This book is free online as are other Sahara books

Year’s ago I owned a prized copy of Francis Rodd’s, The People of the Veil (now free online) documenting his travels and studies among the Aïr Tuareg in 1922-3. Not sure I ever actually read it cover to cover, but it remains one of the most detailed ethnographic studies of the Aïr- or southern Tuareg in English. Herni Duverier had written Les Touareg du Nord sixty years earlier while travelling in Algeria’s Hoggar and Ajjer regions. And a decade or more before that, the indefatigable Heinrich Barth had travelled south from Ghat, over the Tenere, down through the Aïr, all the way to Timbuktu then back the long way via Bilma, before dying in Berlin, aged just 44.

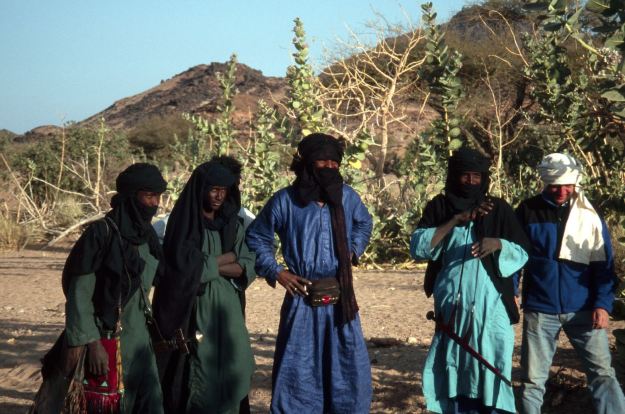

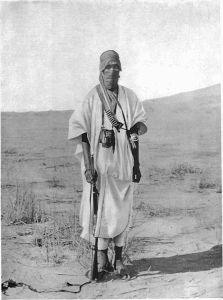

I’ve travelled twice through the Aïr (2001, 2006) and both times was struck by how much more ‘picture book’ the Tuareg of the Aïr were (below), compared to those in Algeria. Even if they were playing up for us tourists, it all helped fulfil one of the best Saharan circuits you could do at that time.

Born in Kirkwall, Orkney, aged 20 Angus Buchanan (1886-1954; bio) emigrated to Canada where he briefly ran a construction business before serving in the East Africa Campaign during WW1. By now with a keen interest in natural history, in 1919 he travelled by camel from Kano as far as Iferouane, later writing up Exploration of Aïr: Out of the World, North of Nigeria (right).

Rodd was a Mayfair-born aristocrat, colonial administrator, diplomat and banker, and invited himself on Buchanan’s second, 1922-3 expedition to the Aïr.

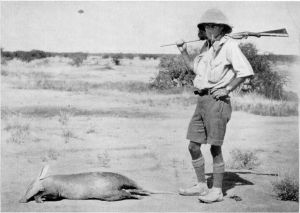

Again with the support of the British Museum and 2nd Baron Rothschild (a keen zoologist), Buchanan was tasked with amassing animal specimens.

Perhaps because he covered it all in Out of the World, Sahara is not a chronological travelogue, but covers diverse vignettes such as caravan life, camp fires, raiders and so on. One chapter is a rather cheesy first ‘person’ biography of Buchanan’s beloved camel, which promptly died soon after they parted ways, 14 months later, and to whom he dedicated the book.

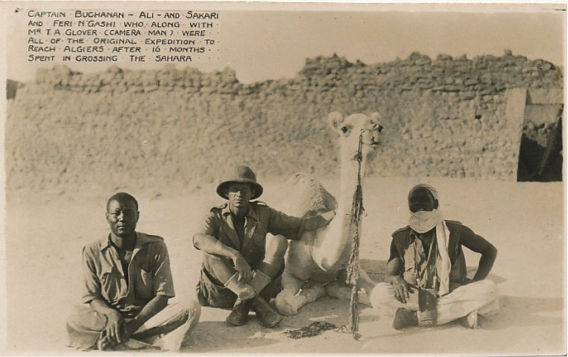

Rodd returned from the Aïr after nine months, while cameraman T. A. Glover completed the whole 3500-mile trek to northern Algeria with Buchanan. But beyond this brief credit up front: “My companions were: Francis Rodd… and the cinematographer… T. A. Glover” – these two pass entirely unmentioned in the text, bar at the very end for Glover. Rodd does not even get a picture.

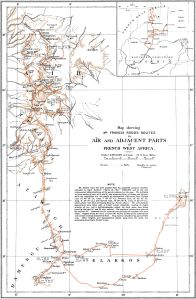

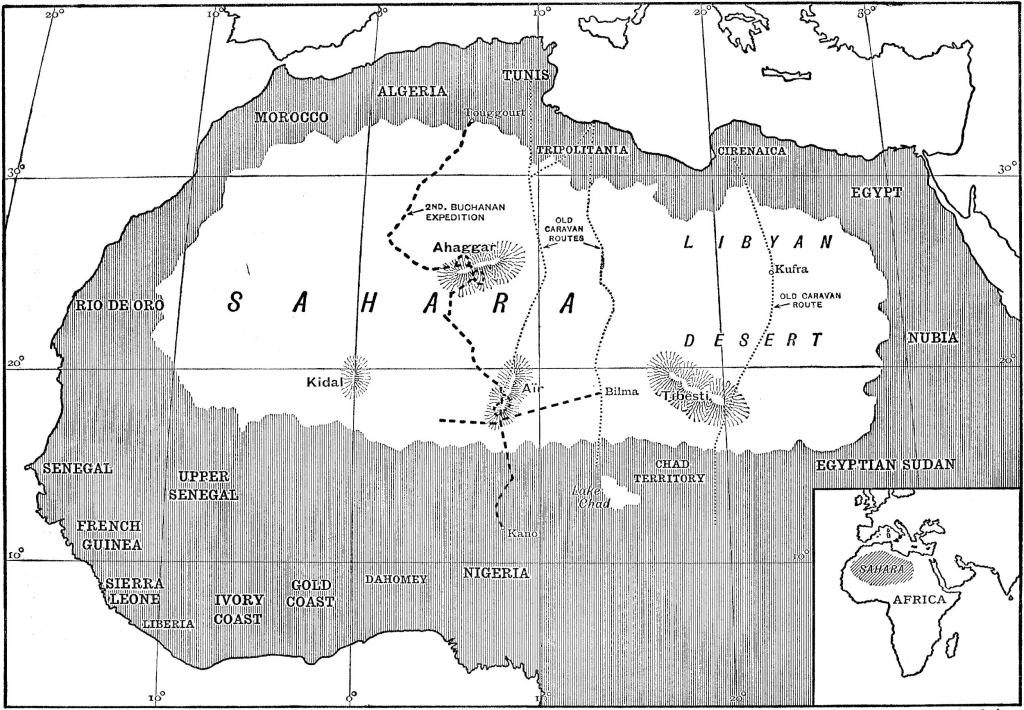

They must have shared many experiences, and in Rodd’s book (his route, left) Buchanan is mentioned over two dozen times. Perhaps they went their separate ways once in the mountains? Or perhaps they did not get on, as so often happens in the Sahara.

Or, lacking a family crest, ancestral pile and Eton & Oxford education, could the class gulf have been too great for the self-made Buchanan? The rather tortuous paragraph below from the preface of his earlier book hints at an insecurity about his ‘uneducated’ status as a gallant explorer. But like the similarly ‘low-born’ René Caillié, their achievements in advancing our knowledge of the Sahara speak for themselves.

It might be said that the traveller [himself] was a rude man, for he was untutored in the deep studies of the scholar of many languages, as in a measure might be expected and understood of one whose occupation called him from day to day to don rough clothing and shoulder a rifle and march outside the frontiers of civilisation.

In his earlier book, he described the Tuareg as ‘the strangest race I have ever come in contact with independent, haughty, daring, unscrupulous, and lazy in leisure, yet fit to rank among the finest travellers and camel-riders in the world.’

And in Sahara, the chapter titled The People of the Veil (like Rodd’s book), he elaborates on the aloof, mysterious and warlike nomads:

… they who are pre-eminently a class unto themselves, and they who are responsible for much of the romance that has given to the Sahara a world-wide mystical fame.

He’s not the first to distinguish their noble demeanour from other desert dwellers, so aligning the Tuareg with what were considered the best ‘white man’s’ values. As you’d expect, some captions and observations show the casual racism of that era, implying the superior character of the ‘almost white‘ Tuareg to those around them – something you rarely see said of an Arab (unless you’re Wilfred Thesiger or T E Lawrence). Battier theories have aligned the chivalrous Tuareg with a lost tribe of Crusaders, often misattributed to the popular Tuareg cross.

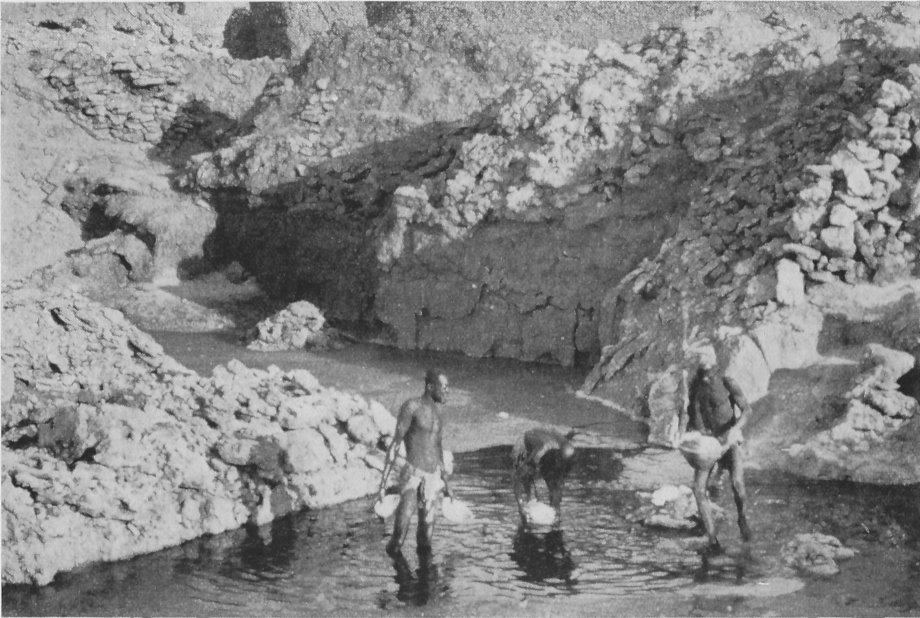

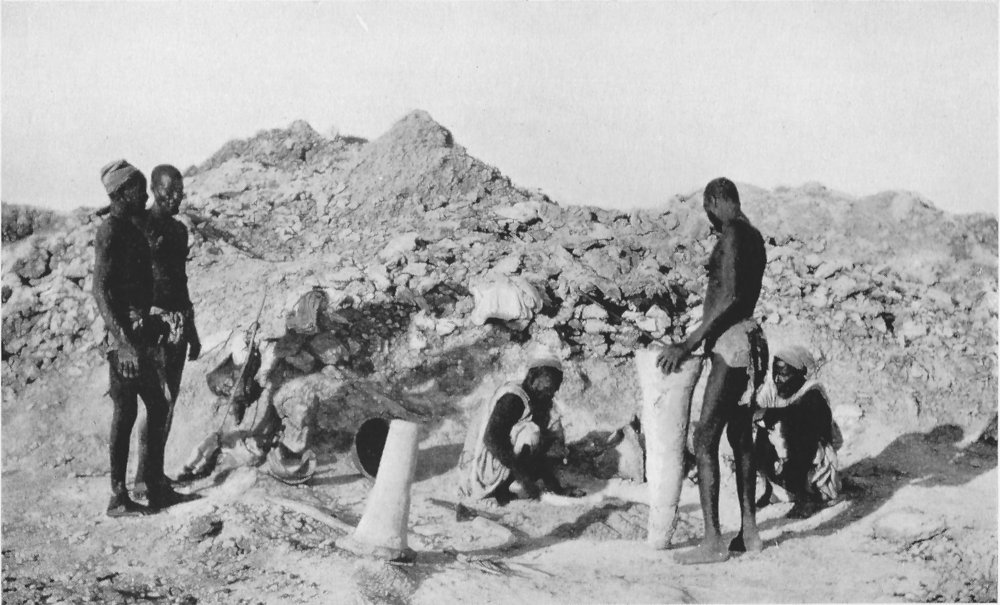

An interesting episode describes joining the ‘Taralum’, better as known the great Tagalem or azalai salt caravan covering 800km from the Aïr foothills east through the dunes to Bilma oasis and back. Though Bilma had been a French outpost since 1906, it’s possible that Buchanan and Glover may have been the first Europeans to undertake, or at least record, the famous forced march leading many thousands of camels to bring back salt cones from the Bilma salt ponds (below).

Along the way Buchanan manages to give a vivid description of the remote oasis of Fachi (‘A City of Shadows’) and its Beri-Beri (or Kanuri; ‘from Kano’) occupants, as well as the ancient origins and commerce of Bilma. These chapters read with a little more vitality, possibly because they cover new territory for Buchanan. A few years later he went on to write a novel, The City of Seven Palms whose title is based on Fachi.

In the style of the era, Buchanan heavily romanticises his travels, the people he meets and the stories he hears. A chapter called The Hand of Doom recounts what sounds like a tragic Tuareg legend about a chief who doggedly pursues bandits who’d abducted his wife Kahena, ‘the belle of the tribe‘, only for them to die in the desert once reunited. It bears a resemblance with the novel, L’Atlantide, also from that era

The narration of this tale slips into a goofy, proto-Shakespearian prose, but fear of raiders was still a very real menace in the 1920s, whether ‘Arabs’ from Ghat, Tubu from the east, or just other Tuareg clans on the prowl. In fact right into the 2000s and the advent of jihadist ransom kidnappings, bandits would occasionally rob tourist groups and agency cars in the eastern Aïr, while other parts of the Sahara remained relatively safe.

Sahara draws to a close with a listing for no less than 207 birds and 64 mammals, some unknown to western science. The expedition’s primary mission was to shoot and collect these animals for museums back in the UK, and Buchanan was bitterly disappointed that he missed the chance to shoot the last lion of the Aïr. It had been speared while harassing villagers near Timia. Meanwhile… Giraffe was seen only once, he adds, but on a number of occasions their fresh tracks were crossed. These were left unfollowed, as a specimen of the species was not wanted.

Along with many places names, another odd omission were pre-islamic tombs and prehistoric artefacts and rock art (below) which Buchanan must have come across, and Rodd records in his account. There’s no mention of either in his earlier book, either.

Though also not mentioned, research elsewhere reveals that the French had only a few years earlier forcibly cleared out the Aïr’s Tuareg clans, which was how many ended up in northern Nigeria. As a result, Buchanan frequently describes an impoverished land of rude dwellings and destitute, starving people. Indeed, the sand-surrounded oases were almost as appallingly barren as the desert around them, except for their groves of dates, which bore no fruit at that season of the year.

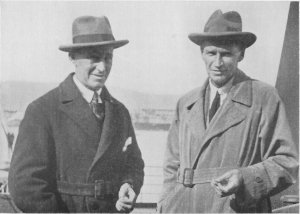

Another disappointment was that no description was given of the final crossing from the Air into the Hoggar and across Algeria. The striking image above was found somewhere online, and the basic map does indicate a couple of exploratory circuits in the Hoggar before swinging out west into Adrar Ahnet on the way to In Salah and Ouargla for the rail head at Touggourt (below). Here the camels were unburdened of their vast trove of specimens, and the two Brits (left) – presumably deeply exhausted after well over a year on the trail – continued with their loyal manservants Ali and Sakari to the UK. As mentioned, his steadfast camel soon died, as had most of the 35 camels who left Agadez, as well as two of the crew.

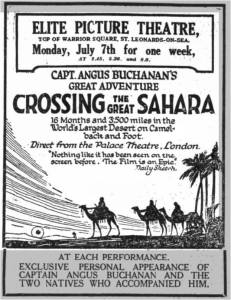

Back in England the press ran with the adventure and a film, ‘Crossing the Great Sahara‘, was soon produced. All four (and possibly some camels) went on to become part of a travelling roadshow in the UK and Europe. Left, a girl posses with Ali and Sakari and a camel at a screening of the film in Southampton.

The film is archived at the BFI, but while not viewable online, you can easily walk into the BFI’s Mediatheque viewing library on London’s Southbank and search for it the database. It’s the oldest Sahara film listed, but unfortunately only the first couple of reels survived or got digitised. In 20 minutes all you see is the grand departure from Liverpool, some British dignitaries in Nigeria then various Hausa and Fulani bush folk performing for the camera. What there is is well shot; what a shame the rest is missing and we never get to see the Aïr. It must have been a huge effort to shoot it all. One interesting caption was an observation along the lines of ‘Was this where Blues originated?’, presumably in response to hearing African music. I know that connection was widely repeated once World Music came on the scene in the 1990s, but did not know it went that far back.

In fact, so popular was Crossing the Great Sahara that in the same year a spoof, Crossing the Great Sagrada, was also released, decades before Monty Python or ‘Ewan and Thingy‘ got in on the act. We watched that too at the Mediatheque. It’s a bit silly.

All in all, I ended up wondering if Buchanan’s account of his first foray of the Aïr may have been a better read, thrilled as he would have been by the novel experience, even though it ended with a debilitating fever.

Rodd too was clearly deeply influenced by his shorter spell in the Aïr. His gravestone in Presteigne cemetery (above) features the Tuareg cross of Agadez, as well as the enigmatic Tifinar epigram embossed on the cover of his book (below) which Rodd translated as ‘Naught but Good’.