Aïr and Tenere

Tony and Elly van Gastel

Surfing the Internet produced many disturbing messages such as:

“Avoid the tracks round Agadez absolutely”

“Tuaregs steal cars”

“An Italian died who was hit by a bullet between Niamey and Agadez”

“Police are corrupt and arrogant”

“It’s dangerous to travel in Niger”

“Only travel in convoy with a guide is allowed”

Then we contacted several people for more information. Here are a few of the responses:

“I can – with complete peace of mind – invite you to visit this wonderful country.”

“A lot of people will spend the new millenium in the desert.”

“There is still some risk, which can be minimised by hiring an experienced guide.”

“Bandit Tuaregs steal cars, if you are not accompanied by a Tuareg guide. If this happens, give up the car. The Italian who died, refused to give up his car and raced off.”

“Two cars are not really a luxury, but a safety measure.”

Based on these responses Niger’s Air Mountains and Tenere Desert was on.

To arrange a guide, we tried to contact several travel agencies by fax. We got only one reply and the agency wanted to charge 70 FF/per person/per day. While we were in Niger, we realised that travel agencies are not interested in providing a guide only; they like to arrange a complete package, including cars, tents, food, drivers, guides, etc. In the end we arranged a guide through friends in Niamey (using e-mail) for which we paid CFA 24,000 per day for the group.

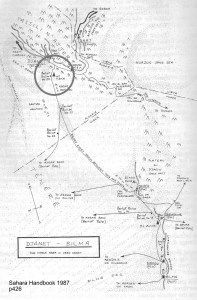

The trip would take us from Agadez into the Air Mountains (Elmeki, Timia, Assode, Tchintoulous, Zagado valley) and then to to the Arakao Crater, Adrar Chiriet, Tezirzek, and Temet. Then back via Iferouane to Agadez.

On December 21, 1999 we departed with 5 persons in 2 cars (one Toyota Landcruiser and one Land Rover Defender 90) . It took us 4 very long days to get to Agadez (2500 km from Accra). We had a few problems on the way, which almost made us abandon the whole trip. Just before Bolgatanga, the Land Rover developed an electrical problem. The car had been in the workshop in Accra for exactly the same problem and it had taken 4 days to rectify it. We were worried that nobody would be able to fix this in a ‘remote’ area like north Ghana. We all had visions of an early end of our desert trip. It appeared a fuse, which kept on blowing and we fixed it by putting a 20 amp fuse instead of the recommended 5 amp one. We all hoped that this would keep us going. And it did!

On on to Niger

All the way from Accra the road had been good, but immediately after the Burkina Faso border with Niger the road deteriorated enormously. We had our next serious problem when the Defender’s roofrack came almost off the car. It jumped out of the gutter of the car, after the mounts got completely bent. We moved the roof tent onto the roofrack of the Toyota and completely dismantled the 90’s roofrack. Three hours of hard work and we were on the road again. We spent the night at the completely empty ‘Niamey’ camping. We noticed that the temperature at night got cooler and cooler. We wondered what it would be out in the desert. We were not really prepared for cold weather. Next day we drove to Agadez (950 km), where we arrived one day too late.

Departure from Agadez

Our Tuareg guide had been waiting for us all day. The travel agency insisted we must carry 285 litres of diesel per vehicle, when leaving Agadez. Fuelling and stowing the 570 litres for the two cars took quite some time. With four persons (including the guide) in our car, 285 l of fuel, 80 litters of water, the luggage, spare parts, sand ladders, spare tyres and food, the car was fully loaded. We wondered how it would be able to travel through soft sand.

The travel agency had arranged the travel permit for our trip. It seems that unauthorised travel is not allowed.

We still had another problem. Our Laissez Passer would expire before returning to Agadez. At the border they could only issue a Laissez Passer with a validity of 7 days. We discussed this with the travel agency and they would arrange the ‘prolongation’. They kept the original and we travelled with a copy. They advised us to give a little ‘cadeau’ to police officers, when necessary.

It was completely dark when we finally left Agadez. We camped approximately 6 km out of Agadez.

Christmas in the Air Mountains

The track was going through the typical transitional zone between the Sahel savannah and the real desert with a few bushes. Occasionally we had to cross a very sandy wadi (4WD necessary). Along the wadis, where the water is not far down, sedentary Tuaregs have their ‘jardins’ (gardens), were they grow tomatoes, onions, peppers, and dates. Soon the track became stony and small, completely barren hills could be seen in the distance. Then we drove on a plateau (500-600 m high) with black basalt hills all around us.

We met several Tuaregs on their camels and took many photographs. The mountains got higher and more impressive. We stopped at one of the ‘jardins’ to see how they use a camel to pull the water from a waterhole to irrigate the field.

The mountains were now almost completely barren without any vegetation, except along the wadis. At one time we went up to almost 900 meters. We spent the night in a beautiful wadi with trees to protect us from the cold desert wind. We all enjoyed the Christmas dinner of baked beans and a bottle of wine. In the evening a nasty cold wind started blowing and we changed into long trousers, extra pullovers and shawls. Our guide Ahmed told us that this would be only the beginning; it would be much colder once we were out in the real desert.

Next day the route continued over a plateau; sometimes stony, sometimes less, always with beautiful black or reddish mountains around us. Occasionally we had to climb a hill. In the village of Kripkrip we saw again a lot of ‘jardins’. We climbed up to almost 1000 meters before descending to the village of Timia. Just before Timia, in the middle of a very stony area, is a small waterfall. It must be fun to take a swim in the small lake when visiting the place during the hot season (if it has not dried up by then).

Timia is a real oasis. An restored fort from the French period is overlooking the wadi and the village. In the background is the peak of Adrar Egalh (1974 m). Everywhere are ‘jardins’ along the wadi. From the waterhole of one of these gardens we replenished our water supply. From Timia, we continued to the ruins of Assode, the old capital of the area some 100 years ago. Only some remains of walls are left. The area is littered with pottery sherds.

We then followed the Zilalet wadi. Far in the distance is the Agueraguer mountain (1730m) with the village of Tchintoulous (not more than a few huts; but quite a number of gardens) at its foot. A few kilometres east of the village we set up camp for the night (altitude 875m). Empty plastic jerrycans were given away to the occasional ‘visitor’ of our campsite. Often they ask for medicines and small gifts are always welcome. That evening a very cold desert wind kept the temperature low. We slept in our sleeping bags with all our clothes on. Next morning it was approximately 5°C (Brrrrr).

Through the Zagado Valley to the Tenere Desert

We would finally go to the real desert; the Tenere. First we drove through the Zagado valley. Very sandy but with beautiful white sand and with black mountains at both sides. Then, slowly we drove away from the Air Mountains and entered the real Tenere. The scenery is exactly as you see on photographs; endless undulating sand hills, devoid of any vegetation. Nothing to see, but unbelievably beautiful. We spotted a desert fox. We had to use 4WD all the way. The route goes uphill and downhill; kilometre after kilometre. The guide warned, that we had to be careful when driving uphill. Before descending you have to ensure that the wind has not converted the sand dune at the backside into a descent too steep for cars.

Arakao Crater

We had to negotiate a lot more of soft sand before reaching the huge sandy Arakao Crater with a diameter of 10 km and rock formations around it. We made camp at a beautiful location. Ahmed had warned us that it would be cold, since we were now in the desert. We, therefore, collected lots of firewood and lit a fire when it started to get cold. It became colder and colder and next morning it was below zero degrees.

We were only one week from home, but felt that Accra hardly existed and that we were away from all civilisation. In the morning we got the fire going again, had hot coffee and prepared for departure. An Egyptian Vulture was soaring overhead. The Toyota battery did not seem very happy because of the cold, but the car did start (only just).

Adrar Chiriet

We were driving along the Taghmert (1637m) in the direction of the Tamgak (with peaks between 1600 and almost 2000m), when we passed a group of camels, carrying the baggage of a group of tourists, who were making a camel tour.

Somewhere at the foot of the Taghmert we drove to a waterhole to replenish our water supply. Then we followed the Wadi Tchou-m-degdeg in a northerly direction. At last we turned east and drove straight towards the Adrar Chiriet. It looked like an 8 lane highway; completely flat and you could drive were you wished. We made camp in the centre of the mountain, under one of the few trees that could be found. We pulled a big dead tree to the campsite, so we would have a fire to keep us warm in the evening.

Rock Engravings

Early in the morning we drove back towards the Tamgak. The sun was still very low, and drew fantastic shadows on the sand dunes; we do not make much progress, because we made one stop after the other to take photographs. This really was worth all the trouble (mainly the cold) we had gone through. We were now on our way to the rock engravings in Tezirzek. Several articles with beautiful pictures have been published in the National Geographic over the past few years. It was impressive indeed.

Temet

After Tezirzek we headed for Adrar Greboun with peaks between 1500m and 1950m. When leaving the Greboun behind, it becomes more sandy and the scenery gets better. When reaching the Col de Temet, we were surrounded by 200-300 meter high sand dunes. Beautiful, the best we had seen so far. In this superb setting, we made camp. The altitude was 950m; the temperature still 27°C. We climbed one of the high sand dunes, a tough job; there are more sand dunes further afield, undulating like an ocean.

The day before we had seen our first ‘gazelle’ (Dorcas antelope) and we now saw many more. According to the books there are more species of antelopes around. At dusk we spotted two silver-backed jackals near our campsite.

Early next morning, we left our campsite. We reached Iferouane, a nice village, with only mudbrick buildings, where we had to report to the police. We worried a bit, because we only had a copy of the Laissez Passer. However, they only asked for the travel permit and we had to pay CFA 1000 per passport. Then 140 km over a dirt road and 185 km over an excellent tarmac road took us back to Agadez.

Agadez again

Agadez also has a mysterious connotation, like Timbuktu. An intriguing city, with mainly mudbrick houses and with a beautiful Sudanese-style minaret on the great mosque. Decorations on mudbrick houses and doors are, however, minimal. Still, it is good to wander around in the old city, where it seems that time has not moved much. The famous Air Hotel is supposedly the place to be. The hotel looks dilapidated, but sitting on the roof terrace and watching the Tuaregs go about their business is a nice experience. For the extension of the Laissez-Passer we had to pay CFA 10,000.

Back to Accra

In three days we drove back from Agadez to Accra. We had been away for 15 days, driven 6200 km and been in the car for 123 hours. For us none of the disturbing messages found on the Internet were true; police officers were correct and friendly, and we never had the feeling that it was dangeous. We had a very good time in Niger; it was the best trip we had made in the last 10 years. However, we decided never to travel in December ever again. It was just too cold at night!

Waypoints

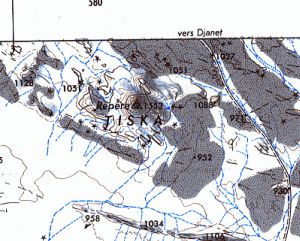

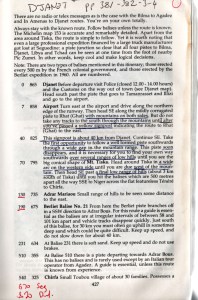

Where there was a clear track on the 1:200,000 IGN maps, we had entered the waypoints in the GPS before departure from Accra. These were generally accurate enough to travel without the help of a guide, which would have been more fun. However, the 1:200,000 maps do not show the track from Assode, via the Zagado valley, Kogo, Arakaou Crater, and Adrar Cheriet to Temet and it would not have been possible to do this stretch without a guide.