Thanks to Danish journalist, Anders Nielsen (a friend of one of the protagonists) for passing on this fascinating article and photos. I tidied up a Google translation and added [my annotations] for added clarity.

Seventy years ago, on finishing a lengthy contract in the late-colonial sub-Saharan Africa, taking on such trans-African adventures was not uncommon. It was assumed a regular car might manage as in many colonies parts of the road network were well maintained and superior to what exists today. But as you’ll read, the near-new Morris Oxford still got quite a beating. The yarn reminds me of Paul Stewart’s Trek (below right; to be reviewed), also in a Morris just a year later, but which ended in tragedy north of Agadez in the Sahara. And of course David Newman’s demented The Forgotten Piste a few years later.

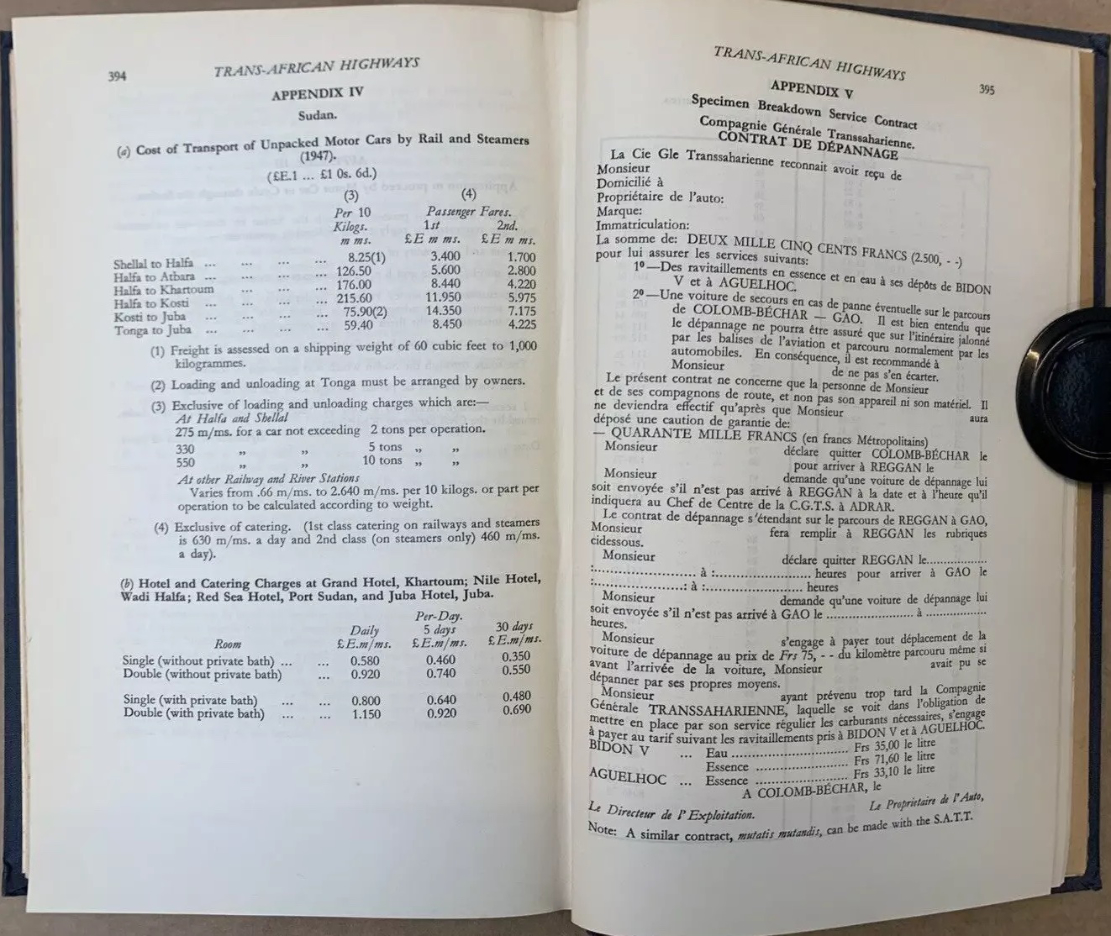

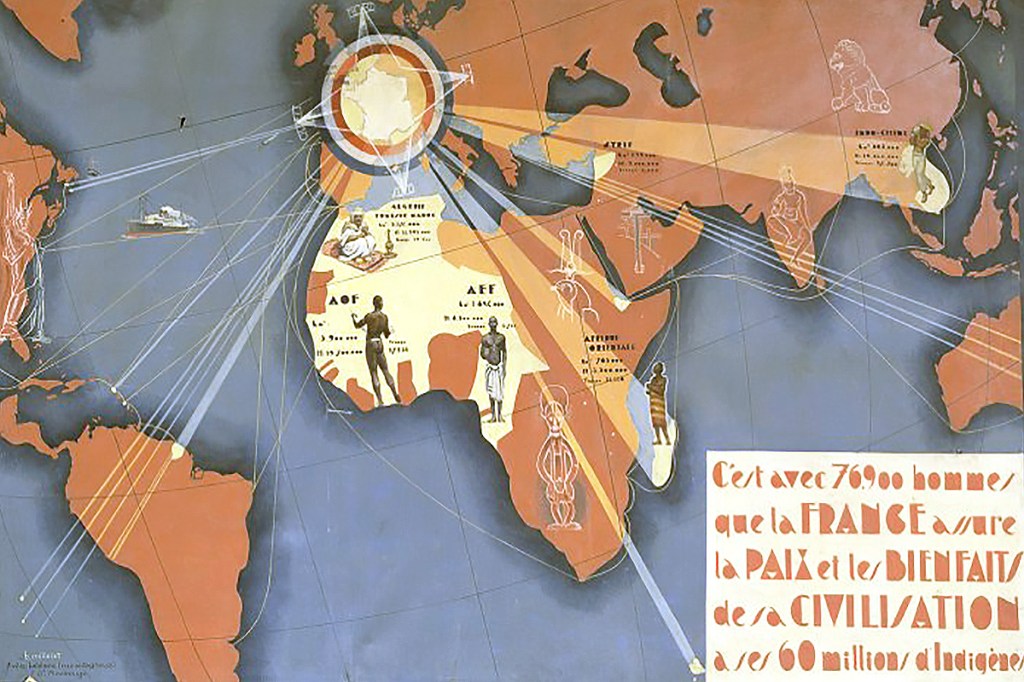

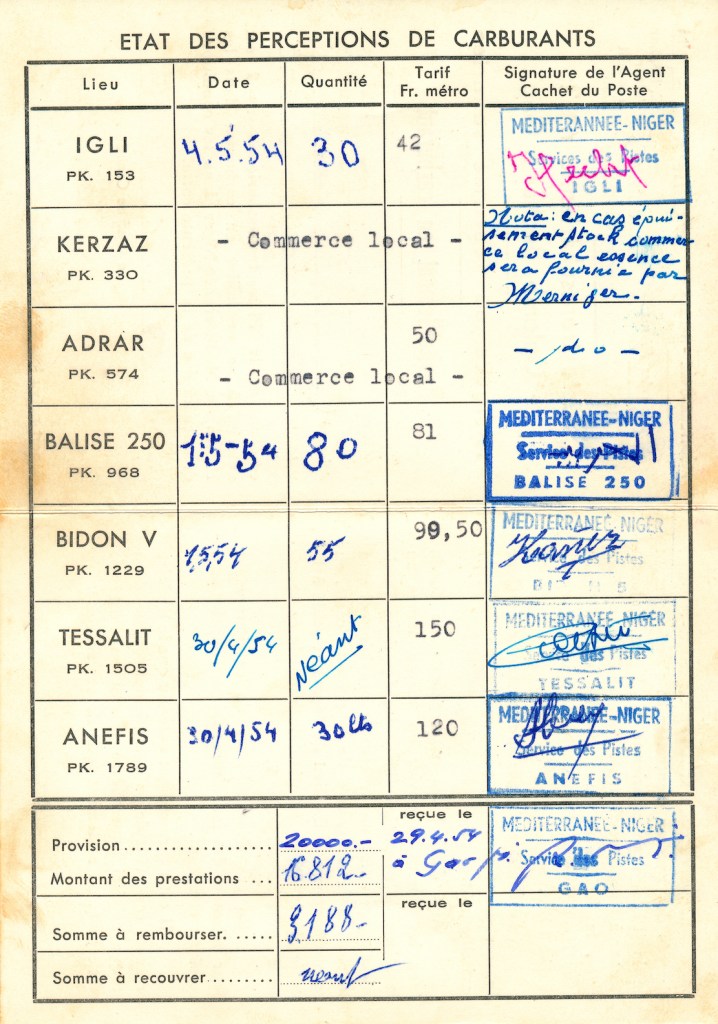

From Kenya to Morocco you’re reminded this era was marked by widespread anti-colonial unrest. It’s also interesting to learn of the huge £1000 bond (2500F + 40,000F) for the Contrat de Depannage (assistance) required to cross the French-controlled Sahara to cover the cost of possible rescues.

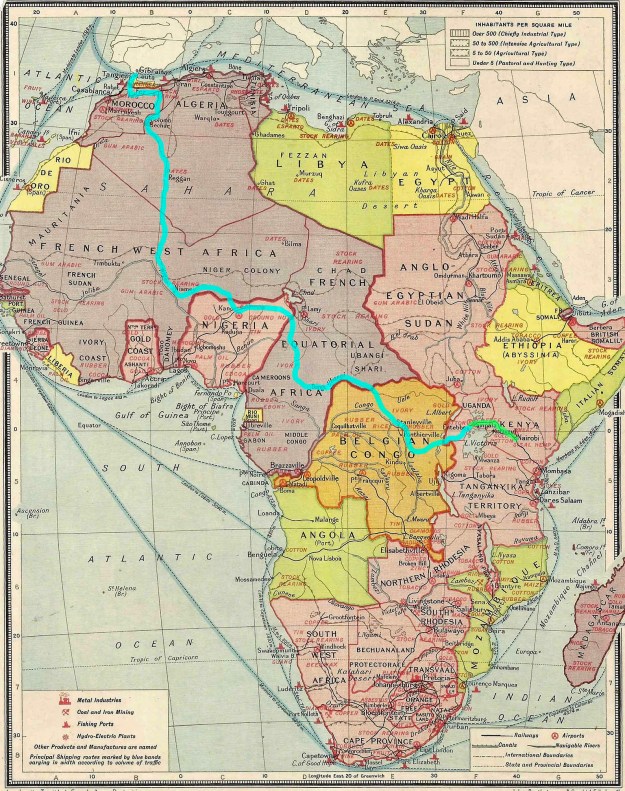

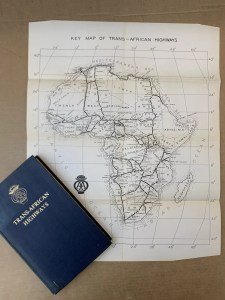

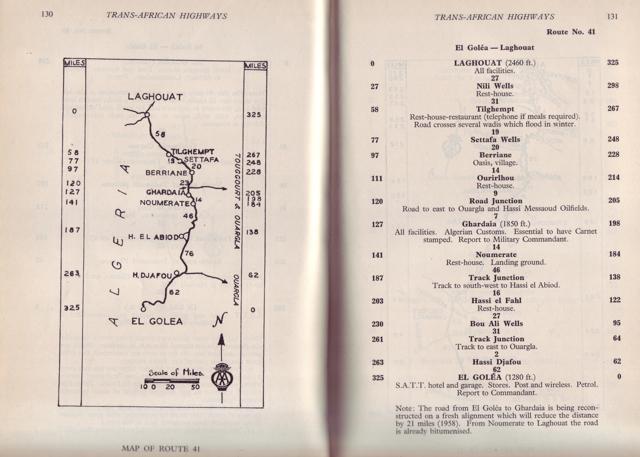

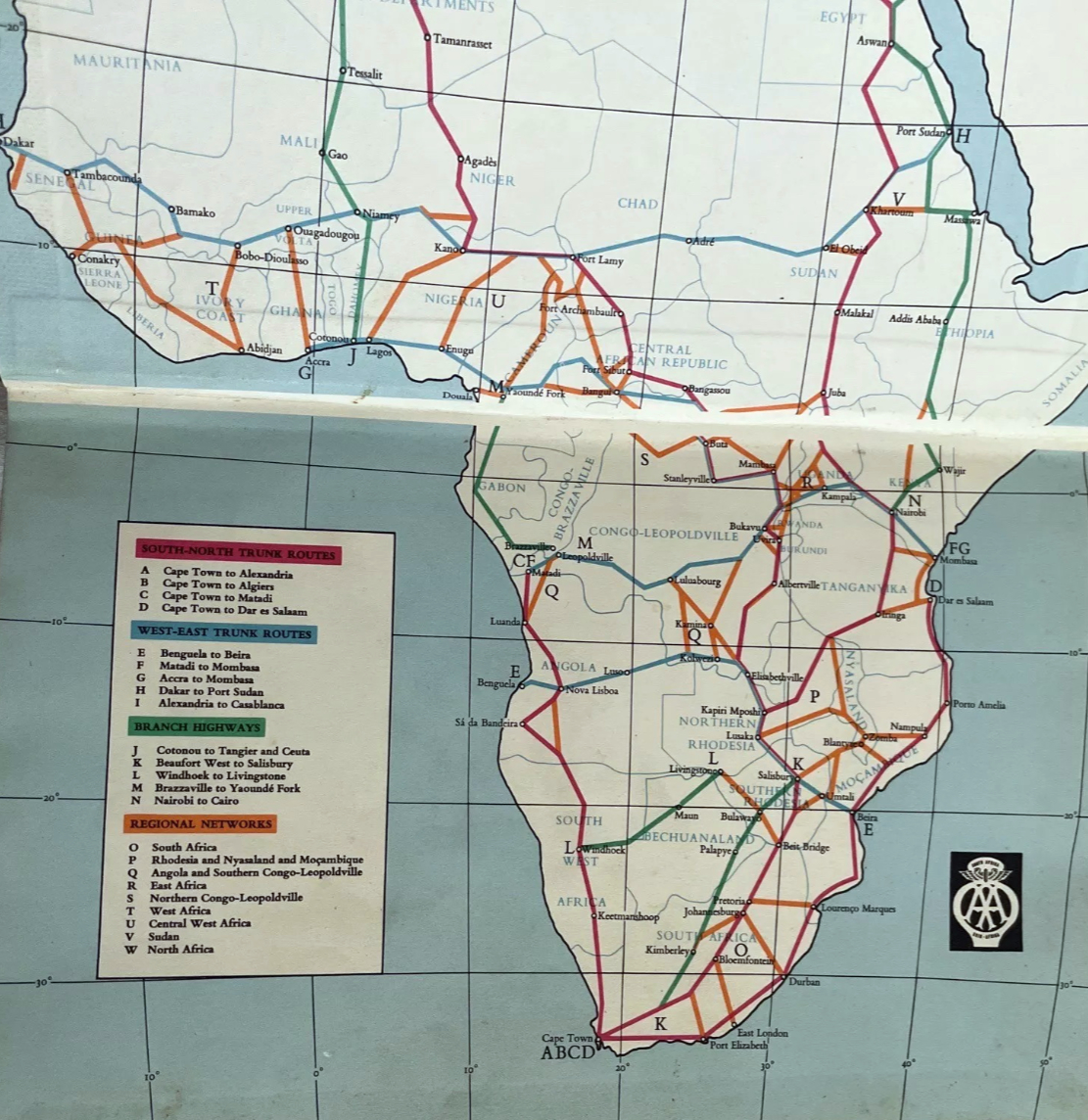

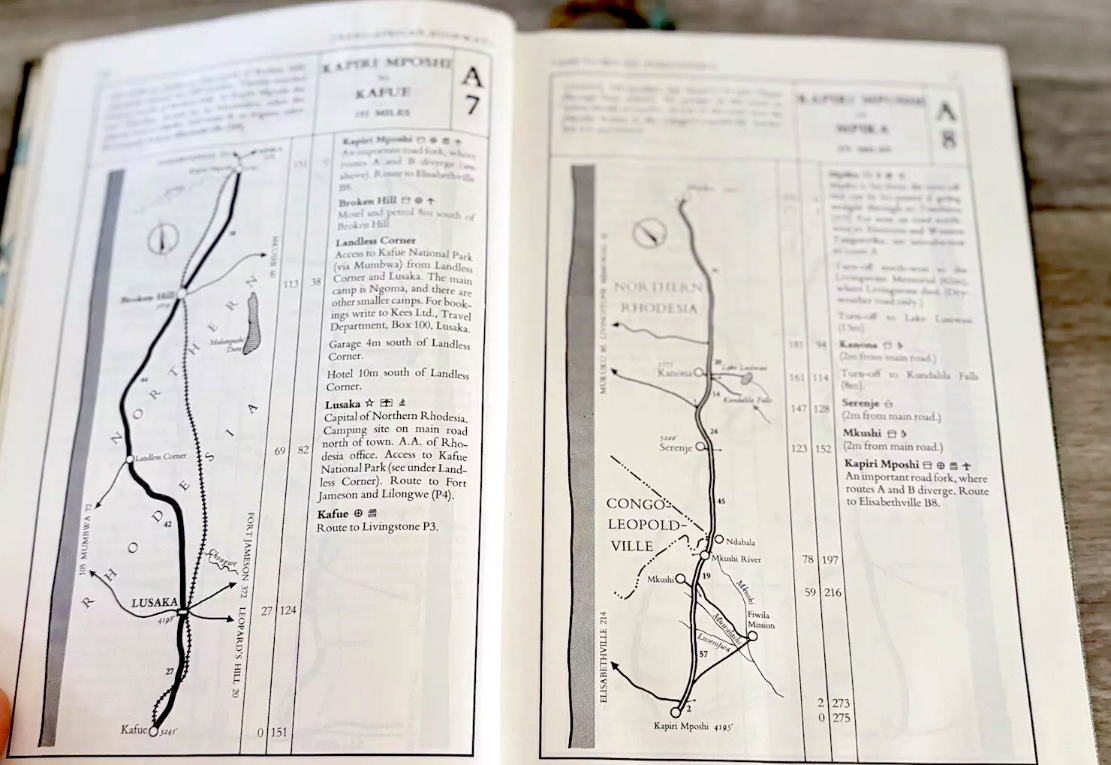

The Trans-Africa Highways route guide (below) was first published in 1949 by the Automobile Association of South Africa. There are loads of copies online from £25: I bought the final, 5th edition published in 1963, by which time the vast majority of the European colonies (list with dates) were independent. The preface to the 5th edition explained the laborious task of redrawing all the guide’s maps to conform with the new nations. The guide closely resembles the French Shell Guide to the Sahara published since the mid-1930s: page after page of annotated strip maps along a given route. Knud and Svend used the 1949 edition of Trans-African Highways which Anders still owns.

In 1954 two Danes, Knud Jensen and Svend Nielsen, drove a Morris Oxford from Kampala Uganda through equatorial Africa and across the Sahara to Kvistgård in Denmark. The 14,373 kilometre adventure nearly cost the lives of all three.

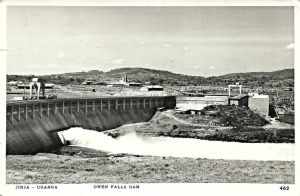

For three years, Knud and Svend had worked as carpenters for Christiani & Nielsen on the construction of the Owen Falls Dam (left) in Jinja, Uganda. This is where the Nile flows out of Lake Victoria to continue north to the Mediterranean. [An old treaty between Uganda and Egypt endured the Nile’s flow was unaffected, though during the 1956 Suez Crisis the Brits considered cutting the flow so to oust Nasser, even at the cost of flooding around Lake Victoria.]

Along with their last salary, they received two plane tickets back home to Denmark, but they chose to cash these in instead. The two young men decided to drive home to Denmark. Knud had an almost new Morris Oxford [Series MO, left] and when you’re young, the spirit of adventure trounces reason.

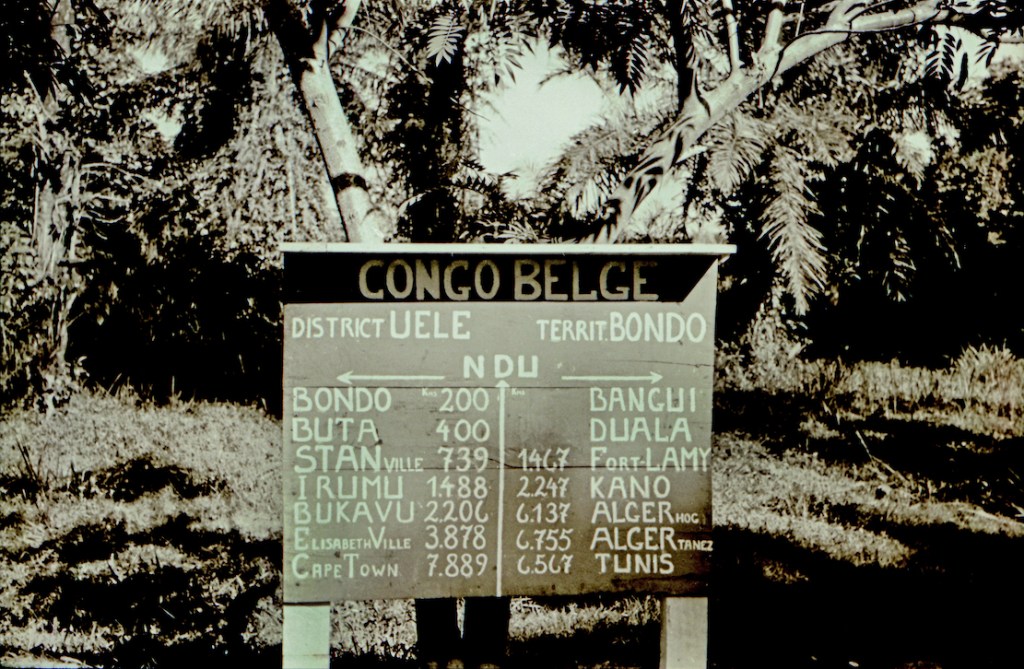

The direct route was via Sudan and Egypt [with the option of putting the car on a train across the desert from Khartoum to Wadi Halfa], but Egyptian President Nasser was in the process of kicking the British out (the Suez Crisis occurred in 1956). Meanwhile Sudan was also wearying of the British and refused permission to transit the country. The only alternative led west across the Belgian Congo [today’s DRC] and on through French Equatorial Africa [CAR, Cameroon], British Nigeria, French West Africa [Niger] to Algeria and Tangier in Morocco.

The expedition required a huge amount of planning. Were there reliable maps? What were the roads like? When would the rainy season flood the rivers? What documents would be needed? Would the Morris even survive the trip and what spare parts would be needed? The 406-page guidebook, Trans-African Highways (left), published by the Automobile Association of South Africa, provided many answers.

The rainy season in central Africa began in April, and the route through the Sahara would be closed from June to October due to sandstorms and intense heat. This still gave the pair a few months to get organised. Costly permits to pass through French territories were obtained in Nairobi, Kenya – a round trip of nearly 1500km along wretched roads. In Kenya, the Mau-Mau uprising was underway, resulting in a driving ban after sunset. Knud recalled stayed overnight in a small hotel in Nukuru, where the white guests were hanging out in the bar with rifles close at hand. In another town, the police station had been burned down.

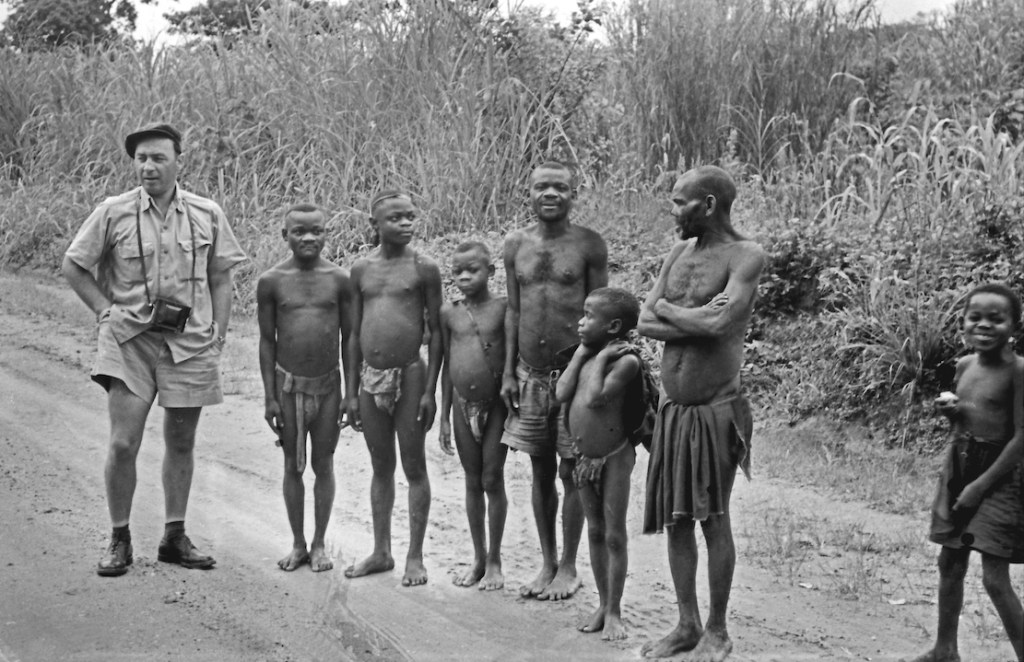

Back in Kampala, the Oxford was given a major makeover, and many spares were thrown into a back-up engine sump, which produced a metallic clatter all the way to Denmark. The spare sump served as insurance against a possibility of damage on rutted tracks. An auxiliary petrol tank was fitted in the spare wheel well, and four spare wheels were lashed to the roof rack. Typically, the car did not get a single flat, even though they didn’t see asphalt until they reached Morocco, 8000km later. With a Danish pennant on the left front fender, Knud and Svend left Kampala on 3 April 1954. Ahead awaited massive rivers, equatorial jungle, harsh desert, isolated tribes and miles of rough tracks.

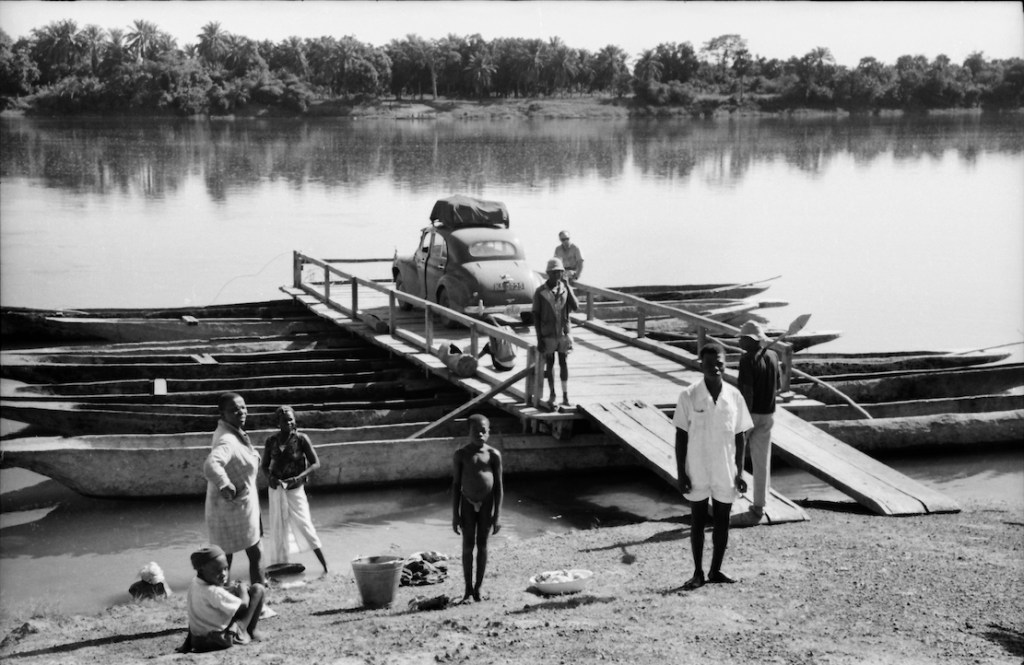

Soon they entered the Congo, where a rebellion against the Belgian colonial rule was already smouldering. But Knud and Svend were more concerned by the Pygmies’ evil glances. The road passed through dense jungle, and several rivers were crossed on small barges made of joined-up dugouts (below). The propulsion was a rower in a canoe on each side, directed rhythmically by the captain’s drum.

Kudu encounter

While still in the Congo, one of the Oxford’s front axles broke. The two had agreed they’d take turns in getting help so with the axle under his arm, Svend got a lift to the nearest town, while Knud set up camp in a clearing. The natives gestured loudly to move the tent, but Knud refused, assuming they were trying to lure him away from the stranded car. That night he found himself camped in the middle of a forest full of snorting, growling and unnerving brushing against the tent, but otherwise the parade of unseen beasts passed without incident. The next day the locals returned to see if he was still alive. Knud emerged from the tent in good form.

A few days later the Morris hit a kudu (a large, spiral horned antelope). The kudu trotted off unharmed, but they did not. The collision had shoved the fan back into the radiator leaving them to repair the damaged cells ‘the African way’. Being carpenters, they figured out how to knock some wooden plugs into the radiator at the bottom and squeeze the cells together at the top so water still flowed through. Miraculously, the repair lasted until they replaced the radiator in Spain.

In French West Africa [Niger] they ran out of drinking water. Thirst became such an acute problem they drew lots to see who’d try some murky ditch water. The idea was that if the one who drank got sick, the other might be able to continue. Knud was given the honour of the dirty water, filtered through a handkerchief soaked up with red wine to cover the bad taste, while Svend had to make do with a mouthful of wine every now and then. The days passed, and when they finally found fresh water, Svend was so dehydrated he was hallucinating.

On the verge of giving up, they were under pressure to cross Nigeria before the rainy season broke. In Niger, the U-bolts holding one of the rear leaf springs snapped. According to the map, the nearest town was at least 60km away and the temperature was reaching 45°C in the shade. Now it was Knud’s turn to seek help; a truck gave him a lift to Dosso which in 1954 turned out to be just a junction. The next day he got another lift to Niamey, Niger’s capital, but it being the weekend, everything was closed. On Monday, he finally managed to get a workshop to fabricate two new U-bolts.

Knud had wanted to wait until the next day, but realised Svend would have been impatient after waiting five days in the bush. The truck Knud returned on was the only vehicle Svend had seen in all that time, and he didn’t want to rot there any longer. While waiting, he’d crawled under the car for some respite from the heat, but the next morning found his body covered in rashes. Unfortunately, he’d shared his space under the car with a dozen rats.

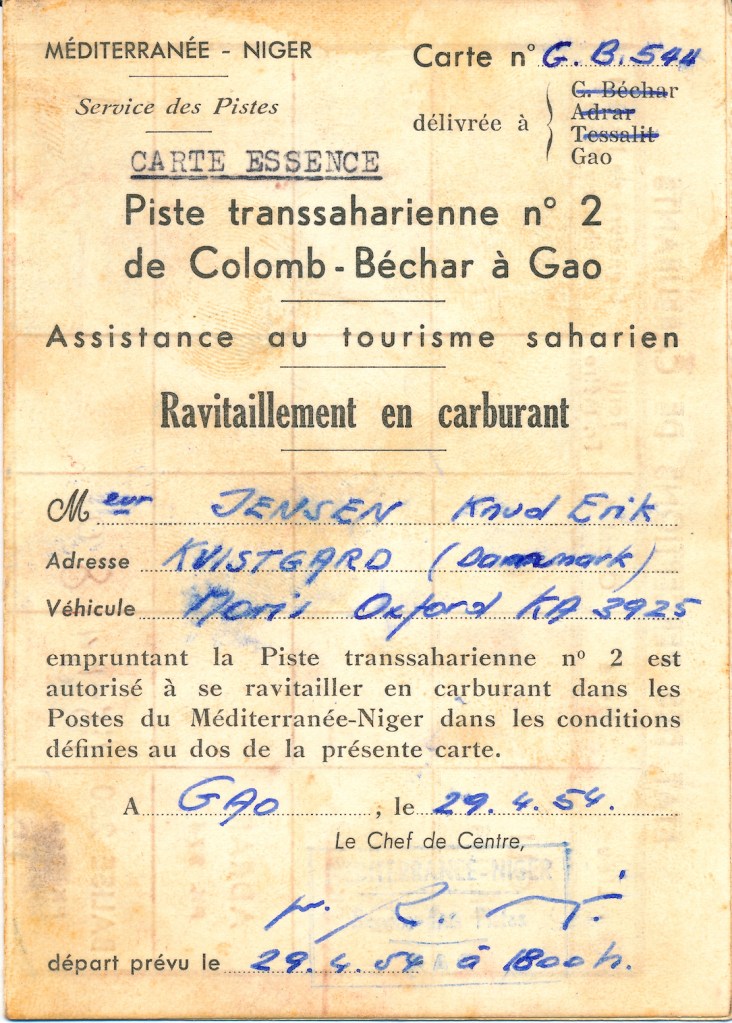

After 6000km and three weeks on the road, the two exhausted Danes reached Gao on the Niger river [present day Mali], the southern terminus of the 1800-km Tanezrouft piste across Sahara to Algeria [the route of the original crossing of the Sahara with

Citroëns in the early 1920s]. Here they met four Englishmen in a well-equipped 4WD, one of whom was a mechanic. They’d driven up from the Gold Coast (a former Danish colony, today Ghana) but had already blown four tyres. Although their original plan had also been to cross the Sahara, they’d lost their nerve and planned to sell the car and fly home.

This encounter made a sobering impression. Here they were stuck with an ailing ordinary family car with a broken rear spring, unstable steering and wheel bearings grinding with sand. Crossing the vast Sahara suddenly seemed like a daunting prospect. The only problem was the price they’d get for the clapped-out Austin wouldn’t even cover a single flight home. In silence they tried again to secure the broken spring by wrapping the handbrake cable around the broken leaves along with a pair of old trousers. At first glance, the repair seemed adequate.

Crossing the Sahara

With permission to cross the Sahara came a requirement that the police in Gao verified at least 60 litres of drinking water was carried. However, the police did not seem so bothered in how careless travellers might be, so most of the water reserve was replaced with petrol as fuel was expensive at the military checkpoints further north in the desert. These checkpoints were up to 400km apart and, according to the regulations, travellers had up to 36 hours to reach each one. If they didn’t show up, the military would launch a search at the drivers’ expense. However, one of the checkpoints explained this never really happened. Soldiers serving in the Foreign Legion had not signed up to be tourist guides.

The track through the Sahara was marked with single oil barrels [‘bidon’] every 2.5km and two stacked barrels every 5km. The sand-blasted wrecks of vehicles from unsuccessful transits also helped mark the route. For the first few days the track was corrugated – not so easy with a broken rear spring. Later they entered areas of loose sand which they tried to avoid while keeping in sight of the bidons. It became a struggle to shovel their way free, and the camaraderie became strained. When they got badly stuck for the third time on May 1st, Svend threw away his shovel and refused to work – this being International Workers’ Day. Knud assured him it was hardly likely the Danish Carpenters’ Association would find out about his shameful betrayal of the proletariat.

Despite these challenges, the journey through the harsh and beautiful landscape was a memorable experience. The great silence when they took a coffee break or ate beef straight from the can was indescribable. Then they’d sit in the sand with their feet in the ruts while the fiery red sun set, as it only does in Africa. When they got tired, they would burrow into the sand and look at the billions of stars overhead.

Major repairs in the Sahara

Every now and then the engine would cut-out due to vapour-lock in the fuel pump struggling in the immense heat. Cooling it with a wrapped wet cloth helped a little, but the engine was also losing power and knocking loudly until they could only run for 3km at a time. Now the spare parts they brought from Uganda became invaluable. The engine was removed and disassembled in the desert and a destroyed main bearing was was replaced with a lot of filing and hammering. It took hours, but when the car started on the first try, the proud smiles lasted the rest of the day. The broken spring still had to be re-tied constantly, but after seven days they finally reached Reggane with a hotel and a proper meal.

Finances were tight if they were to get home. In Nairobi they’d paid a deposit of £1000 for permission to cross the desert, which they could claim back at any French government office north of the Sahara. But in Colomb-Bechar they didn’t have pounds. A detour was taken to Oudja in Morocco, but the consulate was closed, and the following day there were violent anti-French riots. And when the consulate finally opened, they didn’t have any pounds either. In Tangier it was the same story, and the Danish consulate could not help.

In the end, by exchanging their remaining African currencies, they were able to buy a ferry ticket across the Straits of Gibraltar, then at least they were in Europe. In Malaga, Svend sent a telegram asking for money, and while they waited, they stayed in a small hotel in town. The money took three weeks to arrive, and by the time the hotel bill was settled, there was barely enough left to reach Denmark. In Madrid, they pawned binoculars, cameras and a tent to get a little further north.

Late one evening in Germany they were stopped by the police on the Autobahn because both rear lights were out. They promised to fix the mess at the next fuel station, unable to admit that both headlight housings were rattling around in the trunk. To their great frustration, they only had enough fuel to reach the border in Kruså, but the Danish customs officers showed a rarely cheerful side. Despite the early hour they were fascinated to learn of the duos’ arduous adventure from Uganda. And when Knud and Svend explained they had to wait for money for fuel, the customs officers offered to lend them the cash so that they could drive home.

The two adventurers never forgot their welcome to Denmark. In Hillerød they sat in silence for half an hour, looking across the lake towards Frederiksborg Castle. It was June 5, 1954 – two months and two days since they’d left Kampala, and a beautiful summer day. It was hard to believe the adventure had reached its final chapter. Twelve minutes later, they rolled up in front of Knud’s parents’ house in Kvistgård, where the mother came out onto the steps, clapped her hands together and exclaimed: “Well, you’re finally here – you must be very hungry!”