Part of an Sahara A to Z series

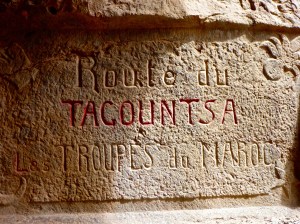

‘Free Solo’ is a documentary covering Alex Honnold’s mind-boggling, rope-free ascent of El Capitan in Yosemite, California in 2017 (left). If you’ve seen it you may recall that, among other places, Honnold practised on a hidden cirque of cliffs surrounding the scattered hamlet of Taghia, buried about as deep in Morocco’s High Atlas as you can get. A couple of rudimentary gites cater for visitors but, even among Moroccan know-alls, unless you’re a rock climber you’ll have never heard of Taghia. The only way in is a four-mile mule trek through a canyon from the valley head at the equally obscure outpost of Zuweiat Ahansal, an hour or two’s ride south of Rocher de Mastfrane, better known as the ’Cathedral’ (below).

I rocked up at Zuweiat one lunchtime just as a group of young American climbers were spilling out of a taxi, and continued over the bridge to the edge of the old town. I pulled over for a snack and, unsure of the way and not wanting to blunder on, asked a passing local whether it was possible to ride a bike to Taghia and if yes, which way?

‘Oh no’ said the old man. ‘You can only get there on foot.’

I finished my snack and thought it over. Back by the bridge, I sought a second opinion from some more worldly looking dudes hanging out outside the post office. They were eyeing up the new, North Face-clad arrivals and one spoke good English.

‘Yes, I saw you pass and was going to say, you can’t ride your moto to Taghia.’

It turned out he’d worked on the Honnold doc as well as other National Geographic features (below) and, reading his manner with my finely tuned bullshit detector (which they now hand out free at the border), it didn’t sound like the usual bragging. After that, he switched seamlessly into sales mode, offering lodgings and guides.

‘Maybe next time’, I said. I genuinely did hope to visit the mysterious valley, but the weather forecast was a bit shaky for the next couple of days. I wanted to get out of the mountains, not stuck in them.

A year or two earlier a bike-riding climber who’d visited Taghia suggested to me that a small bike (like my Himalayan) could probably reach the cirque following the riverside mule path.

While that may be true, I figured just because I could, did I have to – or even, should I? The local guide may merely have been protecting his mule-trekking services, but I like the idea of leaving some of the world’s wild corners unspoiled by the putter of mechanized transport. As I was about to be reminded, there’s plenty to see in Morocco on a bike or in a 4×4, but there are many places in the world which are best reached by less intrusive human-powered transportation. That’s what makes them special.

2024 and I heard they’d finished the track into Taghia. James and I were in the area recce-ing route for the M4 book. A few months later I wrote this in Adventure Rider magazine.

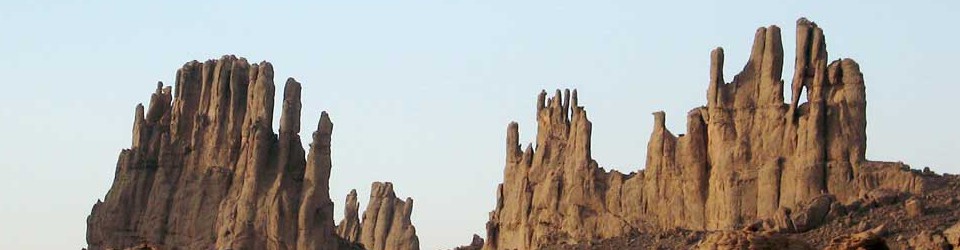

Add a few wraiths of mist plus some digitally enhanced pterodactyls, and the narrow chasm which leads into the Taghia gorge could pass for a scene from Game of Thrones. Burrowed deep in Morocco’s High Atlas, the isolated Berber hamlet beyond was only accessible by mule. So I was told in 2018 when I tried to reach Taghia on my Himalayan. Now they’ve carved a motorable track, so we rode down through the defile, crossed and recrossed a stream, and found ourselves in a small cirque or valley head surrounded by sheer, 3000-foot limestone terracotta crags. I’d not seen a place like this in Morocco. Alex Honnold came here to train in seclusion, prior to soloing Yosemite’s El Cap for the Free Solo movie. He did so by free climbing all three of Taghia’s hardest faces – 6000 feet of big wall soloing – in a single day. “It’s pretty freakin’ next level” he observes with characteristic humility in Before Free Solo, Edge of the Unknown’ (on YouTube).

High Atlas village

High Atlas village Another new road from nowhere to nowhere much. I suppose it helps stir up the local gene pool.

Another new road from nowhere to nowhere much. I suppose it helps stir up the local gene pool. One of these days I’m going to watch a youtube doc on how they build mountain roads.

One of these days I’m going to watch a youtube doc on how they build mountain roads.

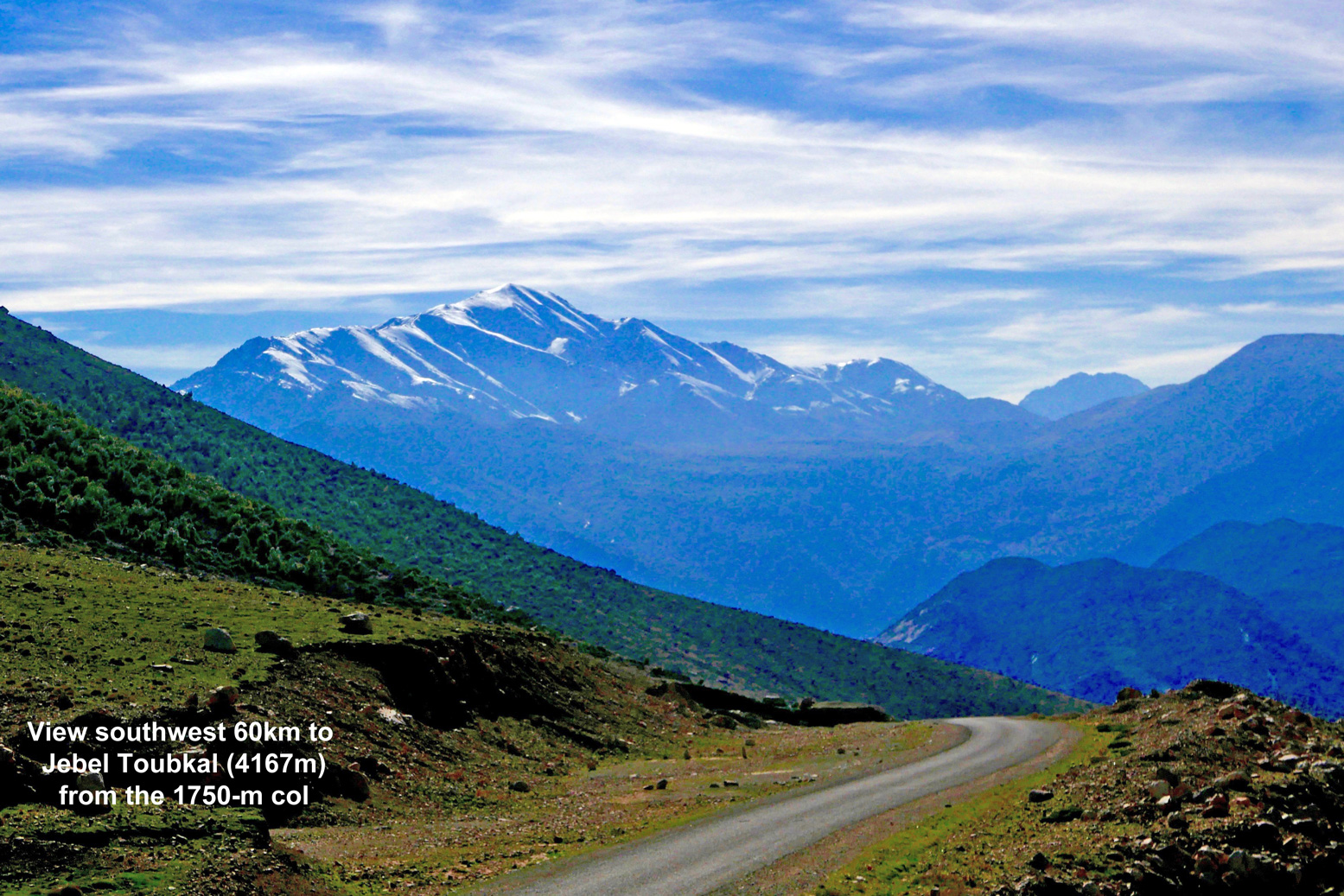

Above the clouds at 2500m or about 8300′ in old money.

Above the clouds at 2500m or about 8300′ in old money. An isolated juniper tree that’s managed to dodge the village wood burners.

An isolated juniper tree that’s managed to dodge the village wood burners. Checking the link route to Map Junction above Ijoukak.

Checking the link route to Map Junction above Ijoukak. 1970s Transit. One of the only vehicle’s I saw today once off the main roads. The other was a Trannie too.

1970s Transit. One of the only vehicle’s I saw today once off the main roads. The other was a Trannie too. Another photogenic village somewhere.

Another photogenic village somewhere.

Sunset at the casbah.

Sunset at the casbah. Always room for a whaffer thin slice of cake.

Always room for a whaffer thin slice of cake.

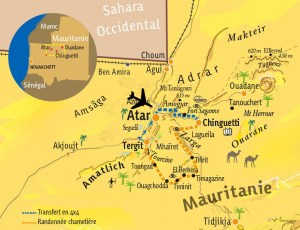

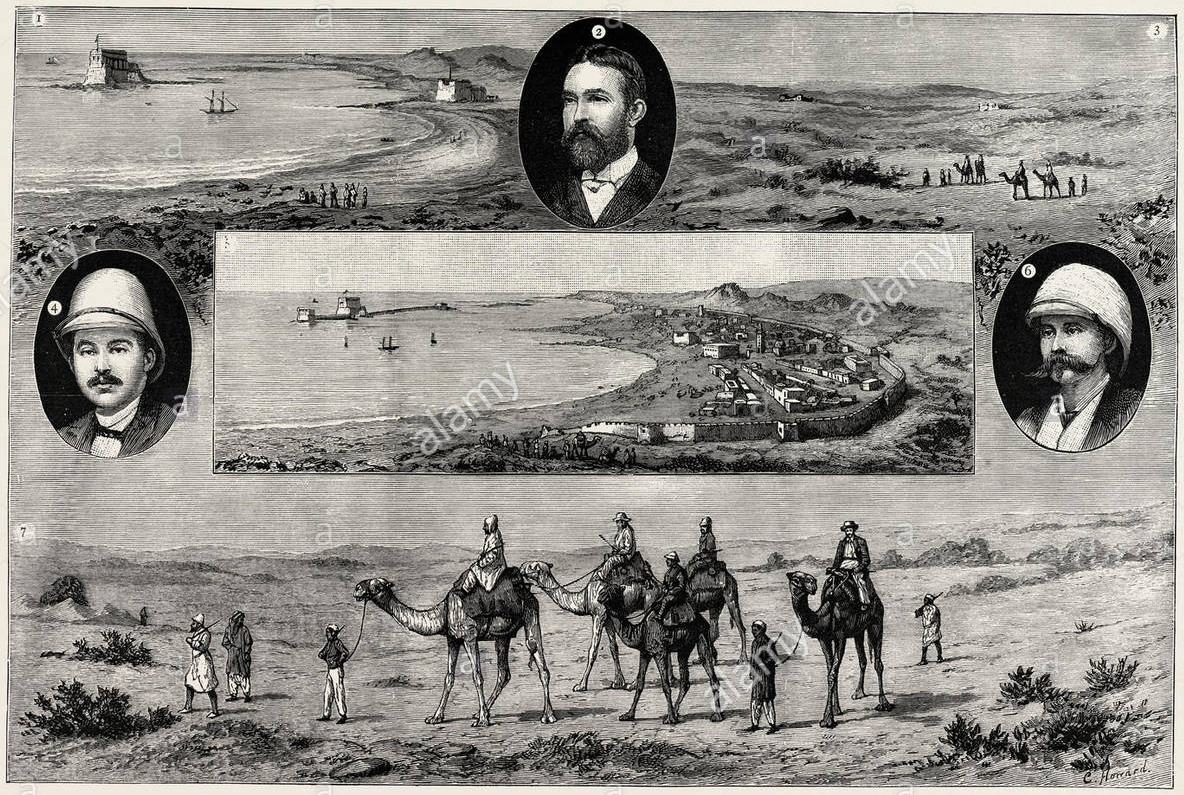

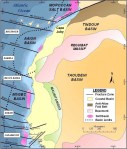

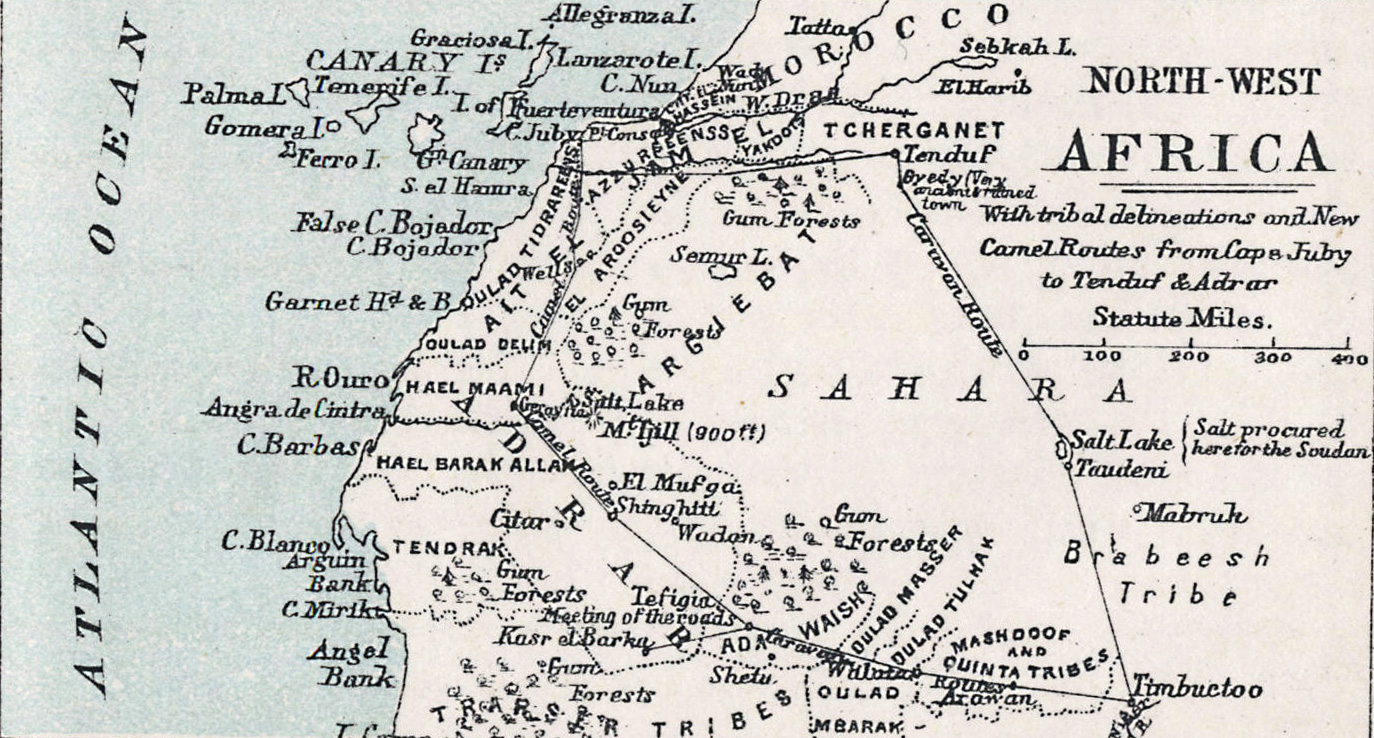

Mackenzie also thought that trade and communications would help liberate the sub-Sahran population from the slave trade. And this wasn’t just a ploy to appeal to investors’ morals or religious beliefs – Mackenzie’s later work in East Africa long after the NWAT Company dissolved suggested he was always a genuine abolitionist.

Mackenzie also thought that trade and communications would help liberate the sub-Sahran population from the slave trade. And this wasn’t just a ploy to appeal to investors’ morals or religious beliefs – Mackenzie’s later work in East Africa long after the NWAT Company dissolved suggested he was always a genuine abolitionist.