Part of the occasional Sahara A to Z series

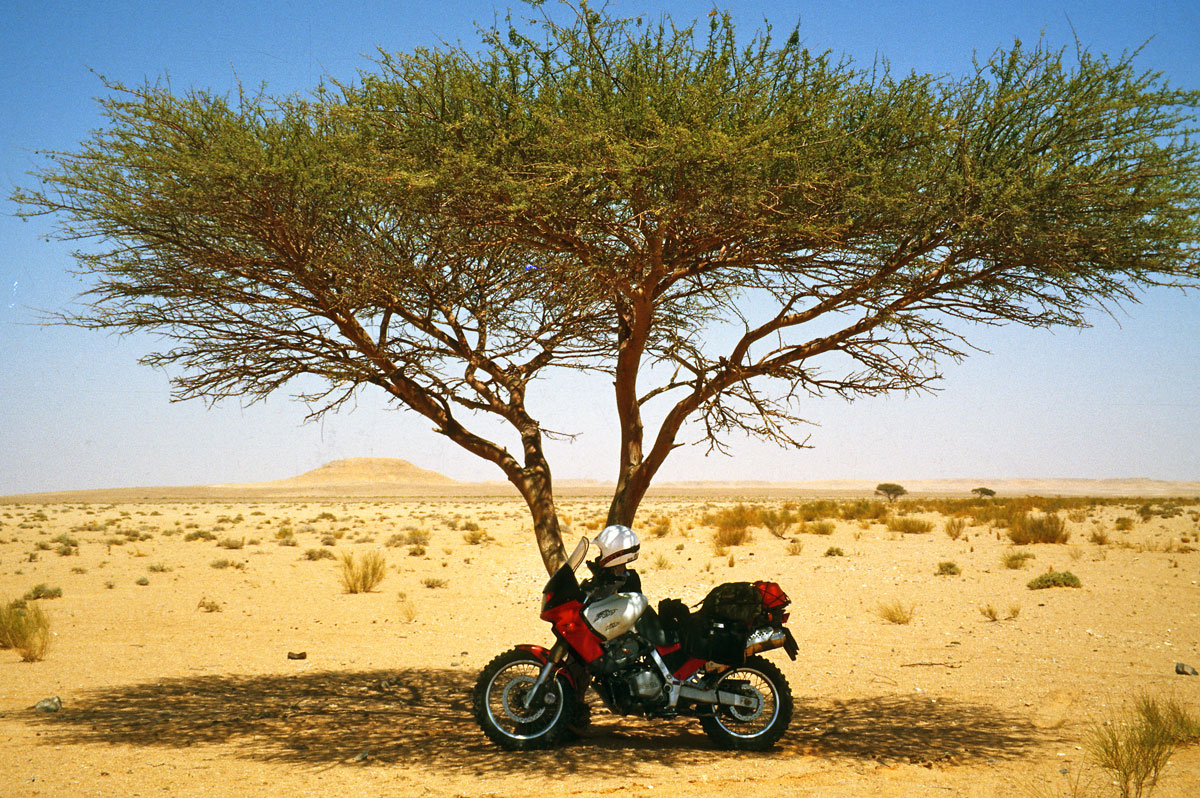

A 2008 BMW 650X was my 2014 project bike

Go to most embassies and at the very least you’ll find a few tourist pamphlets and a poster of a couple frolicking by a fountain. There was no such noncing about at the Libyan Interests Section in London’s Harley Street in the late 1990s. Down in the grubby basement mean-looking guys ground another fag into a Brit passport and ignored you purposefully. Tourist literature was limited to a defiant newsletter commemorating the ‘drawing of the Line of Death’ against imperial aggressors. Charming. Just the spot to enjoy a spring break on a bike.

‘Visa?’ I asked meekly. ‘Hello? Visa?’

It has taken me months to get to this point. In November 1997 with the third edition of AMH completed, I decided it was time to practice what I preached. Libya sounded interesting and BMW’s Funduro trailie would make a change from another Yamaha XT600Z Ténéré.

Buying a three-year-old F650 (bike #47) was easy; getting a Libyan visa involved countless dead-end faxes to various Libyan tourist agencies for the required invitation. Eventually, a mysterious internet connection provided an invite at a price and my permit was telexed from Tripoli in early April. A week later I was walking down Harley Street with the requisite stamp. There was no going back now.

I may have been nervous about my destination but I was less uncertain about the bike. I’d always fancied trying the Funduro. They came out in 1993, a trusty combination of Rotax engine and BMW build quality plus a naff name and a look unlike anything else. No one had anything bad to say about them other than being a bit heavy for off-roading. The revvy engine took a bit of getting used to after my torquey XTs, but with the right tyres I was sure the 650 would be up for some piste bashing.

As I was hard-up modifications were kept to a minimum – or that’s the excuse I give myself. Truth is the bike should need the bare minimum of adaptions.

A fat Michelin Desert was squeezed on the back after a bit of sawing at the outer knobs. The front end took a ‘rear’ 19” Pirelli MT21 with a lot more knob-chopping and fitting a mudguard off a Honda VT500. Road riding on these tyres was initially unnerving, especially the ‘marbles-on-glass’ MT, but I soon got used to it.

The bike had come with a new o-ring chain, some brand I’d never heard of, but I figured it would last the trip. The 27-litre Acerbis tank managed to look barely bigger than the original but promised a useful 500km range. To help work out distances in kilometres, BMW UK gave me a metric speedo which saved on possible errors when converting from miles to kms. A chunky alloy Touratech GPS bar mount held my snazzy new Garmin 12 firmly in place, and a cheapo ball compass was screwed on the dashboard. Lastly, I fitted an in-line fuel filter, a cig’ lighter plug for the GPS, fork gaiters and a high screen. It was March now, high time to head south.

To save my knobs I took the overnight Motorail from Paris to Marseille and then caught a ferry to Tunis where ensued five hours of messing around from one counter to the next. If this was Tunisian immigration what would Libya be like? And another thing troubled me: had I left it too late in the season? By now temperatures were climbing steeply right across the Sahara and with it, expected water consumption and a host of other problems.

A couple of months earlier a New Year’s meet up with a guy who worked in the Libyan oil fields actually put me off the whole idea. He warned me about the enervating ghibli winds which blew in April and melted strong men’s brains. A story of a guy who’d driven out into the storm sounded especially grim.

‘About a month after the guy had gone missing a nomad came into the camp and asked if we wanted to know where our Toyota was? We said yes and it cost us. Then he asked did we want our body back – it cost us some more. Turns out the guy had just parked up with the engine running and walked out into the sandstorm.’

With a weather eye out for the ghibli, by the next afternoon I was close to the Libyan border with a wodge of illicitly bought Libyan currency stuffed down my crotch. At the border I was again resigned to hours of shuffling from one hangar to the next, filling out forms and getting stamps. But by chance one of the many Libyan travel agents I’d given up on recognised me and whisked me through the formalities in just twenty minutes (and only a hundred quid!). Stunned at my good fortune, I set off towards Tripoli in the fading light and soon pulled over to fill the tank up for just 60p. That’s right: sixty pence. Super petrol works out at 2.5p a litre, or if I you’re feeling stingy, regular costs just 2p.

Dozens of the roadside wrecks traffic along Libya’s main coastal highway testified to the lethal mixture of ‘get-out-of-my-way’ gangsters in blacked-out Mercs and lopsided farmyard bangers piloted by granddad in coke-bottle specs. So after a night in the bushes, I was relieved to turn off the Death Highway south towards Ghadames, 550km away. Now the roadsides were only marked by posters of the Brother Leader, hands raised in a ‘we’re all in this together!’ salute.

As I rode into the desert on super smooth blacktop I wondered when the real heat would begin. I didn’t have to wait long. By mid-afternoon the temperature had risen to the high thirties and out of the blue the bike started spluttering. Surely I haven’t got through the tank already, I thought? Undoing the cap revealed plenty of gas. The bike started up but a few miles later cut out again. I got off, had a look at things and guessed the cause. A combination of half empty tank and minimal throttle at cruising speed added to the afternoon heat saw the trickling petrol evaporate in the added fuel filter and cause vapour lock – cutting off the fuel supply. Stopping cooled things down and got the petrol flowing again. Later on, when pouring cooling water over the filter body I saw the petrol level rise instantly, I knew I’d guessed right.

Knowing the problem was as good as solving it, so I filled up first chance and carried on to Ghadames, arriving zonked out at the empty campsite just as the sun set. Slumped out on the sand, I had a think. If it was reaching nearly 40°C this far north, how hot would it be further south? The vapour lock was easily fixed with a cardboard heat shield (above), but I was keen to get the BM on the dirt. Was I taking too great a risk riding alone? From here my plan was to ride across the Hamada el Hamra, or Red Plateau, then cut over the edge of the Ubari Sand Sea down to the Akakus mountains near the Algeria/Niger border, altogether about a week’s riding.

My French guidebook (all that was available) claimed the route across the plateau was a straightforward 450km gravel track with a well half way. Just about within my fuel range, though in these temperatures water consumption was another matter. I checked over the bike, wrote myself a road book and planned to leave early next morning.

That night at 2am a rising gale woke me and I dozed fitfully as the tent wobbled and the palms flapped overhead. Dawn revealed an orange sky and a thick dusty haze. Was this the ghibli I’d been warned of? I postponed my departure, hoping it would die down, but in the end set off back to the village of Derj where the plateau track began. I’d reassess once I got there.

Topping up at Derj junction, I was on the verge of heading back to Tunisia. As I sat there mulling over ‘dare I’ with ‘should I’, the attendant leaned out the door and said

‘Eh, la mangeria?’

La what? ‘Mangeria!’ He made the universal mime for chow.

‘Ah oui, merci.’

In the desert I find I automatically slip into French, but unlike Morocco, Algeria, Niger, Mali and so on, Libya had actually been an Italian colony – and even then, only briefly. That’s presumably where this slang for food had come from. As I ate my bowl of oily stew a little German Isuzu pulled in and, as always in the desert, we sized each other up. A brief chat revealed that Rainer and Katja were also heading across the Red Plateau and would be happy to have another vehicle along for safety [Katja took most of these pictures from the car with my camera but I’m sorry to say I have not photos of them].

The aptly named the Red Plateau, a barren, undulating prairie of rust-coloured gravel cut by dry water courses. Rising to 800m, my oilfield mate hadn’t much good to say about it: a pitiless void that was either freezing or baking and criss-crossed with enough tracks to confuse even the wily nomads.

Enjoying the security of another vehicle, it felt great to be on the dirt at last. By myself I’d have been gnawing my lip into a frayed pulp. Shod with uncompromising tyres the BM handled the 40-50kph pace well enough, and it was fun concentrating on the riding instead of sitting on the blacktop. As expected, I was a lot quicker than Rainer’s ex-trans African Isuzu, but I didn’t mind stopping and waiting. Their very presence made this whole excursion much less tense. But there was one thing which bothered me…

‘Rainer, shouldn’t we be at Bir Gazell well by now?’

According to my speedo the landmark should have been close.

‘Bir Gazell? No, that is on the direct route, we are taking the southern route.’ ‘The southern route?’

‘Ya. Here, look. It goes down into the Ubari Sand Sea, turns east and follows the dunes to Idri. My guide book says it’s much more scenic than the boring direct route.’

‘How far is it?’

‘Oh, about six hundred kilometres.’

‘I doubt I’ve got enough fuel to go that far, especially if the piste gets sandy.’

‘Are you sure that’s a good idea?’

We paused for a moment to consider the implications.

‘Well, I have some spare petrol, about six litres.’ said Rainer whose Isuzu was diesel. We topped up the bike’s tank and decided to take a gamble and press on.

But by late afternoon we’d got ourselves lost. The next GPS waypoint was through the hills to the south, but our track was now heading west towards Algeria, the wrong way. This is all part and parcel of Sahara travel so, not unduly worried, we made camp in a oued and resolved to head directly for the waypoint next morning.

Cross-country riding may sound fun on a trail bike, but in the desert it can be incredibly slow. Once you ride off tracks, however bad they are, you find yourself walking the bike down rocky slopes, blundering up dead-end valleys or edging towards drops. Even with an early start and the bike reconnoitring a way through the hills, it still took us till noon next day to cover the 14km to the waypoint and the route.

Having lost some altitude coming off the plateau, the day began to burn and as I feared, the plateau’s firm gravel turned into plains of soft sand. As all you beach racers know, soft sand has to be attacked standing on the pegs with a nailed throttle and eyes firmly fixed on the way ahead. There is no easy option: back off, the front wheel digs in and you’re off – go too fast and you risk crashing. I did my share of both and finished the day exhausted by more shades of soft sand than the Cote d’Azur.

By now I was already cutting into Rainer and Katja’s water reserves, so we needed to find a well. Their German guidebook identified a source 40km away. We located what seemed the right place and ploughed into the sands where the Isuzu soon mired. While they shovelled I headed over the dunes, riding the sandy banks in all directions just to keep from getting stuck. After a while I found the well – bone dry and full of sand, just like in the movies. This little excursion cost us two hours, a heap of energy and still more water and fuel. We flopped out under some meagre shade. No one said anything.

We moved on, at one point encountering the vile surface-crusted powder known as feche-feche. Regular bull dust is often mistakenly called feche-feche; it sounds cool and looks epic in photos but is just fine dust.

This was one of only two occasions I’ve ever encountered it in the Sahara. Often found on the edge of large sand seas, a hard pie-like crust forms and can support a vehicle. Or it might break though into the flour-like blancmange beneath. I spotted it too late, the gnarly tyred Funduro ripped through the crust and sank in, engine screaming in first gear as a 20-foot roost spurted up vertically from the back wheel. By paddling madly I just managed to regain firmer ground in time to grab yet another desperate slug of water.

By now every minor exertion demanded a drink and these exhausting conditions went on for hours. In this sort of terrain the Funduro was just plain old Duro. Sure, the engine was amazingly zippy on the highway, but it lacked the grunt needed to chug through soft sand. And as I’ve found before, the super stiff Michelin Desert might do the trick on a hefty Dakar racer, but even at just 7 psi and with the tyre creeping round the rim (I was trying the self tapers-through-the-rim trick), it didn’t flatten out enough to provide traction. Result: lots of wheelspin and wasted fuel for not much forward progress.

At dusk we located a proper well with a bucket and trough. We filled up everything with water while camels mobbed us for a hand out. Then, fit only to quickly cook up some grub, the three of us crashed out for the third night running. We all knew we’d bitten off a bit more than we could chew, but the end was surely in sight.

We got going early but by nine next morning the bike was halfway down a dune and out of gas. We’d seen no other vehicles since we left the highway at Derj, so there was nothing for it but to lug out twenty litres of water and watch the Isuzu chug off over the sands in search of fuel. With a bit of luck they’d be back tomorrow. I knew that lying still in shade was the best way to limit water loss, so I crawled under a make shift lean-to and waited.

The burning sun inched across the sky and the scorching wind peppered me with sand. Then, just as I began thinking ‘What if…’ a toot-tooting heralded the early return of the little Trooper. An hour or so down the track they’d chanced upon a date plantation where a guy had topped off a jerrican’s worth from his pickup’s oil drum.

I poured the fuel into the tank and we were on the move again, but now the riding became really hard as the track squeezed between the dunes and rocky outcrops. Again we found ourselves searching for wind-erased tracks or taking repeated blasts up boulder-strewn slopes that even the nimble bike couldn’t manage. We covered just 40kms, when the Isuzu got stuck on a dune we’d all had enough and called it a day. Hopefully another early start on firmer, night-cooled sand would finally get us to Idri. The Hamra wasn’t letting us go without a fight.

On the trail by 6am, another four hours saw us finally rolled into Idri, me caked in dust and all absolutely shattered. I felt like I’d done a four-day enduro on a heavy loaded bike in 40-degree temperatures. Hang on, I just did that! A week later I was still aching.

At Idri I bade farewell to the tough German couple and headed north, butt-, leg-, arm-, hand- and back sore after the 600km pummeling. Heavy winds prolonged my retreat and at one point I had the distinctly novel sensation of leaning out round a bend while braced against a 50mph crosswind.

By the Tunisian border that cheap chain was on the way out – and when o-ring chains go they go fast. Back across Tunisia, back across the Med, another Motorail to save the chain and a quick coffee in Paris.

By accelerating very, very carefully I just made it to the Channel, but after only 2000 miles of riding and with the chain adjusted as tight as I dared, 20 miles from London the sprocket turned into a greasy knurled disc. Any thighter and the chain would pull out the countershaft srocket so there was nothing for it but to hire a van to get the bike home.

Years later, on a ferry back from Tunisia, I met Gerhard Gottler, the author of the German guidebook for Libya which Rainer and Katja had used. I explained how we’d struggled on ‘the southern piste’ (route ‘A9’ in his book), the waypoints didn’t join up and neither did the tracks.

“Route A9 is not a piste for beginners.”