See also

Trans-Sahara from Uganda – 1954

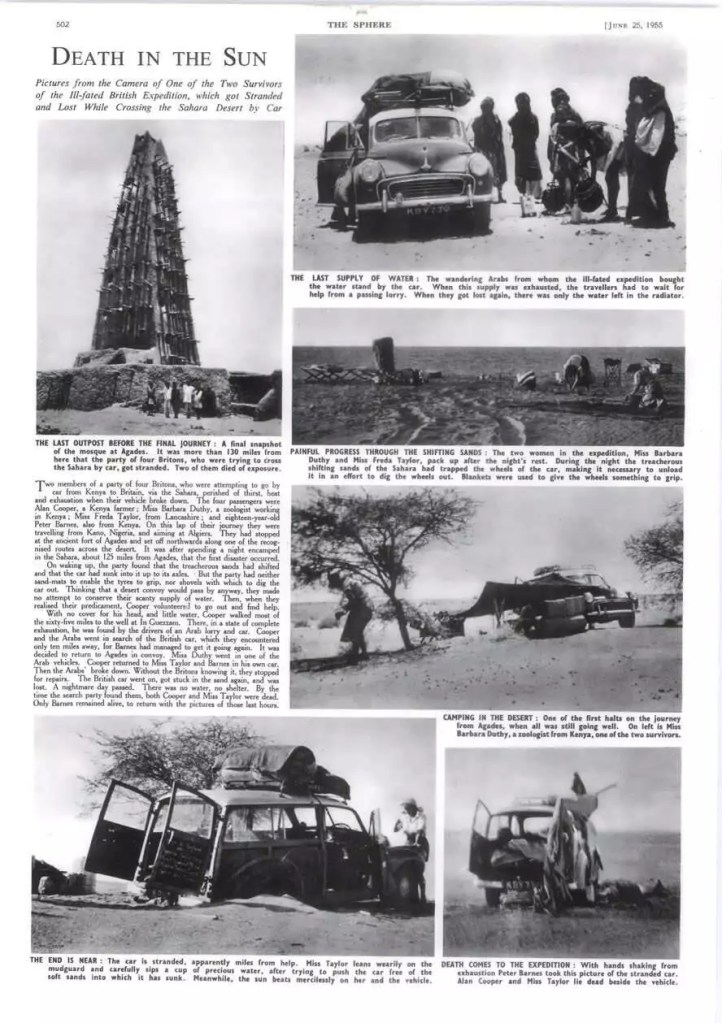

Shell Guide to the Sahara (1955)

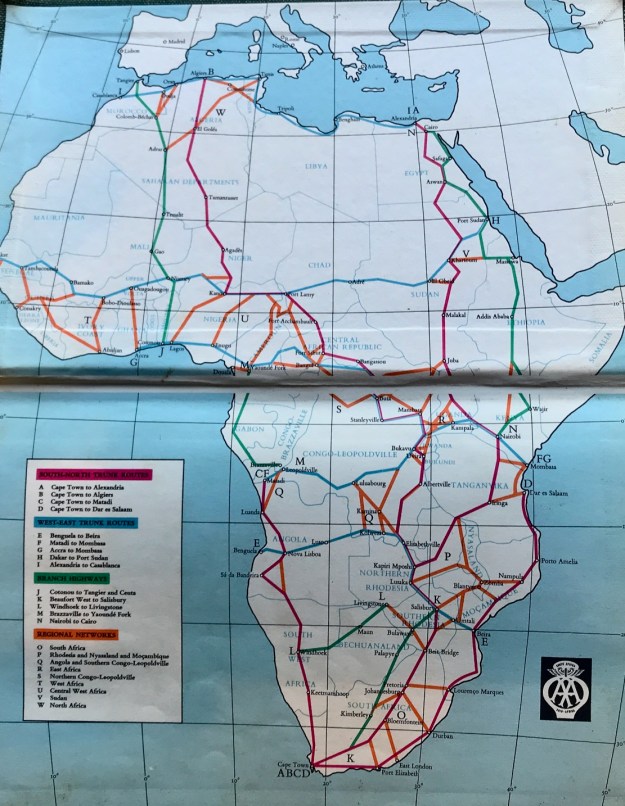

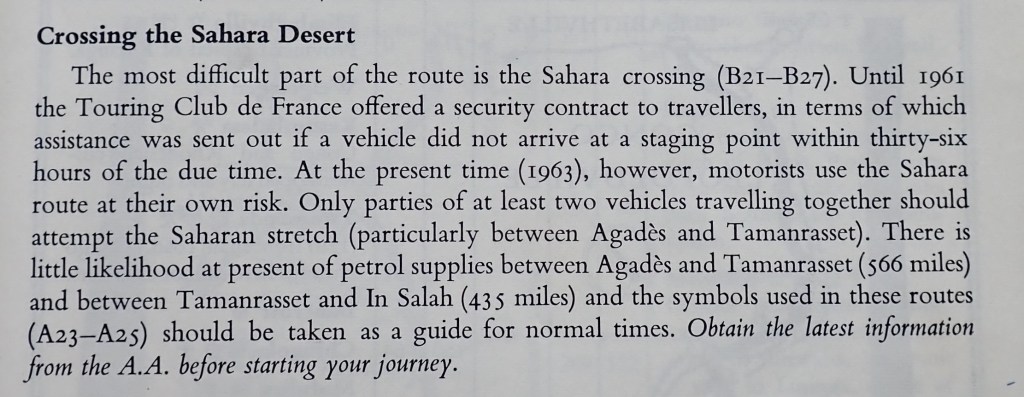

Trans Africa Routes (1963)

I was working at London’s Travellers’ Bookshop when Trek came out in 1991 and of course, I gobbled up the desert drama, painstakingly researched by Paul Stewart (better known for the Edge Chronicles young adult book series).

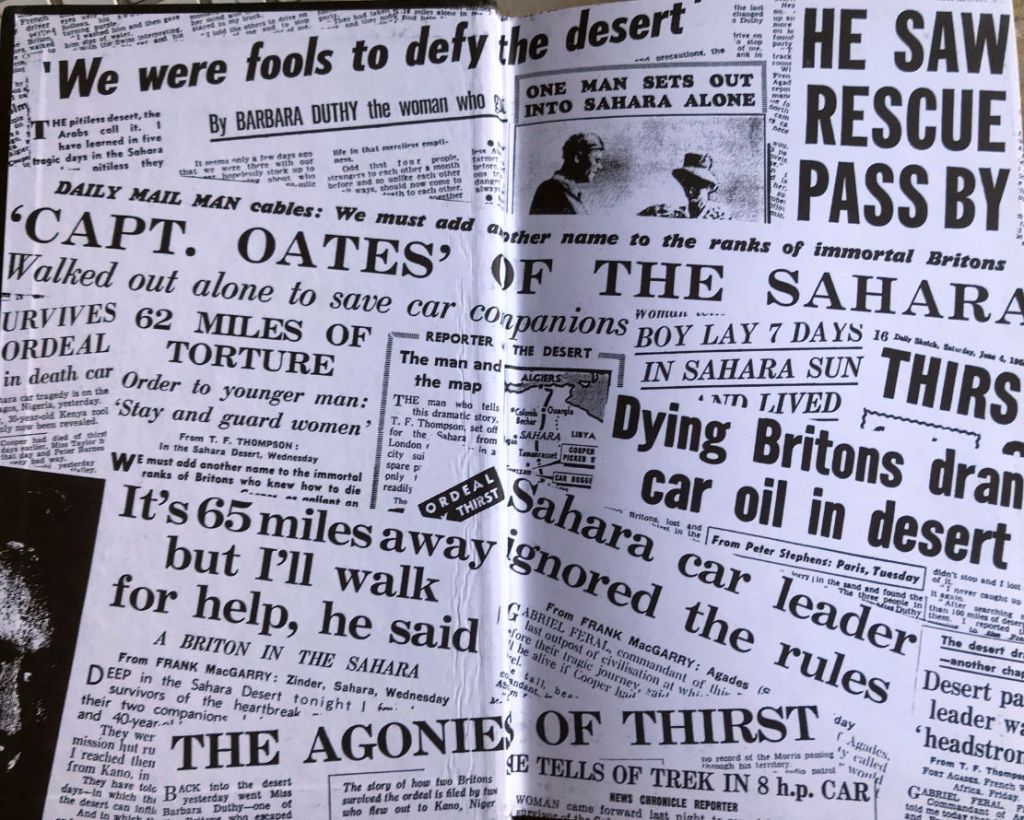

The book came about after Stewart had the story recounted one of the expedition’s survivor’s at her Kenyan guesthouse in the 1980s. He soon realised it was a headline on a June 1955 ‘day of your birth’ newspaper reprint he’d been gifted decades later. Stewart was born on the day the sensationalised events broke across the UK press (see bottom of the page).

Recently writing up the similar Danish story which took place a year earlier in 1954, I realised I’d never reviewed Trek, so recently blitzed through it recently. Only this time I had a slightly more knowledgeable eye, having evolved into a Sahara and overland know-all in the intervening decades.

Trek tells the story of an ex-pat foursome who, in April 1955, set off in a near-new Morris Traveller (like above) to drive from Kenya via the Congo and the Sahara back to the UK. They were led by Alan Cooper, a self-confident but irresponsible bon viveur who’d farmed, ran hotels or led safaris, all with little success (forthright bio from his old school). Perpetually short of money, he wanted to visit his ageing mother back in the UK and perhaps kick-off another business scheme. Back then driving overland was the cheapest option. To cover the trip’s costs he advertised places at £175 a seat in a local paper, but on the day delivered much less than promised: a single small, inadequately prepared car, far less any hired locals to undertake the chores.

The three passengers were 17-year-old Peter Barnes, despatched by his mother to man him up (and whose detailed diary was a gold mine for the author years later), a genteel spinster Freda Taylor who’d erased 17 years off her true age of 55, was captivated by the idea of the Sahara, and was caught in Cooper’s spell. Barbara Duthy was a more independent-minded woman, a scientist and pilot, who from the start challenged Cooper’s incompetence and cavalier practices. It was the ageing Barbara whom the author met in Kenya in the 1980s.

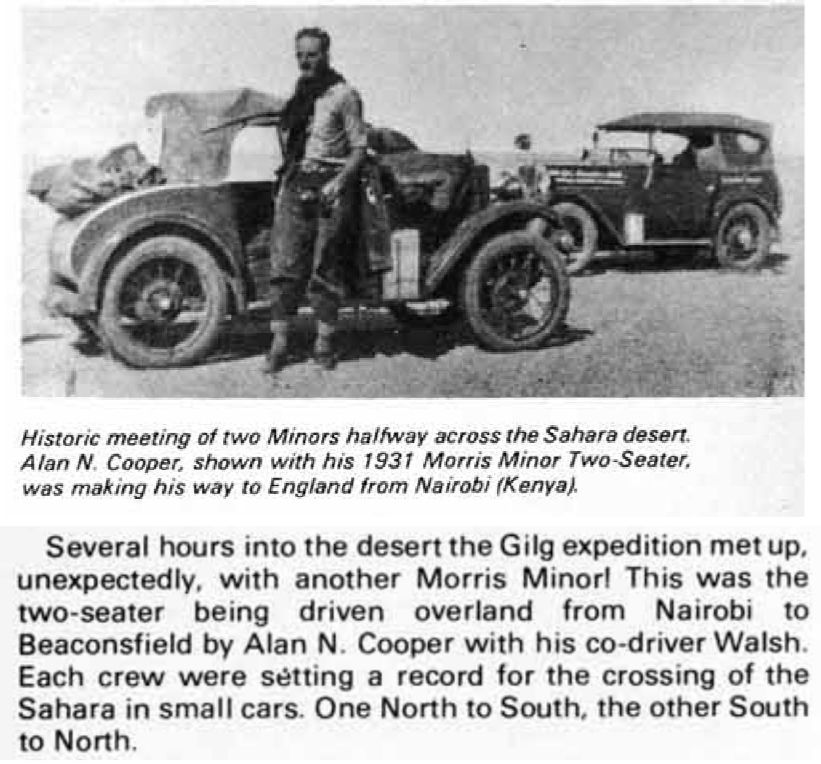

To his credit, over 20 years earlier Alan Cooper had completed a similar African crossing in a two-seater Morris Minor, even getting this achievement featured in The Times as the smallest car to cross the Sahara to date.

The original Minor was more Model T Ford than the rounded post-war ‘Moggie’ we know and love. By 1961 that famous model became the first British car to sell a million, and was my parent’s first car (left).

On that first crossing the young Cooper had just one passenger via the Tanezrouft crossing from Gao to Colomb Bechar in March, the time of year when temperatures in the Sahara begin to escalate quickly.

Near Reggane he ran into two other Brits and a desert guide in a bigger Morris car heading south for the Cape (pix below; 1978 documentary on YT). Both Morris crossings occurred barely a decade after Citroen half-tracks had been the very first ‘cars’ to cross the Sahara north to south, pioneering the long, bleak, waterless but flat Tanezrouft route to Mali and the Niger river. On the way they established the famous ‘Bidon’ staging posts which were to feature on future maps. In the 1930s I don’t think the Hoggar route between Agadez and Tamanrasset was yet regarded as motorable.

The ‘8hp’ question

In Trek a highly unlikely ‘8hp’ gets attributed to Cooper’s 1950’s Traveller. It’s hard to think how, other than the author spotted it in a 1955 newspaper headline (below) and thought nothing of it. These days a suped-up moped could make 8hp, but throughout Trek ‘8hp’ gets much repeated to underline the Traveller’s crushing unsuitability for the task it had set itself.

Was there ever a mass-produced, post-war car that made just 8hp? Actually there was, (thank you internet): the ultra-basic 1949, 375cc 2CV put out 9hp, was much ridiculed at the time and soon became the butt of ‘does it come with a can opener’ jokes. As Frenchman Cyril Ribas has proved over many decades, a 2CV does actually make an effective desert car.

A bit more interneting soon reveals even Cooper’s 1931 side-valve Minor pushed out a healthy 19hp while weighing less than 600kg. His near-new, 800-cc, engined Traveller clocked in at 28hp. A two-litre Series 1 Landrover of the day made 55hp, so 28 was about right, and far from a puny 8hp.

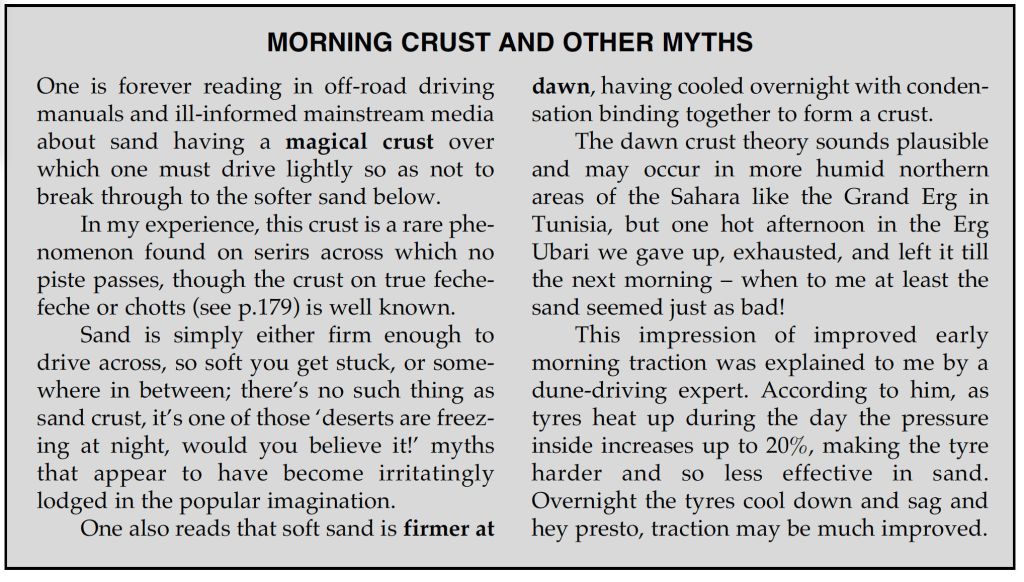

Oh M G, Paul Stewart does not get cars! Like most people, nor is he a desert driver. Irksomely, along with other tenuous suppositions and repeated myths (like wandering dunes making tracks unrecognisable within days) he goes on repeatedly about the perils of breaking through the thin ‘sand crust’ which formed each night under the star-lit desert. Don’t start me on sand crust (see below).

I admit all this will go over most readers’ heads because they will find Trek an engaging read of how one person’s behaviour can lead to an all too predictable disaster. One thing the author does well is paint a vivid picture of colonial Africa at that time, and why so many Europeans chose to live there, enjoying a standard of living they’d never have back home. In the mid-Fifties that era of privilege was coming to an end as demands for independence spread across the continent – not least from Kenya’s Mau Mau insurgency. As you’d expect, Peter Barnes’ diary recorded little interaction with locals, either Africans or colonial administrators, so the author cooks up period dialogue to help jazz up the tale. Sometimes it passes unnoticed, at other times it jars. It’s a bit different from an author lightly embellishing their own memoirs or travelogue with their own voice.

The Travelling foursome left Nairobi in mid-April, almost exactly a year after the Danes and, in my opinion, an usually late departure if intent on tackling the Sahara a month later. Unlike the Danes, Cooper was far more casual if not outright reckless in his planning and preparation, sparing little room for vital provisions, spares and equipment to fill his paying seats. Under pressure to reach Agadez before French authorities suspended desert crossings from mid-May to November, the group averaged up to 200 miles a day across equatorial and Sahelian tracks. As a result, four weeks later, both passengers and car arrived at the desert’s southern edge, weary and exhausted.

Like the Danes’ near-new Morris Oxford, Cooper’s 6000-mile-old Traveller needed new big end bearings. Except in his case the cause was, bizarrely, not stopping after smashing the sump on a rock in Cameroon (the Danes carried a spare sump for this very reason). The Traveller’s oil drained away and inevitable engine damage occurred. Limping on to Kano in then British Nigeria, the wrong spares eventually got flown in so a proper repair was bodged to save more waiting. Heading north for Agadez, the engine was soon knocking again.

The French requirement of a £1000 bond to cover a desert rescue described in the Danish article did seem unusually high. In Trek, a more plausible refundable £50 per person is mentioned to cover a search, should a vehicle be overdue at the next checkpoint. With new bearings fitted in Agadez, but just a week before the desert closed for months, Cooper tricked his group by claiming they’d been given the all-clear to leave but they had to go right now. In truth he knew he’d never have got official approval to cross the desert. Along with the imminent closure, it was this deceit which may have forced Cooper to push on into the desert, when turning back would have been wiser. Because of his actions, no official departure record was logged and so no rescue mission was launched until news of the lost Morris reached Agadez, a week so so later.

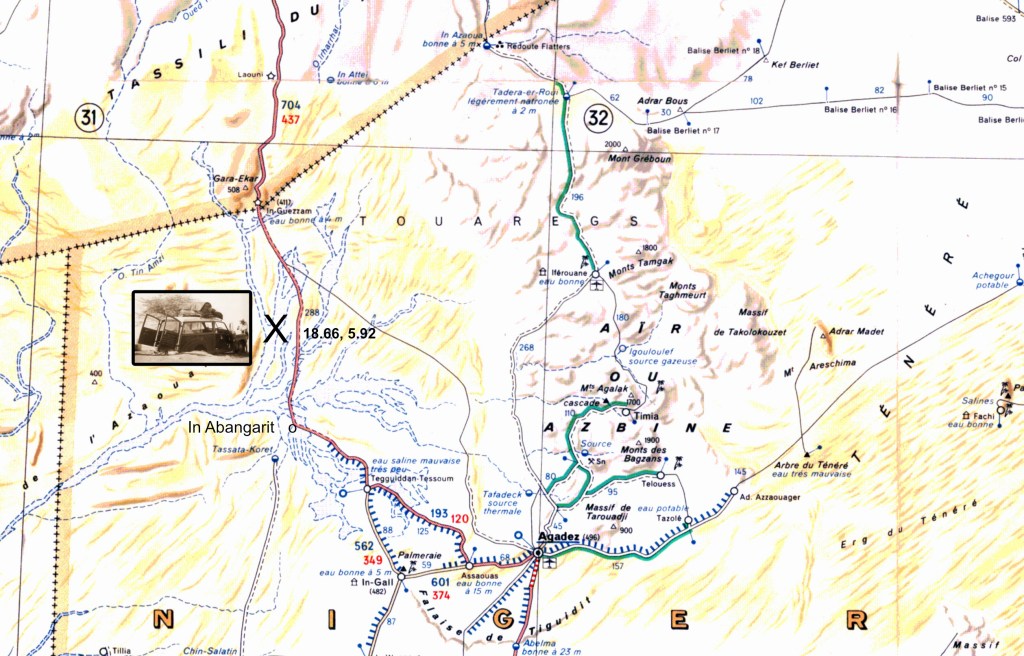

In the 1950s the piste from Agadez to Tamanrasset went west past the salines of Tegguidam Tessoum before turning north at In Abangarit well for In Guezzam on the Algerian border. This was long known as a sandy route, tougher but shorter than the original Tanezrouft across Mali and Algeria. When the uranium mine opened in Arlit, north of Agadez, in 1971, the primary crossing switched to that route over less sandy, or at least more travelled terrain.

The 1990 edition of the Sahara Handbook (left) claimed ‘4×4 vehicles are not necessary’ on the In Abangarit piste (right). The Swiss Beetle (see below) proved that and the book’s original authors undertook most of their travels in a Kombi van. But the Handbook went on to advise, from Assamaka ‘… head south on a bearing of 170°. Keep speed up… Several big sandy patches and seas of bull dust, especially [110km] south of In Guezzam‘.

There was no Assamaka back in the 1950s, but by the 1980s the Handbook warned ‘Niger frontier officials [at Assamaka] have been known to force … travellers to go via Arlit… [to Agadez]. Subsequent landmarks given on the now little-used In Abangarit route description are spaced up to 100 or 150km apart, with balises as every 5km, too far to see one from the next. In 1986 on the the shorter Arlit piste I myself soon lost track of the balises, but that’s another story (below).

In the enervating, pre-monsoonal heat, the foursome did manage to stagger across the desert to within 50km of In Guezzam. But getting that far had entailed a lot of digging and pushing, decimating their inadequate water reserves. It was at this point the Traveller caught up with a lorry rescuing the nearly dead Cooper, who 50km earlier had set off north on foot from the then bogged car to get help. The other three got the car moving again and caught up.

Cooper was found delirious by the southbound Algerian driver in a resupply truck (a Citroen Type 32 perhaps) carrying masses of water and recovery gear, and accompanied by a Swiss couple in a VW Beetle. Much against Cooper’s demands, the group insisted on carrying on south to Agadez to get Cooper urgent medical attention. Once in Agadez, the lack of permission would have come to light and they’d all miss the desert crossing window for sure. A compromise was agreed: they’d backtrack together about 150km to the well at In Abangarit where the Traveller would wait to join the returning Citroen heading back to Tam. To reduce weight in the Morris, Barbara chose to ride in the truck – a decision which probably saved her life.

Peter ends up driving the Morris at the front of the convoy, while Freda tended to the semi-conscious Cooper in the back. But on losing sight of the following vehicles, at the still domineering Cooper’s insistence, fatally, they kept going. This rashness is hard to explain other than a bloody-minded craving to control events, no matter the risks. The Morris strayed off track, as is so easily done, got badly bogged again and, with all the water in the truck, first the severely dehydrated Cooper and the frail Freda died by the car. These deaths were almost certainly hastened by the colonial-era outfits shown in photographs: baggy shorts, short sleeves and frequently no headwear which all accelerate the body’s water transpiration in an effort to keep cool. It’s why Tuaregs are covered head to toe. With just hours to live, Peter was found a day or two later by a search party of Legionnaires sent from Agadez.

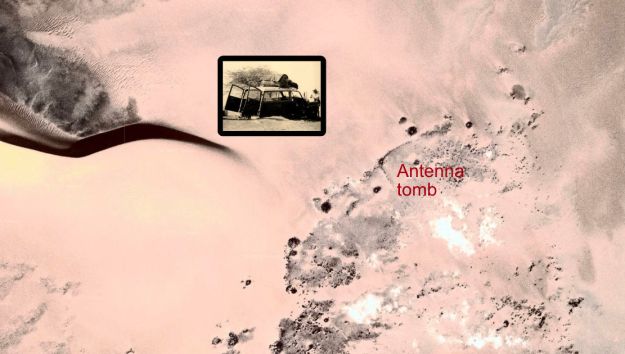

Cooper and Freya were buried by the Legionnaires at a waypoint given in the book as 5.55’N x 18.40’W. Even once corrected to N5° 55′ W18° 40′, this is way out in the Atlantic, some 600km off the coast of Guinea. I suppose in 1991 verifying a waypoint was less easy than now, but wasn’t anyone in production even curious? Jumble it about some more and you get N18° 40′ E5° 55′ which looks about right: a point among low dunes 10km west of the current piste and halfway between In Abangarit and In Guezzam (see map above). The book makes a lot of the doomed expedition’s ill omens; perhaps the final one is that the car came to rest just half a mile from from a cluster of pre-Islamic tombs, including a classic, east-facing antenna (above).

Cracking yarns of abject overlanding folly like Trek have all helped entrench the Sahara’s mystique and notoriety, and the British papers of the Fifties had a field day: ‘drinking engine oil…’, ‘Oates of the Sahara…’ with some even inventing foul play to explain the deaths. You can buy Trek for a few pounds. What a great movie it would make.