See also

Sahara Tours 2026

Even before I turned to camel trekking, one of my favourite Sahara books was a translation of Philippe Diole’s 1956 The Most Beautiful Desert of All (reviewed; aka: Sahara Adventure in the US).

Philippe Diolé was an adventurer, author and best known was for his many diving books written in the infancy of scuba (Self Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus) which had been invented by his later friend and associate, Jaques Cousteau. It’s said he was a regular crew member on Cousteau’s boat, the Calypso.

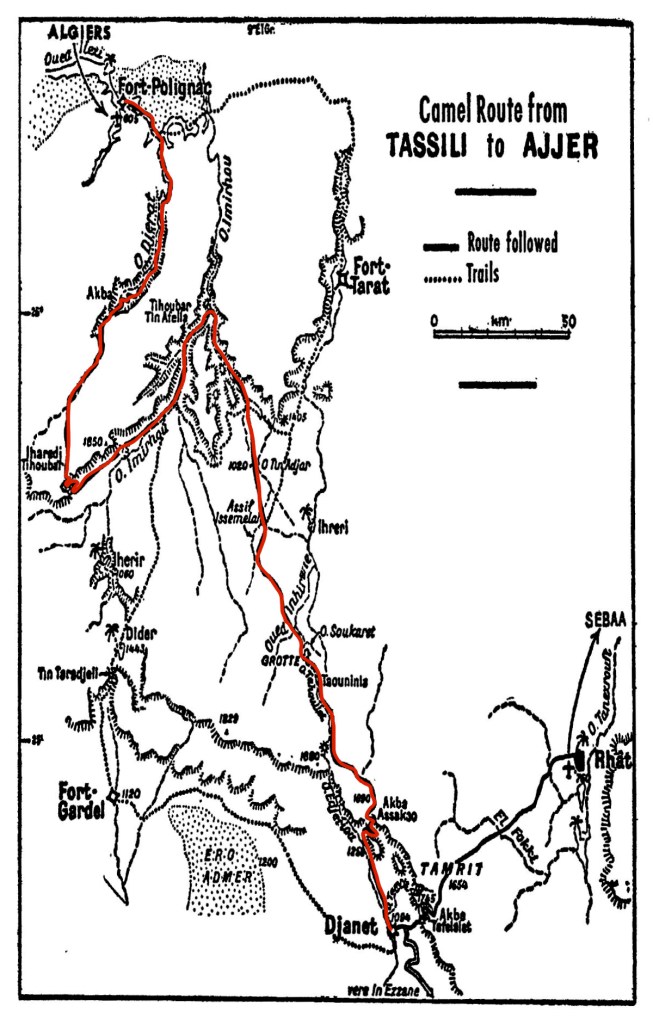

around 1953 he flew down to Fort Polignac (today’s Illizi on the north edge of the Fadnoun plateau) and set off on a month-long camel trek down the Oued Djerat. In the 1930s I believe this was the first location in southern in Algeria where French administrators and others like E F Gautier and Henri Lhote became fully aware of the extent, variety and quality of prehistoric rock art which went on to be to be found right across the Tassili n Ajjer plateau, and continues to be found to this day.

With his unnamed, scrawny Tuareg guide and cook boy, Ali, the continued south to the Tihoubar track and followed what is now a road northeast to Imirhou, before turning south again across the bare plateau towards the Akba Assakao leading down the Tassili’s southern rim and into Djanet. he had been told by the Commandant Imbard at Fort Polignac of a rock shelter painted with fine scenes which he’d seen over a decade earlier.

… I am determined not to leave the locality without finding that cave. Commandant Imbart remembered having seen there a fish painted on the rock.

A few days from Djanet near Wadi Tahouilet, Diolé’s guide finally locates a rock shelter painted with fish and giraffes.

The guide has run on ahead of me into the cleft, and now bursts out of it again, with a glad cry: “Sardinal Sordinal” (To a Targui today, practically the only fish in existence are those that come in cans.). This fish, however, bears no resemblance to a sardine. It is enormous, and it is painted in a beautiful shade of dark violet. From head to tail it measures twenty-three inches. A good catch! On the back, a little behind the head, two horns are plainly visible. Beside this creature is painted a figure whose feet and arms appear to be branches covered with leaves. Even its sex is shadowed over, and its head is crowned with branches.

This prehistoric grotto measures ten and a half feet in depth by eighteen in length. A bulky pendant block divides the ceiling into two separate domes. The walls are almost entirely covered with paintings, which differ in subject, style, and colour. Human silhouettes, dogs, oxen, wild sheep, scenes of the hunt and of war follow one another across these rock surfaces. Especially noteworthy are two admirable giraffes with speckled coats. In prehistoric times the giraffe was probably the ideal game animal of the Sahara: not very wild, visible from a distance, harmless, prolific [and] living in herds…

Attracted, as many of us are to places off the beaten track and obscure historic routes, I’ve long thought it might be fun to try and retrace either Diolé’s route across the plateau to Djanet or to visit the Cave of the Fishes. But even when reading the book years ago, I had a feeling this was already a little-used trail. It’s doubtful anyone’s been that way for decades. Most tours now sweep across the much more accessible and even more impressive rock art sites close to Djanet at Tamrit, Sefar and Jabbaren.

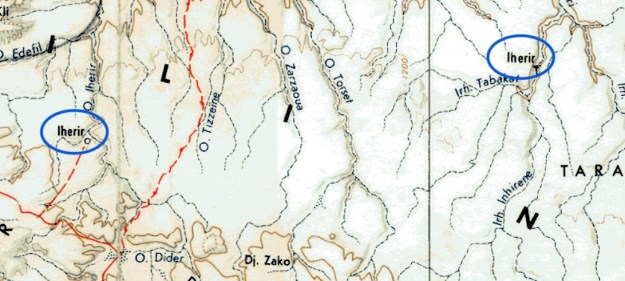

It’s a well-worn Saharan cliché, but Diolé’s route also passed close to a genuine ‘lost oasis’ that I’ve also been curious about: Ihreri is some 80km NNW of Djanet and often mistaken with the much more visited Iherir now easily accessible off the Fadnoun road. Sacre Bleu, even the 1967 IGN 1:1m map (above) mistook the similar names and printed a second ‘Iherir’ in the east. Local guides actually call it Inhirene, like the oued on which it is situated.

Tucked down in its small canyon, Ihreri may well resemble the similar, semi abandoned oasis we came across on an Amguid Crater trek in 2010 (above), set in a region prolific with Stone Age megalithic tombs. The grassy patches as well as the sudden density and rustle of date palms were an unexpected sight after a week out in the open desert with nothing bar a thorny acacia for shade.

I’m also sure I watched a (German?) documentary in the mid-1980s about some tourists reaching a very remote oasis in the Tassili and getting a hostile reception. For some reason I think this may have been Ihreri, occupied by the grumpy vestiges of its date-cultivating denizens. Inaccessible by car, now it’s possible the only visitors come seasonally with camels to maintain or harvest the palms.

On and off I’ve tried to get the Diolé plan off the ground, being told among other things it was too hard or there was very little herbage on the plateau that year. But recently I made contact with an Algerian agency that seems keen to try something out of their well-trodden comfort zone. Perhaps the easy ‘fly-in’ work is getting a bit repetitive these days. Venturing off the well-worn tram rails and into the unknown has its risks – uncertain herbage for the animals as wellas vital water sources for all. But by first proposing a recce to establish a longer trek’s viability, in 2026 we hope to be visiting the Cave of the Fishes and the Lost Oasis of Ihreri.