For centuries camels were the way to go in the Sahara. Introduced from Arabia around 0AD, they proved to be ideally adapted to transporting heavy loads without needing water (providing they was daily herbage or straw). A couple of centuries ago huge caravans numbering thousands of camels would transport salt, slaces or sold from the souks of the Sahel.

Today, camelling is still a satisfying way to travel in the desert. You don’t ride; the camels carry all the provisions. But besides the obvious motos, 4x4s and aircraft, here are some other ways people have chosen to cross the great Sahara.

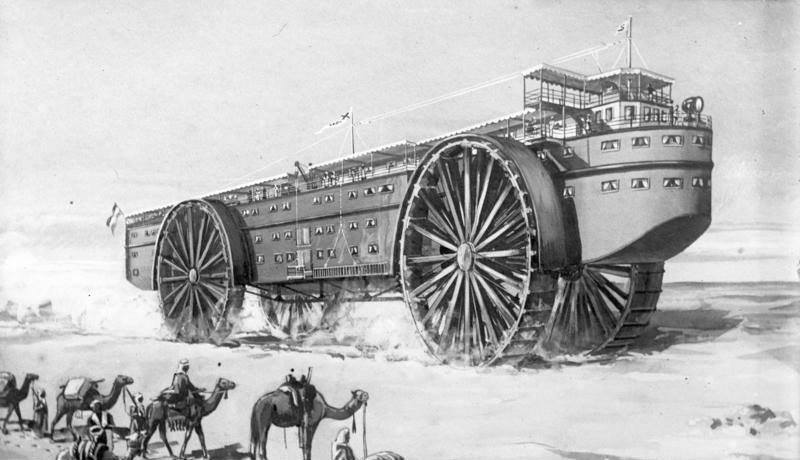

Steam Powered Landship

In the Edwardian era of luxurious, steam powered ocean liners, why not a desert liner to tame the vast sand oceans of Sahara? Like something from a Jules Verne novel, giant traction wheels would glide over the sands while desert tribesmen looked on in awe.

This one never got beyond the drawing board, but today massively overloaded gros porteurs (left) from the pre-electronic 1980s diesel apogee still grind across the desert sands.

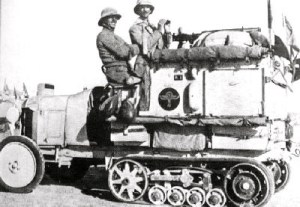

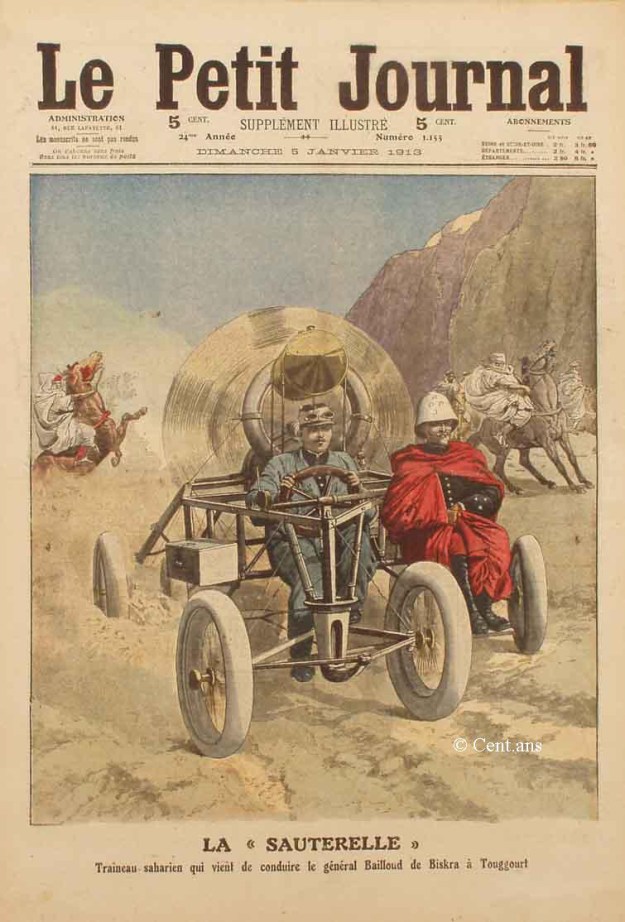

Sauterelle Propeller Car

With the advent of the gasoline-powered motorised cart, or ‘car’ for short, traction in the desert sand was the problem with early, low-powered and inefficient engines.

Those new fangled flying machines never this issue, so how hard can it be to combine the two? Behold the wingless, deafening wonder known as the Sauterelle propeller car of 1912 which could literally put the wind up you. Nicknamed the ‘mobile guillotine’ (not really ;-) it was tested near Ouargla and never heard of again. Read more here.

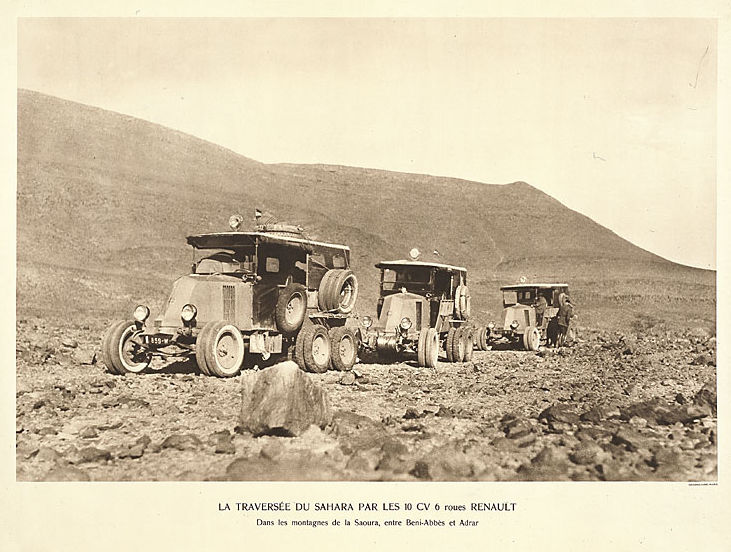

Citroen Half Tracks & Renault Type MH ‘Douze-Pneus’

Motor cars were catching on but traction in the desert remained a problem. During WW1 the Brits under Pat Clayton adapted ultra light, 2WD Model T Fords for the Light Car Patrols in Egypt (left). Desert adventurer Ralph Bagnold used these Fords to travel deep into the hitherto unexplored Libyan Desert.

Around this time Citroen were the first to cross the great desert via the largely flat but very long Tanezrouft Piste in a vehicle fitted with ‘autochenille’ or Kegresse half=tracks (below).

Very slow but not as noisy or deadly as la Sauterelle, they crawled across the desert and were used by Prince Kemal el Din (left) to ‘discover’ the lost plateau of the Gilf Kebir in southwestern Egypt.

Competitor Renault’s solution to the traction problem was the 6×4 10CV Type MH featuring doubled wheels rubber and twin rear axles. Nicknamed ‘le douze pneus‘ (not really ;-), Renault trounced Citroen’s trans Sahara expedition of 1922 with a full, 23,000-mile trans Africa in 1925, the first cars to cross the continent.

Sand Yachts

You got wind, you got sand, so why not Sand Yacht across the Sahara to Mauritania?

Full story.

Chinese Wind Barrow

Regular family cars like Morris Oxfords were now commonly used to cross the Sahara (sometimes ending in tragedy), so lorry manufacturers among others, undertook costly, promotional but essentially pointless Sahara west to east expeditions.

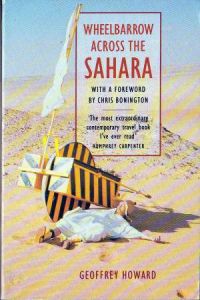

People were running out of stunts to stage in the Sahara until 1974 when priest Geoffrey Howard came up with a new angle that sounded like a lost sketch from Monty Python.

Lately back from volunteering in Nigeria with his wife, he had a Chinese sailing wheelbarrow built, then set off to cross the Sahara ‘unaided’ from Beni Abbes to Kano, raising money for the poor while also positing a new means for locals to transport their goods (not unlike the initial motivation of the 1980s Africar project).

As one reviewer observes: ‘That he was assisted by two British soldiers … in a Land Rover and accompanied him most of the way makes it sound easier – but this was a safety consideration, and he made his own complex rules about how and when they could assist.’

National mountaineering treasure Chris Bonington contributed a harsh foreword: ‘Not much of an adventure’ I thought, ‘pushing this ridiculous wheelbarrow along a well travelled road or track with a [support] Land Rover in constant attendance.’ You’d hope that line is followed by ‘… but Howard’s monumental endeavour changed the face of human powered adventuring…” or some such.

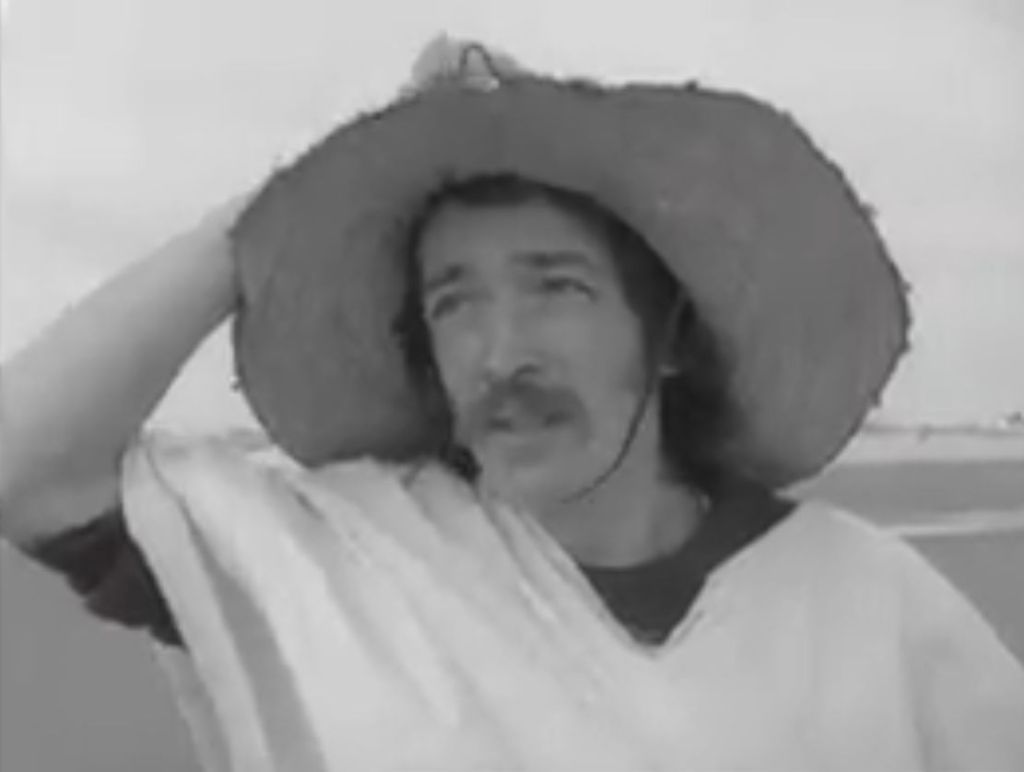

I can’t recall, but do remember similar conclusions to CB on reading the book decades ago: a silly stunt that turned into an endurance test. The sail idea soon proved useless so he had to resort to pushing the barrow for the three-month, 2000-mile crossing in his flapping get up.

There’s some grainy archive film on the BBC of a lightly mocking Bob Wellings (remember him?) interviewing Rev. Howard training on Morecombe Sands in full costume. He ends with ‘I have no fears whatsoever’ The 1990 book is easily found online, new or used.

Three wheel- 2WD FatBike

A regular bicycle will struggle on the piste to carry more than a couple of days of water. One answer: Jean Naud’s 2WD, three-wheeled fatbike replicating the multi-tyred Renaults of yore.

And like a modern lorry, to reduce the pedalling effort, one axle on Naud’s contraption could be lifted and disengaged (left) when payloads dropped or the terrain allowed. It worked too, he crossed the Sahara twice on fat bikes.

Read more.

Microlight

In 1988 prolific adventure travel writer Christina Dodwell teamed up with experienced microlight pilot David Young (recently back from a close shave in Nepal) to fly 7000 miles in a Pagasus XL from Cameroon to the Atlantic in what was still the pioneering era of microlighting.

I knew of it but never read this one; it’s not a trans-Sahara, more of a Sahel traverse via the Aïr mountains and Timbuktu. From the back cover map it looks like they followed roads and main tracks for navigation, maybe due to range and landing issues. Luckily they didn’t do an Icarus and all ended well in Dakar four months later. There’s a book of course (right), one of Dodwell’s many which is widely available online.

Rollerblading with tricycle sail cart

With the 21st century bringing a choice of no less than three asphalt roads spanning the Sahara at 1500-mile intervals, it was time for the rollerblade (or ‘inline skate’) and the humble push-cart sail-tricycle to have their day in the sun. It’s what rollerblades and bitumen were made for.

Five thousand clicks from Spain to Dakar, watch Mark Heuss’ cool short film below.

Did I miss any other batty trans Sahara crossings?