A short photo and video commentary of this trip appears on the Desert Driving dvd. Additional maps at the bottom of the post

of this trip appears on the Desert Driving dvd. Additional maps at the bottom of the post

Part of the occasional Sahara A to Z series

Hang around long enough and you’ll get the full set

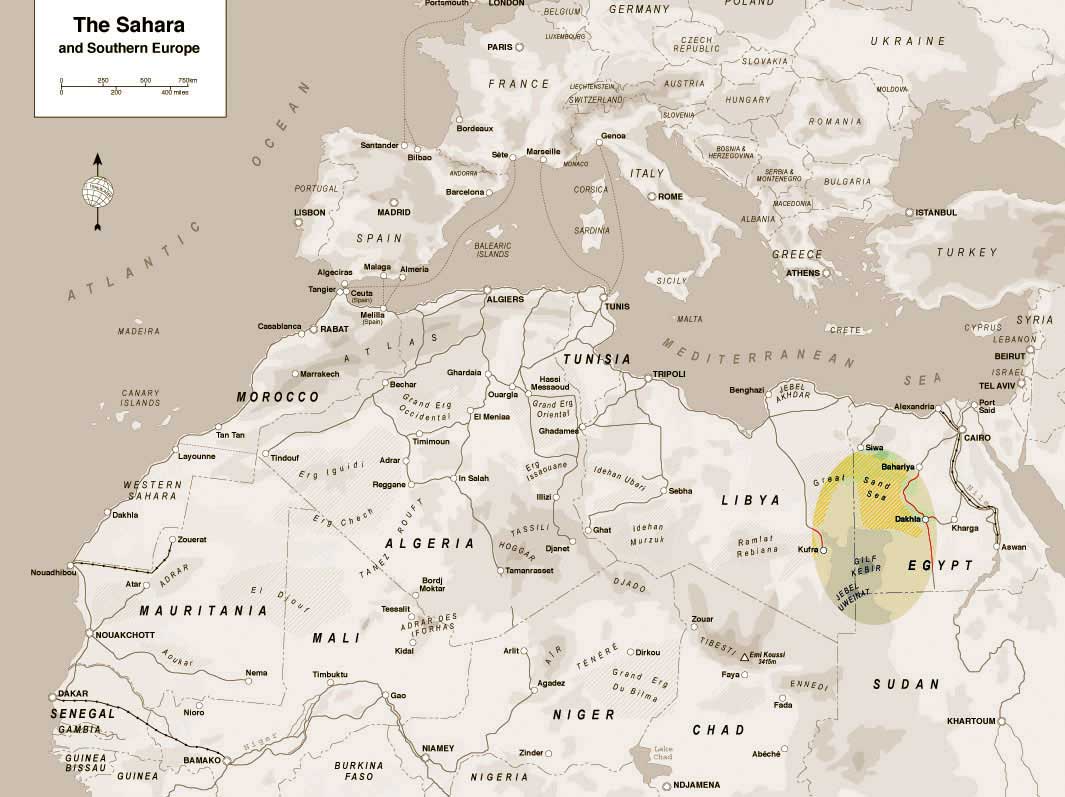

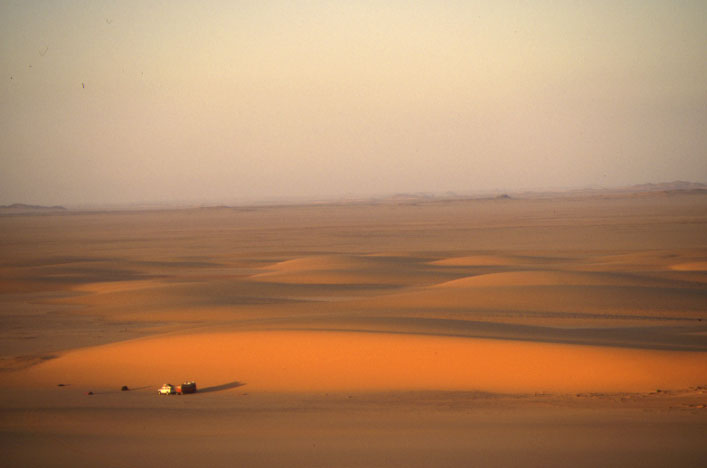

What sets the Libyan Desert apart is that it is ten times more arid than the rest of the Sahara: the Libyan Desert is the über Sahara. In an area the size of the UK through which we’d be travelling there is just one usable well and that single well outnumbers the permanent population. Looking out my window I can see more trees than we saw in two weeks and 2500km of travel. Even by Saharan standards, the Libyan Desert is extreme.

Abbreviated to ‘the Gilf’, the Egyptian part of the Libyan Desert is a mini Sahara in itself, encapsulating all the archetypal desert landforms. The Great Sand Sea lived up to its name, a dune field 200 kilometres wide and 600 long with dunes 200-feet high. It was here where the earliest experiments in driving cars on sand were made in the 1920s by the likes of Clayton and Bagnold (left). Its southern edge spilled over the massive Gilf Kebir plateau only discovered by Egyptian explorer Kemal el Din in 1925 using Citroen half-tracks.

South of the Gilf a sand sheet led to the isolated mountain of Jebel Uweinat which sits right across the borders of Egypt, Sudan and Libya. Our 2003-4 expedition was to last a fortnight and cover some 2500 kilometres. The plan was to pass down the east side of the Sand Sea to the Gilf, explore its eastern valleys and push on south to Uweinat mountain which we hoped to climb. From there we’d head back up to the southern cliffs of the Gilf, visiting the real Cave of the Swimmers made famous in the English Patient movie, and then skirt up the western edge of the plateau and plough through the heart of the Sand Sea for a couple of days to the oasis of Siwa, famed since the visit of Alexander the Great.

Our crack team of Saharaholics included photographer Toby Savage who co-presents my Desert Driving dvd, Dr Kevin White who’d worked with Toby on the Fezzan Project in Libya over several seasons searching for prehistoric lake beds, and Oxford climatologist Richard Washington whose bedtime reading included Applied Principles of Arid Zone Aeoleonics, or ‘dust storms’ to you and me.

We’d all travelled in the Sahara with our own four-wheelers, but shipping them to Egypt was never an option: too far, too expensive and, for the three weeks we’d given ourselves, bureaucratically maddening. Better by far to get Toby’s Egyptian mate Mahmoud to lay on three vehicles for the 2500km trip. Mahmoud already had plenty of experience exploring the area himself in his old Series III. For all of us used to looking after ourselves on our own desert trips, being pampered in this way was a bit luxury. Normally navigation, the vehicle, cooking and everything else would be down to us; on this trip we could sit back, enjoy the desert scenery and let someone else carry the load for a change.

A week before Christmas, Mahmoud met us at Cairo airport in a suped-up minibus and whisked us off for lunch on the Nile before we set off for the 400-km slog south to Bahariya oasis where the vehicles awaited us. On the way we speculated as to what those machines might be because, as I knew myself from a recce tour three years earlier, the ‘Gilf’ was tough on cars. Six hundred litres of fuel – 130 gallons per vehicle – was a typical payload, let alone food and water for a fortnight. We’d expect to see no one during out travels, with only the wadis around Jebel Uweinat offering the chance to replenish the single resource: firewood.

Driving desert highways at night is always a spooky experience. Small dunes shone in the moonlight and up ahead a cluster of lights signalled a lonely roadhouse, surrounded by trucks and vans serving the towns of the Western Oases. We pulled over for a brew to find everyone on both sides of the counter huddled around a dusty TV screen, On it a hirsute and spaced-out Sadaam Hussein was getting his gums probed by Special Forces, having just been dragged out of his lair.

Next morning in Bahariya we met up with Mahmoud’s pumpkin-bellied mate Loutfi who ran a local hotel and tourist excursions into the desert and nearby hot springs. Mahmoud and the vehicles were down the road a way: he had left before dawn for Dakhla to pick up the military escort which every tour in the Gilf requires. So we bundled into Loutfi’s 60-series Land Cruiser for the drive south to Abu Mungar and a rendezvous with Mahmoud in the desert.

All around us lay barren desert sands rimmed by the arching 600km escarpment that defines the Western Oases of Bahariya, Farafra Dakhla and Kharga.

In Pharaonic times what lay beyond was known as the Land of the Dead and even today, 5000 years later, the wilderness of dunes, sand sheet and rocky plateaux is still unpopulated, with just half a dozen towns of any size lay between ourselves and the Atlantic, 2000 miles to the west.

Loutfi’s 60 had just had an engine transplant, a grunty 12HT 4-litre turbo diesel, but by lunchtime it was getting distinctly hot. The needle was sitting in the red, there were burning rubber smells coming through the vents and the turbo was making an audible whine. Maybe this wasn’t the machine we’d be wanting in the Gilf after all.

Our quartet of backseat drivers watched the needle and muttered, waiting for the turbo or head gasket to blow. Loutfi pulled over to let the machine cool down and, once satisfied the needle had backed off, headed on south. Again the Tojo was cooking itself but Loutfi then confounded us by pulling off the road into the desert. None of us knew quite what was going on, but heading solo off-road with overheating problems seemed unorthodox. We churned over a few sandy passes, stopped off at the famous White Desert chalk outcrops and then bundled on to who knows where.

Presently we got back to the highway where Loutfi seemed unsure whether to turn left or right. He drove down the road a bit, looking out west, then turned back north. He spoke no English so we had no idea what was going on; had he lost something? Then he turned round once more, looking hard out to the west. He slammed on the brakes and did a U-ey. Ah ha, there it was: a hooned-out sand circle, a small cairn and three sets of tracks leading out into the void. Following these, within a few clicks we came upon a desert camp, the cars locked in the customary Gilf ‘U’ formation against the northerly wind. Mahmoud was there to greet us with smiley Ibrahim in his Bedouin head-dress, our ‘guard’ Hamed in a snazzy maroon shellsuit, Faraq the mechanic and Aisa, a cool dude in a pair of knackered cowboy boots and matching hat who was to be our cook for the next fortnight.

The identity of our three desert machines was revealed: Mahmoud’s Series III-bodied Toyota, a 110 Land Rover, which also had a 3.5 litre Tojo bus engine and gearbox, and Loutfi’s other car, a red HJ45, the old squared-off Land Cruiser from the late Seventies, but also with a newer six-cylinder 12HT turbo engine crammed under the lid. With potentially the best engine, the 45 was the load carrier; inside it, three 200-litre drums of diesel were lashed down with rope while on the roofs of all cars were additional jerries of fuel which, with the full tanks, added up to 2000 litres, more than enough for as many kilometres over the next fortnight. But with no car running an original engine or less than two decades old, we could see that spannerman Faraq wasn’t going to have a holiday.

That evening, in the cozy shelter of the U-camp, Richard and I keyed in our sat phones with Mahmoud’s so we’d have some sort of comms if we got separated and things turned pear-shaped. Mahmoud outlined tomorrow’s route: we were in the very edge of a series of parallel dunes running north-south; crossing the dunes would be impossible with the cars in their current overloaded state, but we could hopefully run down the 500m-wide corridors between the dunes as far as possible and ease over any low passes to gain ground to the west.

Next morning, knowing that things would get off to a slow start, Toby, Wash and I set off for a wander into the dunes to let the cars catch us up. After an hour there was still so sign of them, so we sat down on a high dune and scanned to the east, ears primed. Finally about 10am they turned up, having had problems getting one of the engines to fire up. We all hopped in and set off down the nearest corridor to see how far we could get. I was in the white 110 which inside looked like it had been a prop in The Birds, with every surface pecked to bits and wires hanging off the dash like splashed spaghetti. Still, the engine sounded good and it carried its weight well.

It didn’t take long before one of the vehicles struck trouble: the 45 had brake problems, but whatever it was Faraq fixed it in a jiffy and we moved on until the next: Mahmoud’s ‘Lanyota’ could not shift into low range. Faraq crawled in and tightened up the linkage with a bit of wire. The rack was also sagging in the alloy roof gutters which, on Defenders, means you can’t open the doors. (You couldn’t anyway as the door handles were buggered.) And the air bags which were backing up the rear parabolic springs were squeezing out like bars of wet soap.

These were fixed as best they could be and we moved on. Even in dune corridors the sand can change imperceptibly; one minute you’re clawing along at a decent pace, next thing the car sinks like a stone – but if you’re fast with the shifting and accelerator you’ll get through it. Momentum is the key to dune driving; once you’ve lost it you may as well pull up and put the kettle on. All of the vehicles got mired in soft patches several times and we all got stuck into pushing the cars back out, the quickest way of getting going if the driver has stopped early enough.

Part of the problem was that the Toyota gearboxes in the two Land Rovers were not optimised to the Land Rover axles, creating gaps in the gear ratios big enough to frighten Evel Kineval. Mahmoud’s Land Rover had an even more alarming habit of getting on two wheels while cornering hard, something which Mahmoud tended to do with gusto; I sure was glad I wasn’t in his car. By comparison, Ibrahim in the white 110 was a steady and smooth driver, never taking risks while struggling with the same mixed-up gearing and, it turned out later, no power steering.

By late afternoon we needed to get west, but high dunes were blocking the way. Mahmoud was nosing about for a way through but the heavy vehicles were struggling in the corridors, let alone trying to get up the sand banks. At one point Mahmoud took an oblique blast at a low dune but his angle was all wrong: halfway up, the wheels on the low side hit a soft patch and the vehicle keeled over to within a couple of degrees of tipping (it’s the front cover of Desert Driving). I knew from personal experience that these sort of recoveries where very tricky. Loufti’s 45 blasted up the dune to help and got mired too, but Ibrahim managed to get the 110 into position to fix a rope on the high side of the Leaning Rover. By backing up, the Series III was heaved up to a less jaunty angle and then, after a bit of digging and with Ibrahim holding it in tension, Loufti pulled it back down onto level ground. Back on the flat, Mahmoud spun round for a good run up, this time getting the wheels a foot in the air, and made it over. Me, I was happy to be in the car with Ibrahim behind the wheel.

That evening we camped at the cairn of Regenfeld, built by the German explorer Gerhard Rholfs in 1872, the first European to venture west into the Libyan Desert. It was here that his party gave up and turned north with their camels, weeks later reaching Siwa by the skin of their teeth. Rholfs left a message in a bottle in the cairn, and since then it’s been the custom for the few passing travellers to do likewise. We left our regards to whoever came next and then spent the night by the dunes as Rholfs and his crew had done 140 years earlier.

Next morning we carried on south and emerged from the dune corridors into a sandy plain dotted with cone hills; outliers of a long-since eroded plateau. One of these cone hills was Abu Ballas, or Pottery Hill. In 1912 the British explorer, Dr John Ball, discovered a cache of smashed clay urns at the foot or the hill and the truth behind an ancient local myth was revealed. Legends had it that for centuries the people of Dakhla suffered raids from “the black raiders from the west” even though everyone knew that ‘west of Dakhla’ was a waterless sea of sand, well beyond the range of a camel caravan. One day the Dakhlans decided to follow their tormentors into the feared desert. They never caught them but their tracks led to Abu Ballas hill and the stash of water urns. They smashed all the urns, destroying the vital water cache, and the raiders never returned, probably dying of thirst on their next raid. Today the remains of urns still litter the base of the outcrop while on its flanks delicate engravings of Ancient Egyptian deities survive.

Well out of the dunes by now, from Abu Ballas we turned west, following what might be called the only track in the Gilf, a braided network of ruts use by the occasional military patrols and exploratory tours like ours.

At one point we passed a perfectly straight line of 5-gallon Shell petrol tins, half a kilometre long. Marking a temporary WWII landing strip, these flimsy fuel containers date from the 1930s before the superior ‘jerrican’ was pinched from the Germans (hence “gerry can”) and adopted by the Eighth Army, LRDG and Halfords. Like the AK-47 or Douglas Dakota, the original jerrican is a functional design classic, unchanged and unimprovable.

Negotiating our way around low outcrops, isolated hills and small dunes ranges, our next destination was the Gilf Kebir plateau. By that evening we were close and camped in the lee of a dune close to Saviem Balise 22. Balise is French for marker post and in 1975 Saviem (later Renault) sponsored an expedition that tried to establish a new trans-Saharan route from the Atlantic to the Nile (see Sahara: West to East). About as useful as a fridge to an Eskimo, the Piste Saviem ‘from nowhere to nowhere’ was never used. All that remains today are the blue and white beacons they left to posterity along the way.

Leaving the lone marker post, we continued west and slowly, from the horizon’s haze, the low ramparts of the eastern Gilf began to rise. By mid-afternoon we were driving up Wadi Bakht, one of the three major valleys that drain their sands onto the plain. Six thousand years ago, during the brief humid phase before the Sahara reached its current state of desiccation, this valley was occupied by Neolithic hunter-gatherers, much like the Bushmen of the Kalahari. We camped that night at the site of a major Neolithic occupation, where we kicked up stone tools (above) and grinding stones (left) left by the ancestors of the pharaohs. It was a cold, windy night so Ibrahim grabbed an empty jerry and got a Bedouin singalong underway while we wrapped ourselves in everything we had and eyed-up Aisa’s bubbling stew longingly.

Having spent the previous night in one of the valleys winding into the Gilf Kebir plateau, we rounded a spur and powered up the sand banks to the dissected summit of the plateau. Some of the cars had trouble getting a good clear run and so to lighten the load we walked while they took a few runs. Approaching the plateau top required some hairy driving over nasty wavelets of sand and Mahmoud’s Land Rover was again getting on two wheels. We discussed what the cause might be and decided the vehicle was way over-sprung at the front. Throw in the more flexible parabolics plus a heavy roof load and it didn’t take much cornering force to get some air under the tyres.

We parked up near the summit where a cave looked out to the south like a gun emplacement. Inside, the ceiling was adorned with finely drawn beasts which would have grazed here 6000 years ago, something that was hard to imagine as we gazed out across the arid landscape of isolated hills and the distant sand sheet.

From the cave we descended the west side of the plateau and made our way south towards the Prince Kemal el Din Monument, a cairn built in 1932 by the real English Patient, the Hungarian explorer Laszlo Almasy, to honour this Egyptian royal who gave up the Egyptian throne for a life of freedom and desert exploration.

The monument is tricky to find, hidden among low hills, and as darkness encroached we blundered around looking for a way through. Suddenly our cars stopped; up ahead the drivers had spotted some lights below the cliffs that had gone out as soon as they saw our group.

The Sahara is still a wild enough place to be unnerved when you see other vehicles, and in places banditry prevails as it always did, but such encounters are unknown in the hyper remote Gilf. This lot appeared more nervous of us than we were of them; they were almost certainly smugglers. A lot of trafficking goes on between Libya and Sudan, avoiding the Libyan border posts around Uweinat by slipping through far to the south via Chad or around the Egyptian Gilf, as was happening here.

Mahmoud flashed his lights to draw them out and eventually a Toyota pick-up drew up out of the dark with a bunch of people perched on stack of drums in the back, wrapped up in blankets. Mahmoud had to coax them into talking as they were clearly edgy and wanted to press on, but once they realised we were just tourists and our military escort was packing nothing more than a notebook and a woolly hat, they relaxed a bit. The other two or three vehicles stayed out of sight. It transpired they were Sudanese guest workers taking a short cut home from Libya with more duty-free items than the transit lounge at Dubai airport. As soon as they could, they sped off into the dark to regroup with the other vehicles and moved on out of sight.

Next morning Richard and I walked the few kilometres to the monument on a GPS bearing and got there just as the cars arrived. Inside, just as at Regenfeld, an old tin contains notes from passers-by, including one of the old promotional stickers for my Sahara guidebook.

We turned southwest now for Jebel Uweinat, 150-km away, passing isolated volcanic craters poking out of the sand sheet like blisters. As we neared the mountain Mahmoud decided to skirt round the east side into Sudan to pay a visit to the Ain Murr well as our guard seemed OK about it. We spotted a long-abandoned border post right on 22°N, some old portacabins and other junk, and crawled through the rubble foothills until we were back on the sand sheet, with the fin-like outcrop of Jebel Kissu a few miles away. We turned west again and soon located the entrance to the shallow valley below the southern cliffs of Uweinat. As the valley narrowed and got stonier we passed some stone ruins and a stripped-out aeroplane fuselage. Once the cars could not continue, we walked on to discover the distinctly manky, algae-rimmed soak that was Ain Murr well – not a water source to rely on out here.

The bones of a dead Barbary sheep lay by the track and Ain Murr was the only place we heard the buzz of flies on the whole trip. Rubbish left by previous visitors underlined how much better it is to camp out in the wild desert. That night Aisa took even longer than usual to serve the meal, by which time some of us had turned in. But then again, he was up till 1am making his delicious flat breads, rolled out with a jack handle and fried on the lid of an old oil drum. Slow though he was some nights, Aisa managed to serve fresh food for the entire two-week trip, pulling it out from his various roof rack crates. I had endured awful food on my previous visit to the Gilf and Aisa’s far superior offerings reminded me that, just like an army, an expedition also travels on its stomach.

Near the camp we found a jerrican stamped ‘WD 1945’ and a pair of engine cowlings, probably part of the fuselage that later research revealed to be an Italian Savoia bomber sabotaged in 1942 during an LRDG raid when the place had been an Italian base.

We drove back round to the Egyptian side next day and into the much bigger valley of Karkur Talh. The valley is half blocked by a minefield, though why mine a dead-end valley with no water was anybody’s guess. Keeping a wide berth between us and the skull and crossbones signs, we powered over the sandy banks as Toby clung on in the back of the red Cruiser, doors flapping, to get some full-frontal action shots of the Rover-bodied cars.

Around here it rains about once a decade and the valley of Karkur Talh drains the entire eastern side of Uweinat mountain, the only haven of vegetation and talh or acacia trees in the entire arid expanse of the Libyan Desert. It wasn’t only us that appreciated it. Several thousand years ago Neolithic people grazed his animals here and, as at similar sites elsewhere in the Sahara, evidence of his life survives in the painted and engraved rock art on the cave walls and the odd stone tool.

A couple of us were hoping to have a crack at climbing to the 1932m-summit of Jebel Uweinat, a demanding two-day trek along whatever route the mountain offered. In a bit of a strop with his car, Mahmoud needed some persuading to continue up the valley far enough so we could have a shot at it, but as the sky lightened next morning, Richard and I strode up the dry creek bed with three bottles of water and a sleeping bag, soon followed by Toby and even Mahmoud who decided to come along too.

One of the big frustrations on this trip had been the slowness of the crew to pack up and get going in the morning. In the desert it’s customary to get up just after dawn and move off an hour or so later, parking up to enjoy some daylight before sunset. On this trip the drivers were still snoring away at 9am and, with regular problems getting one vehicle or another to fire up, it was always mid-morning before they set off. On Uweinat we were determined to seize the day!

This was all before the miracle of Google Earth so I carried a pixelated print of a sat photo showing a route taken a year or so earlier by another group which followed a likely looking valley up to the summit plateaux. Unfortunately I’d failed to lay an accurate long-lat grid onto this image and so, even with GPS, our position was just an estimate. In the end we started the day in Sudan, wandered north in to Egypt and, after an agonising late-afternoon up a boulder-filled valley, camped in Libya, about 500m below but still three kms direct from the summit – quite possibly the first people to camp there since the late Holocene. On the way up Mahmoud had discovered a new art site and our clearing even came with a bit of firewood. We were all knackered from staggering around all day on the rubble slopes and as the route onward was no less clear and would get much steeper, we returned to base next morning, getting back to the cars on the last dregs in our water bottles. The mountain would be there next time.

Uweinat was our southernmost point and from here it was north all the way, around the Gilf Kebir plateau to Siwa, still about 1000 miles away. We headed for the Gilf and the Wadi Sora cave, made famous as the ‘Cave of the Swimmers’ in the English Patient movie. As we neared the cave later that day we passed some clothes scattered in the sands, the remains of Somalian refugees who’d been dumped here by unscrupulous people traffickers while on their way to Benghazi and better opportunities in Europe. Loutfi had come across their bodies some months before. Besides the old favourites of guns and drugs, right across the Sahara it is now migrants from sub-Saharan Africa and Asia who made money for the smuggling mafias. I’d passed a similar group in Algeria a year earlier, dumped the night before on a plateau, 100km from the nearest town.

The famous ‘swimming’ figures in the cave at Wadi Sora are nothing special compared to the wonders in Karkur Talh, but the cove scooped into the south-facing escarpment of the Gilf made a great place to camp. It was Christmas Eve and from my suitcase I pulled out a pyramid of Ferrero Rocher chocolates to pass among the desert ambassadors settled around the fire.

Before I’d left the UK I’d been given a mysterious waypoint, said to be for an intriguing and at that time secret new rock art site discovered nearby, just a year earlier. Not knowing quite what to expect, we were amazed at what we found when we located the point: an overhanging shelter 30 feet wide covered in layers of rock paintings and engravings, both mundane and obscure, and all like nothing I’d seen before. We sat back in amazement, snapping away, again and again finding new detail and connections. Mysterious headless creatures shared the wall with handprints, rows of dancing figures and long-vanished beasts. Said to be the most significant rock art discovery in the Sahara in 40 years, it shows that the Sahara has many secrets to give up yet.

We were now heading around the west side of the Gilf, at times creeping over the Libyan border on to easier terrain, not that there was anyone there to stop us. Without the plateau’s protection, the north winds blew down on us and chilled the day, and next morning Mahmoud’s Land Rover was so groggy it needed a good session with the gas stove under the sump before being towed reluctantly into life.

We curved back east towards the edge of the Gilf and found ourselves on a trail of camel bones: the old raiding route from Kufra in Libya to Dakhla (via Abu Ballas, see above). By mid-afternoon the plateau receded and before us the pale dunes emerged: the final run through the Great Sand Sea to Siwa which, even with the now lightened cars, would be the most difficult part of the route.

We came upon a group of cairns marking an entry point to a northbound corridor which led to the so-called Libyan Desert Glass Field, discovered in the 1930s by one of Bagnold’s chums. At the time the origin of the pale green LDG (above) was still a mystery: the result of melted sand following an extra-terrestrial impact, or a more prosaic flint-like concretion of sediments? Kevin had his ideas as we strolled around the gravel corridor like beachcombers, unearthing fragments of glass. Even though no evidence of an actual crater has been found, since out visit shocked quartz has been detected in the bedrock of the LDG field. This supports the theory that it was indeed formed by a meteor impact some 28.5 million years ago, rather than an atmospheric airburst (passing airborne meteor) which can also melt the surface rocks. Similar green glass is found in heat-fused sand at nuclear bomb test sites.

Some bits had even been carved into Neolithic tools, and a few years ago it transpired that an emerald-like gem in a piece of Tutankamun’s jewellery (left) was in fact LDG, suggesting the pharaohs (or people they traded with) roamed further west of the Nile than was originally thought.

We left the glass field, with 500km of dune driving ahead of us. The Great Sand Sea is composed of dunes that run in parallel lines for hundreds of kilometres from the Siwa Depression to the Gilf Kebir in the south. But the further north you go the more confused the dunes become; the easy corridors close up so that by the time you near Siwa the dunes are in a complex, non-linear jumble that makes progress very slow and dangerous, even with our greatly reduced payloads.

I’ve never been a fan of dune driving and was not looking forward to this section; besides the dangers, dune driving is hard on the cars and your nerves, and is not even that interesting. Although it’s exhilarating when you get it right, because of the need to maintain speeds or sink, it’s only a matter of time before you blow it.

It was my turn to be in Mahmoud’s car that morning and I wasn’t thrilled by the prospect. Over the previous few days, either the flexing body or the need to really slam the doors shut had cracked the windscreen which was now held together with stick-on shading. Then, when the back passenger door I was leaning on flew open as Mahmoud executed one of his signature swerving manoeuvres, I decided enough was enough – I would rather take my chances being brained by the oil drums in Loutfi’s Toyota than put up with Mahmoud’s erratic driving.

By the end of the day the gravel corridors closed up and filled with sand and we began to tackle the dune banks to reach the adjacent corridor leading north. We were all secretly pleased when Mahmoud decided against pushing on for the direct route to Siwa and instead chose to skirt around the less severe formations to the west, along the Libyan border. Even then, the cars regularly sank into unseen soft patches. We ended the day close to the Libyan border, knowing that tomorrow there was no choice and we’d have to head northeast, back into the Sand Sea, to reach Siwa.

A heavy dew covered us all the following morning, a sign that we were in the more humid Mediterranean climatic zone. The dune lines kept pushing us away as the drivers scanned for a low pass to make a hop to the east. At one point Mahmoud was on the very crest of a drop when a harsh gear change popped a half shaft – not surprising with a 3.5-litre bus engine turning the original Rover axle. In fact, it turned out to be only a stripped hub drive flange and was easily changed while we warmed ourselves in the sands over a quick brew.

With drive restored Tobe got into position to film the cars coming down the slope. Loutfi rolled down in the red Tojo then Mahmoud eased over the crest, but for some daft reason eased to the left where a slight hump pushed up the wheels and slowly tipped the top-heavy Land Rover on its side with a thump and a clatter.

For a few seconds the upside down engine turned over, sucking sand through the snorkel and oil into the cylinders. A few moments later it stalled and Mahmoud emerged from the capsized wagon unhurt and flopped down in the sand in shock, followed by Aisa and Faraq the mechanic. Luckily Mahmoud had had a cargo barrier fitted which had stopped gas bottles and the like bouncing off their heads, but the roof rack’s contents spilled down the side of the dune.

While these were collected, Ibrahim brought the white Rover down the dune with no drama and a rope was run from the fallen car to the powerful Tojo. The conspicuous silence from the crew made it clear that they too thought that Mahmoud had been an accident waiting to happen, though as it turned out it was his pride which received the biggest dent. Excuses that the parabolics sprang back and pushed him over were diplomatically dealt with as the car was dragged down the slope and pulled back onto its wheels (see video below). Faraq set about ejecting the oil from the cylinders and removed the sand-caked air filter which could be cleaned later. Just an hour after the tumble the Mahmoudmobile started with a puff of black smoke and settled down to a steady tickover.

Chastened by his experience, we continued cautiously northeast, now recce-ing possible passes on foot and easing gently down the slip faces, knowing that it wasn’t over until it was over. Limestone pavements protruded from the dunes and bits of vegetation popped up here and there. At one point we discovered some fulgarites (sand petrified by lightning into a glassy helix tube) as big as an arm. Our homesick crew could smell Siwa and were keen to press on, not least Ibrahim whose wife was expecting their seventh child any day. But by dusk we did the right thing and stopped a couple of hours out of Siwa on a chalky outcrop studded with fossilised sea-shells.

By mid-morning next day we’d worked our way through the dune maze and were looking down on the inky blue lake which led to Siwa, feeling like we’d finally come ashore from a long sea voyage. On his home turf now, Ibrahim led the way through the dunes to the hot spring of Bir Wahed (above) where were scrubbed off a fortnight of Saharan grime and ordered a string of Oranginas and crisps as if they were the very fruits of Eden.

Pingback: Old Land Rover ~ Algerian Sahara – 2008 | Sahara Overland

Pingback: Mountain of Goats | Sahara Overland

Pingback: Sahara – West to East Crossings | Sahara Overland

Pingback: ‘O’ is for Old Sahara Maps | Sahara Overland

Pingback: Sahara – The Empty Quarter – Overlanders' Handbook

Pingback: Uweinat •Gilf • Great Sand Sea 2000 | Sahara Overland