to ‘Tam, Djanet & the Sahara’, as with the previous edition it’s either one or the other with no connection between the two towns or ‘hubs’, other than proposing a flight, which if in daylight ought to be amazing. As mentioned above, the suggested convoluted itinerary into the Atakor (Assekrem) seems odd, and is there really a place called ‘Guelta’ near Terhenanet? Maybe authors no longer get to check finished proofs. And you’d think the beautiful Tazrouk loop out of Tam, let alone the N55 to Djanet would’ve been a great desert itinerary too. Meanwhile, the distinctive Tefedest and Arak Gorge (marked earlier on the ‘Action Areas’ map as an ‘extreme adventure’ locale) share a sentence, then don’t get another word. In Salah turns into a masterful exercise in padding – another sunset dune venue (yawn), while dodging actual POIs, scant though they are. It may only be listed to pitch as a hub to visit the nearby Immidir (below), by which time the author is definitely winging it in full flow. One person can’t be expected to visit every amazing corner of the desert, so why not track down contributors to fill the gaps?

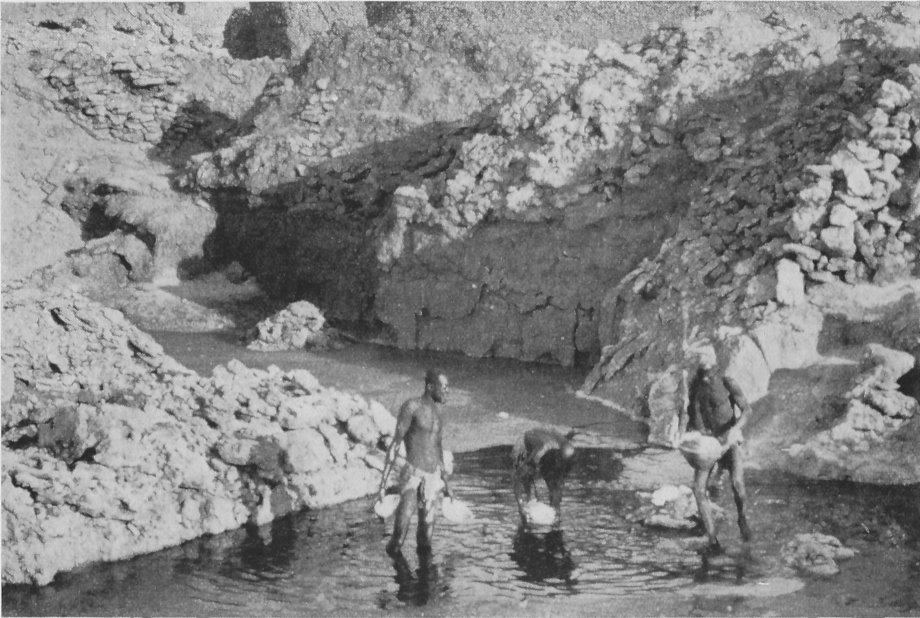

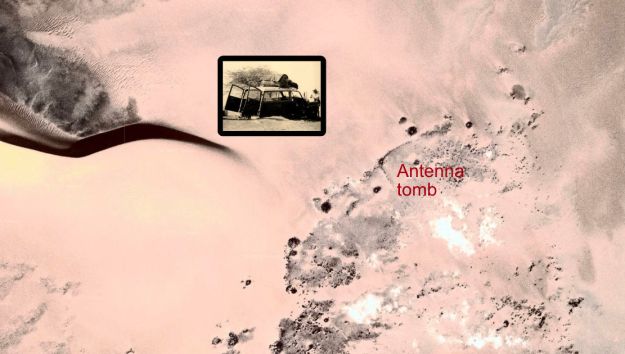

In Djanet the famous Tassili plateau walk is listed and illustrated with stock images of the best known places, but doesn’t seem like it was actually done. The now over popular Tadrart (Oued In Djerane canyon, not ‘plateau’) may have been visited – maps for here and the plateau rock art walks would help readers visualise these regions. After that it seems the author was taken on a random drive to Tasset on the Fanoun (no mention of amazing Afara round the corner) followed continuation to dead-end Ifni, of all places. Around here I realised there was not a single image nor mention of the massive megalithic pre-Islamic tombs (below) which you drive right past in these areas.

In the face of hotel booking websites, the formerly tedious job of researching the best lodgings for the reader has been revised down to a quick handful of ‘Places we Love to Stay’, even in the north where you might wander unchaperoned and value curated suggestions. There are only eight in the entire South – three a-piece in Djanet and Tam where the old town centre Hotel Tinhinan is described as a right dump. Thanks for the tip: in five seconds great alternatives where I would love to stay spring up on Google.

In the end the desert south reads too much like a quick update to the first edition which itself was skimpy. A night in In Salah, a couple in Tam ticking off Assekrem, with a bit more time rightly spent in the Djanet area. No serious attempt has been made to get under this amazing region’s skin. That’s a shame but may be the reality of today’s budget-constrained guidebook research and production. To be fair that’s also reflected in the book’s price where you’ll still find 15 quids’ worth (or less on amazon) of ideas and inspiration between the covers.