Part of the occasional Sahara A to Z series

Hang around long enough and you’ll get the full set

An MCN feature I contributed to about hot weather riding.

You can buy MCN digitally here.

An MCN feature I contributed to about hot weather riding.

You can buy MCN digitally here.

A 2008 BMW 650X was my 2014 project bike

Go to most embassies and at the very least you’ll find a few tourist pamphlets and a poster of a couple frolicking by a fountain. There was no such noncing about at the Libyan Interests Section in London’s Harley Street in the late 1990s. Down in the grubby basement mean-looking guys ground another fag into a Brit passport and ignored you purposefully. Tourist literature was limited to a defiant newsletter commemorating the ‘drawing of the Line of Death’ against imperial aggressors. Charming. Just the spot to enjoy a spring break on a bike.

‘Visa?’ I asked meekly. ‘Hello? Visa?’

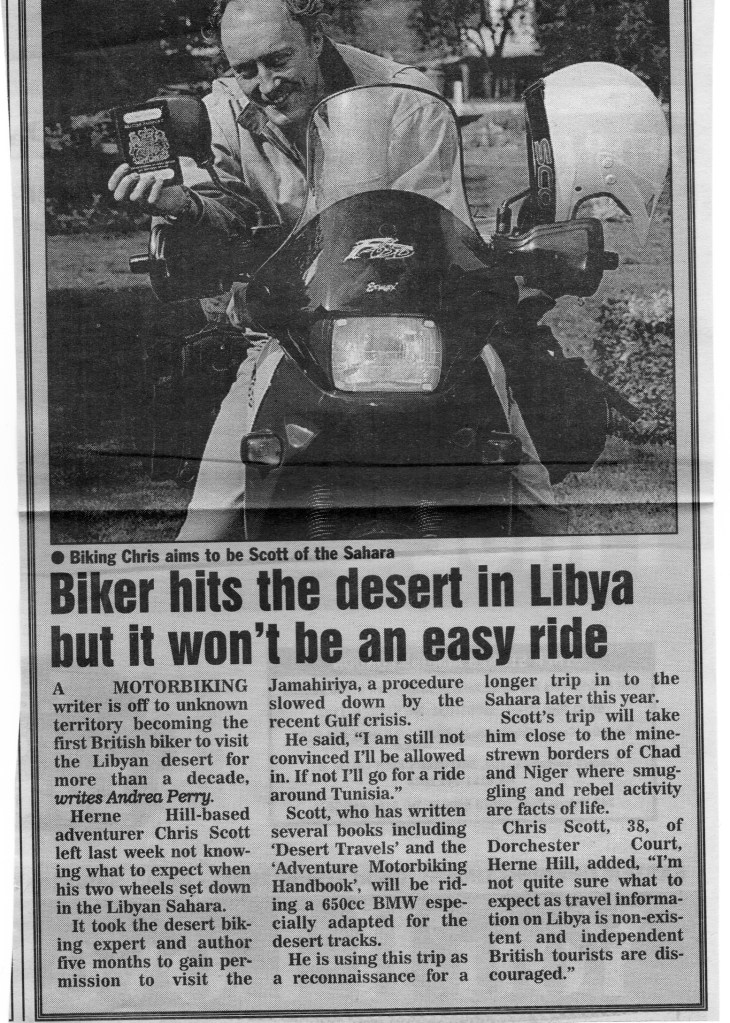

It has taken me months to get to this point. In November 1997 with the third edition of AMH completed, I decided it was time to practice what I preached. Libya sounded interesting and BMW’s Funduro trailie would make a change from another Yamaha XT600Z Ténéré.

Buying a three-year-old F650 (bike #47) was easy; getting a Libyan visa involved countless dead-end faxes to various Libyan tourist agencies for the required invitation. Eventually, a mysterious internet connection provided an invite at a price and my permit was telexed from Tripoli in early April. A week later I was walking down Harley Street with the requisite stamp. There was no going back now.

I may have been nervous about my destination but I was less uncertain about the bike. I’d always fancied trying the Funduro. They came out in 1993, a trusty combination of Rotax engine and BMW build quality plus a naff name and a look unlike anything else. No one had anything bad to say about them other than being a bit heavy for off-roading. The revvy engine took a bit of getting used to after my torquey XTs, but with the right tyres I was sure the 650 would be up for some piste bashing.

As I was hard-up modifications were kept to a minimum – or that’s the excuse I give myself. Truth is the bike should need the bare minimum of adaptions.

A fat Michelin Desert was squeezed on the back after a bit of sawing at the outer knobs. The front end took a ‘rear’ 19” Pirelli MT21 with a lot more knob-chopping and fitting a mudguard off a Honda VT500. Road riding on these tyres was initially unnerving, especially the ‘marbles-on-glass’ MT, but I soon got used to it.

The bike had come with a new o-ring chain, some brand I’d never heard of, but I figured it would last the trip. The 27-litre Acerbis tank managed to look barely bigger than the original but promised a useful 500km range. To help work out distances in kilometres, BMW UK gave me a metric speedo which saved on possible errors when converting from miles to kms. A chunky alloy Touratech GPS bar mount held my snazzy new Garmin 12 firmly in place, and a cheapo ball compass was screwed on the dashboard. Lastly, I fitted an in-line fuel filter, a cig’ lighter plug for the GPS, fork gaiters and a high screen. It was March now, high time to head south.

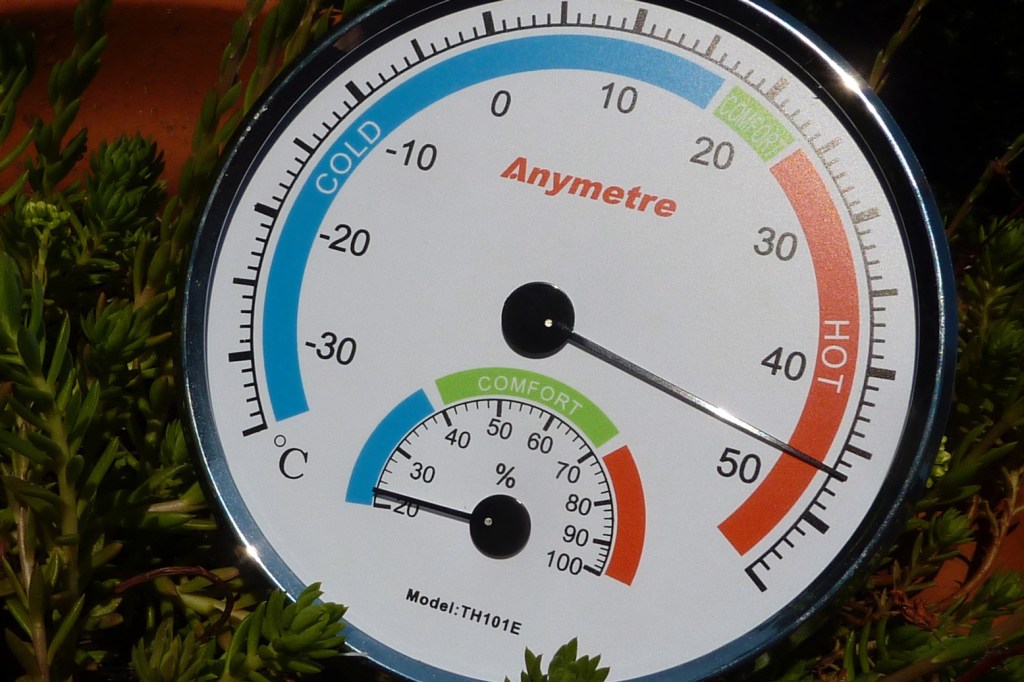

To save my knobs I took the overnight Motorail from Paris to Marseille and then caught a ferry to Tunis where ensued five hours of messing around from one counter to the next. If this was Tunisian immigration what would Libya be like? And another thing troubled me: had I left it too late in the season? By now temperatures were climbing steeply right across the Sahara and with it, expected water consumption and a host of other problems.

A couple of months earlier a New Year’s meet up with a guy who worked in the Libyan oil fields actually put me off the whole idea. He warned me about the enervating ghibli winds which blew in April and melted strong men’s brains. A story of a guy who’d driven out into the storm sounded especially grim.

‘About a month after the guy had gone missing a nomad came into the camp and asked if we wanted to know where our Toyota was? We said yes and it cost us. Then he asked did we want our body back – it cost us some more. Turns out the guy had just parked up with the engine running and walked out into the sandstorm.’

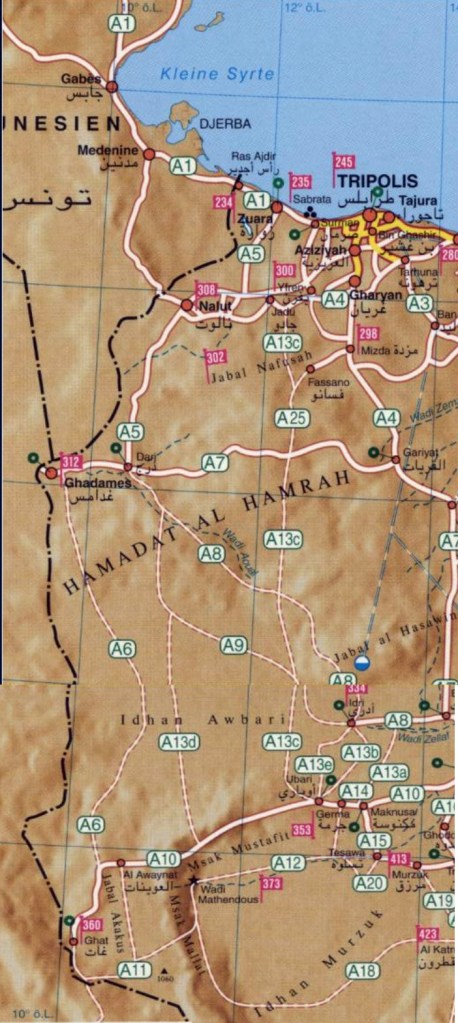

With a weather eye out for the ghibli, by the next afternoon I was close to the Libyan border with a wodge of illicitly bought Libyan currency stuffed down my crotch. At the border I was again resigned to hours of shuffling from one hangar to the next, filling out forms and getting stamps. But by chance one of the many Libyan travel agents I’d given up on recognised me and whisked me through the formalities in just twenty minutes (and only a hundred quid!). Stunned at my good fortune, I set off towards Tripoli in the fading light and soon pulled over to fill the tank up for just 60p. That’s right: sixty pence. Super petrol works out at 2.5p a litre, or if I you’re feeling stingy, regular costs just 2p.

Dozens of the roadside wrecks traffic along Libya’s main coastal highway testified to the lethal mixture of ‘get-out-of-my-way’ gangsters in blacked-out Mercs and lopsided farmyard bangers piloted by granddad in coke-bottle specs. So after a night in the bushes, I was relieved to turn off the Death Highway south towards Ghadames, 550km away. Now the roadsides were only marked by posters of the Brother Leader, hands raised in a ‘we’re all in this together!’ salute.

As I rode into the desert on super smooth blacktop I wondered when the real heat would begin. I didn’t have to wait long. By mid-afternoon the temperature had risen to the high thirties and out of the blue the bike started spluttering. Surely I haven’t got through the tank already, I thought? Undoing the cap revealed plenty of gas. The bike started up but a few miles later cut out again. I got off, had a look at things and guessed the cause. A combination of half empty tank and minimal throttle at cruising speed added to the afternoon heat saw the trickling petrol evaporate in the added fuel filter and cause vapour lock – cutting off the fuel supply. Stopping cooled things down and got the petrol flowing again. Later on, when pouring cooling water over the filter body I saw the petrol level rise instantly, I knew I’d guessed right.

Knowing the problem was as good as solving it, so I filled up first chance and carried on to Ghadames, arriving zonked out at the empty campsite just as the sun set. Slumped out on the sand, I had a think. If it was reaching nearly 40°C this far north, how hot would it be further south? The vapour lock was easily fixed with a cardboard heat shield (above), but I was keen to get the BM on the dirt. Was I taking too great a risk riding alone? From here my plan was to ride across the Hamada el Hamra, or Red Plateau, then cut over the edge of the Ubari Sand Sea down to the Akakus mountains near the Algeria/Niger border, altogether about a week’s riding.

My French guidebook (all that was available) claimed the route across the plateau was a straightforward 450km gravel track with a well half way. Just about within my fuel range, though in these temperatures water consumption was another matter. I checked over the bike, wrote myself a road book and planned to leave early next morning.

That night at 2am a rising gale woke me and I dozed fitfully as the tent wobbled and the palms flapped overhead. Dawn revealed an orange sky and a thick dusty haze. Was this the ghibli I’d been warned of? I postponed my departure, hoping it would die down, but in the end set off back to the village of Derj where the plateau track began. I’d reassess once I got there.

Topping up at Derj junction, I was on the verge of heading back to Tunisia. As I sat there mulling over ‘dare I’ with ‘should I’, the attendant leaned out the door and said

‘Eh, la mangeria?’

La what? ‘Mangeria!’ He made the universal mime for chow.

‘Ah oui, merci.’

In the desert I find I automatically slip into French, but unlike Morocco, Algeria, Niger, Mali and so on, Libya had actually been an Italian colony – and even then, only briefly. That’s presumably where this slang for food had come from. As I ate my bowl of oily stew a little German Isuzu pulled in and, as always in the desert, we sized each other up. A brief chat revealed that Rainer and Katja were also heading across the Red Plateau and would be happy to have another vehicle along for safety [Katja took most of these pictures from the car with my camera but I’m sorry to say I have not photos of them].

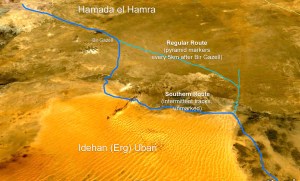

The aptly named the Red Plateau, a barren, undulating prairie of rust-coloured gravel cut by dry water courses. Rising to 800m, my oilfield mate hadn’t much good to say about it: a pitiless void that was either freezing or baking and criss-crossed with enough tracks to confuse even the wily nomads.

Enjoying the security of another vehicle, it felt great to be on the dirt at last. By myself I’d have been gnawing my lip into a frayed pulp. Shod with uncompromising tyres the BM handled the 40-50kph pace well enough, and it was fun concentrating on the riding instead of sitting on the blacktop. As expected, I was a lot quicker than Rainer’s ex-trans African Isuzu, but I didn’t mind stopping and waiting. Their very presence made this whole excursion much less tense. But there was one thing which bothered me…

‘Rainer, shouldn’t we be at Bir Gazell well by now?’

According to my speedo the landmark should have been close.

‘Bir Gazell? No, that is on the direct route, we are taking the southern route.’ ‘The southern route?’

‘Ya. Here, look. It goes down into the Ubari Sand Sea, turns east and follows the dunes to Idri. My guide book says it’s much more scenic than the boring direct route.’

‘How far is it?’

‘Oh, about six hundred kilometres.’

‘I doubt I’ve got enough fuel to go that far, especially if the piste gets sandy.’

We paused for a moment to consider the implications.

‘Well, I have some spare petrol, about six litres.’ said Rainer whose Isuzu was diesel. We topped up the bike’s tank and decided to take a gamble and press on.

But by late afternoon we’d got ourselves lost. The next GPS waypoint was through the hills to the south, but our track was now heading west towards Algeria, the wrong way. This is all part and parcel of Sahara travel so, not unduly worried, we made camp in a oued and resolved to head directly for the waypoint next morning.

Cross-country riding may sound fun on a trail bike, but in the desert it can be incredibly slow. Once you ride off tracks, however bad they are, you find yourself walking the bike down rocky slopes, blundering up dead-end valleys or edging towards drops. Even with an early start and the bike reconnoitring a way through the hills, it still took us till noon next day to cover the 14km to the waypoint and the route.

Having lost some altitude coming off the plateau, the day began to burn and as I feared, the plateau’s firm gravel turned into plains of soft sand. As all you beach racers know, soft sand has to be attacked standing on the pegs with a nailed throttle and eyes firmly fixed on the way ahead. There is no easy option: back off, the front wheel digs in and you’re off – go too fast and you risk crashing. I did my share of both and finished the day exhausted by more shades of soft sand than the Cote d’Azur.

By now I was already cutting into Rainer and Katja’s water reserves, so we needed to find a well. Their German guidebook identified a source 40km away. We located what seemed the right place and ploughed into the sands where the Isuzu soon mired. While they shovelled I headed over the dunes, riding the sandy banks in all directions just to keep from getting stuck. After a while I found the well – bone dry and full of sand, just like in the movies. This little excursion cost us two hours, a heap of energy and still more water and fuel. We flopped out under some meagre shade. No one said anything.

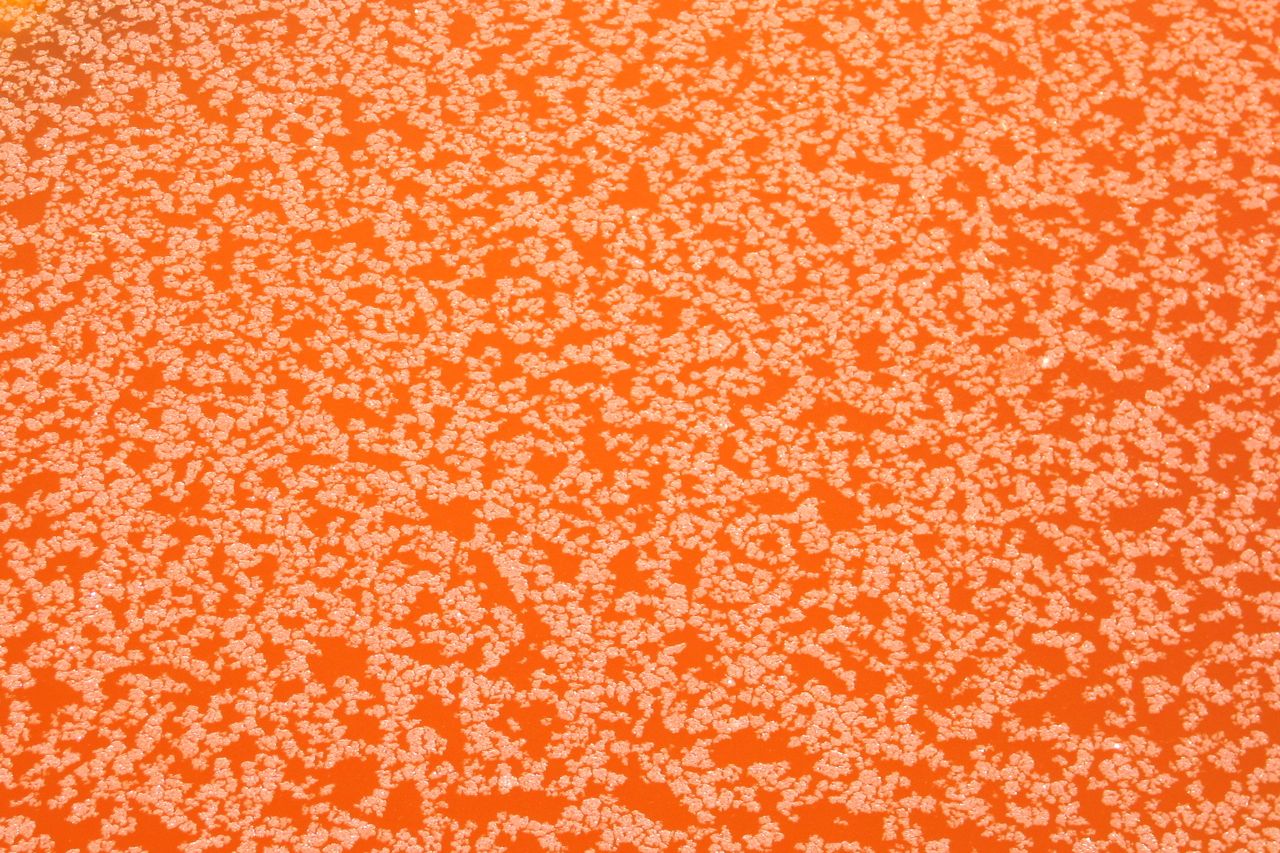

We moved on, at one point encountering the vile surface-crusted powder known as feche-feche. Regular bull dust is often mistakenly called feche-feche; it sounds cool and looks epic in photos but is just fine dust.

This was one of only two occasions I’ve ever encountered it in the Sahara. Often found on the edge of large sand seas, a hard pie-like crust forms and can support a vehicle. Or it might break though into the flour-like blancmange beneath. I spotted it too late, the gnarly tyred Funduro ripped through the crust and sank in, engine screaming in first gear as a 20-foot roost spurted up vertically from the back wheel. By paddling madly I just managed to regain firmer ground in time to grab yet another desperate slug of water.

By now every minor exertion demanded a drink and these exhausting conditions went on for hours. In this sort of terrain the Funduro was just plain old Duro. Sure, the engine was amazingly zippy on the highway, but it lacked the grunt needed to chug through soft sand. And as I’ve found before, the super stiff Michelin Desert might do the trick on a hefty Dakar racer, but even at just 7 psi and with the tyre creeping round the rim (I was trying the self tapers-through-the-rim trick), it didn’t flatten out enough to provide traction. Result: lots of wheelspin and wasted fuel for not much forward progress.

At dusk we located a proper well with a bucket and trough. We filled up everything with water while camels mobbed us for a hand out. Then, fit only to quickly cook up some grub, the three of us crashed out for the third night running. We all knew we’d bitten off a bit more than we could chew, but the end was surely in sight.

We got going early but by nine next morning the bike was halfway down a dune and out of gas. We’d seen no other vehicles since we left the highway at Derj, so there was nothing for it but to lug out twenty litres of water and watch the Isuzu chug off over the sands in search of fuel. With a bit of luck they’d be back tomorrow. I knew that lying still in shade was the best way to limit water loss, so I crawled under a make shift lean-to and waited.

The burning sun inched across the sky and the scorching wind peppered me with sand. Then, just as I began thinking ‘What if…’ a toot-tooting heralded the early return of the little Trooper. An hour or so down the track they’d chanced upon a date plantation where a guy had topped off a jerrican’s worth from his pickup’s oil drum.

I poured the fuel into the tank and we were on the move again, but now the riding became really hard as the track squeezed between the dunes and rocky outcrops. Again we found ourselves searching for wind-erased tracks or taking repeated blasts up boulder-strewn slopes that even the nimble bike couldn’t manage. We covered just 40kms, when the Isuzu got stuck on a dune we’d all had enough and called it a day. Hopefully another early start on firmer, night-cooled sand would finally get us to Idri. The Hamra wasn’t letting us go without a fight.

On the trail by 6am, another four hours saw us finally rolled into Idri, me caked in dust and all absolutely shattered. I felt like I’d done a four-day enduro on a heavy loaded bike in 40-degree temperatures. Hang on, I just did that! A week later I was still aching.

At Idri I bade farewell to the tough German couple and headed north, butt-, leg-, arm-, hand- and back sore after the 600km pummeling. Heavy winds prolonged my retreat and at one point I had the distinctly novel sensation of leaning out round a bend while braced against a 50mph crosswind.

By the Tunisian border that cheap chain was on the way out – and when o-ring chains go they go fast. Back across Tunisia, back across the Med, another Motorail to save the chain and a quick coffee in Paris.

By accelerating very, very carefully I just made it to the Channel, but after only 2000 miles of riding and with the chain adjusted as tight as I dared, 20 miles from London the sprocket turned into a greasy knurled disc. Any thighter and the chain would pull out the countershaft srocket so there was nothing for it but to hire a van to get the bike home.

Years later, on a ferry back from Tunisia, I met Gerhard Gottler, the author of the German guidebook for Libya which Rainer and Katja had used. I explained how we’d struggled on ‘the southern piste’ (route ‘A9’ in his book), the waypoints didn’t join up and neither did the tracks.

“Route A9 is not a piste for beginners.”

On page 350 of Sahara Overland II I wrote a box titled ‘If we’re done for we’re done for and that’s all there is to it‘ about some of the better known plane crashes in the Sahara. Anyone who’s seen the stellar cast at work in original 1965 movie, Flight of the Phoenix (left, not the dreadful 2004 remake) will know what a compelling story the tragedy of a plane crash in the desert can be.

Last week a rather belated article appeared on the BBC where it trended for a day; the tale of how a victim’s relative from the September 1989 UTA 772 plane crash over Niger’s southern Tenere organised the construction of a striking memorial at the crash site to his father and the other 169 who perished.

Less than a year after a similar event over Lockerbie in Scotland, a bomb – said also to have been set by Libyan agents – saw the DC10 break in the sky some 450km east of Agadez, close to the Termit massif. One still of what looks like the cockpit (right) bears a resemblance to the similar well known image from Lockerbie.

Libya’s rather implausible motive was said to have been revenge for France’s support for Chad in the last stages of their border interventions into northern Chad’s Aouzou Strip between 1978 and 1987. This was a little-known Saharan war which had ended when they were roundly defeated first at Wadi Doum near Faya in the Tibesti, and then routed at Maaten al-Sarra, right in Libya itself. However, in July 2011, Gaddafi defectee and former Libyan foreign minister Abdel Rahman Shalgham, told a newspaper ‘The Libyan security services blew up the plane. They believed that opposition leader Mohammed al-Megrief was on board‘.

With part of the £104m compensation gradually handed out by the Gaddafi family, Guillaume Denoix de Saint Marc set about building the huge memorial sculpture close to the crash site. It was completed in 2007 and appears on Google maps today.

The other tale concerns an Avro Avian biplane which crashed in April 1933 between Poste Weygand and Bidon V in Algeria’s Tanezrouft. Featuring biplanes, romance and death in the desert, the story resonates with the popular but very fictional English Patient movie and book. But this tory is all true and a film-making descendant of the loan pilot, Bill Lancaster, is close to completing a documentary about his forebear titled: ‘My Great Uncle; The Lost Aviator‘.

Bill Lancaster was a pioneering British aviator who found fame by flying from London to Darwin in 1927. Despite leaving a family back home, on route he fell for his co-pilot and financial supporter, Australian aviatrix Jessie ‘Chubbie’ Miller (not a nickname you’d think most women would covet).

The adventuresome duo’s romance soon became the Posh & Becks of its day and the couple set up house in Miami. Their relationship then rose to become an outright cause célèbre when, in April 1932 Lancaster was tried for shooting his love rival, Chubbie’s biographer and some say fiancé, Haden Clarke, at their Miami home

Cleared of the charges despite the compelling evidence, Lancaster set off to rebuild his reputation by flying across the Sahara.

While following what may have been the Tanezrouft beacons used by the Citroen motor crossing of 1922-3, his plane went down some 400 kilometres from the Mali border.

After eight days of suffering Bill Lancaster died one year to the day after Clarke’s unsolved murder. His body lay undiscovered by the wreckage of his Avro until 1962 where a recovered diary revealed his agonising last days (‘… the heat of the sun is appalling … my constant craving – WATER‘) as well as his undying love for Chubbie Miller.

The story was fictionalised in 1985 as an Australian mini-series, The Lancaster Miller Affair and again in French in 2009 getting what looks like an exceedingly unsuccessful ‘English Patient’ makeover as Le Dernier Vol (The Last Flight, right) with Marion Cotillard. It sounds like the documentary based on true story may be much more interesting.

More on the Lost Aviator doc here and here and more pictures here.

In March 2006 an eclipse sliced right across the Sahara, from Ghana to the Libyan-Egyptian border on the Med. On its way it passed close to the extinct volcano of Waw Namus in central Libya and it was clear that everyone and his camel would be heading there. Sure enough the place turned into an Eclipse Babylon where tours ops from around the world sought to capitalise on a unique event.

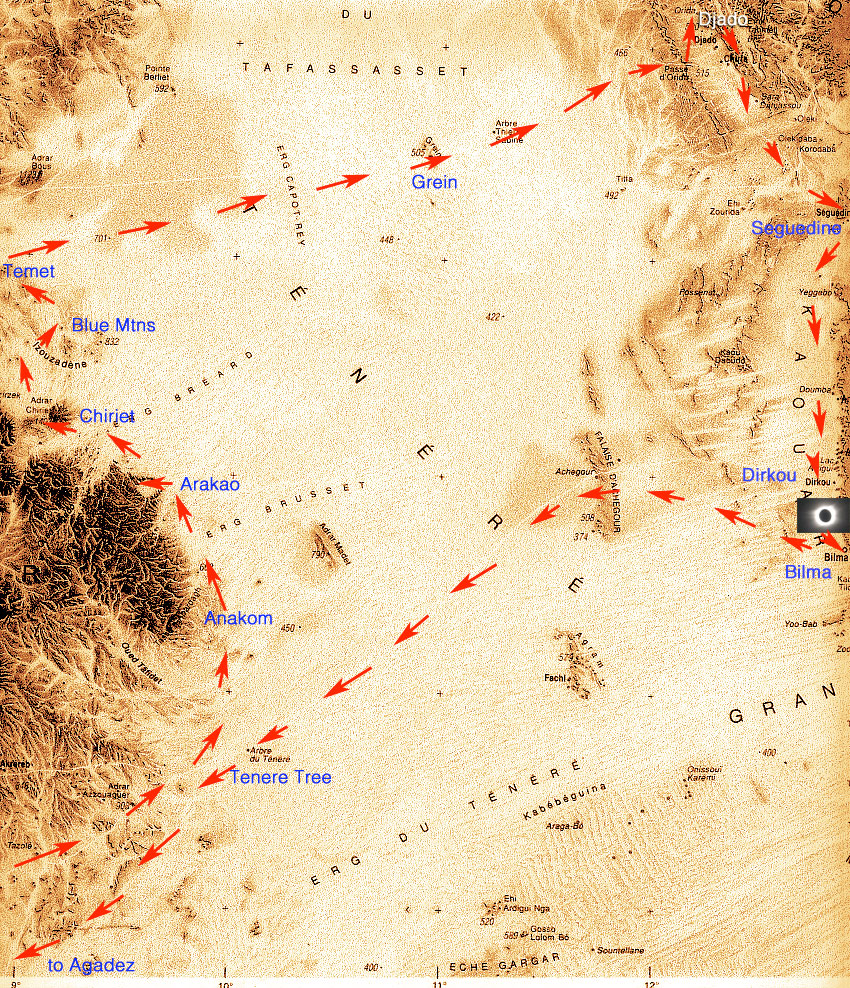

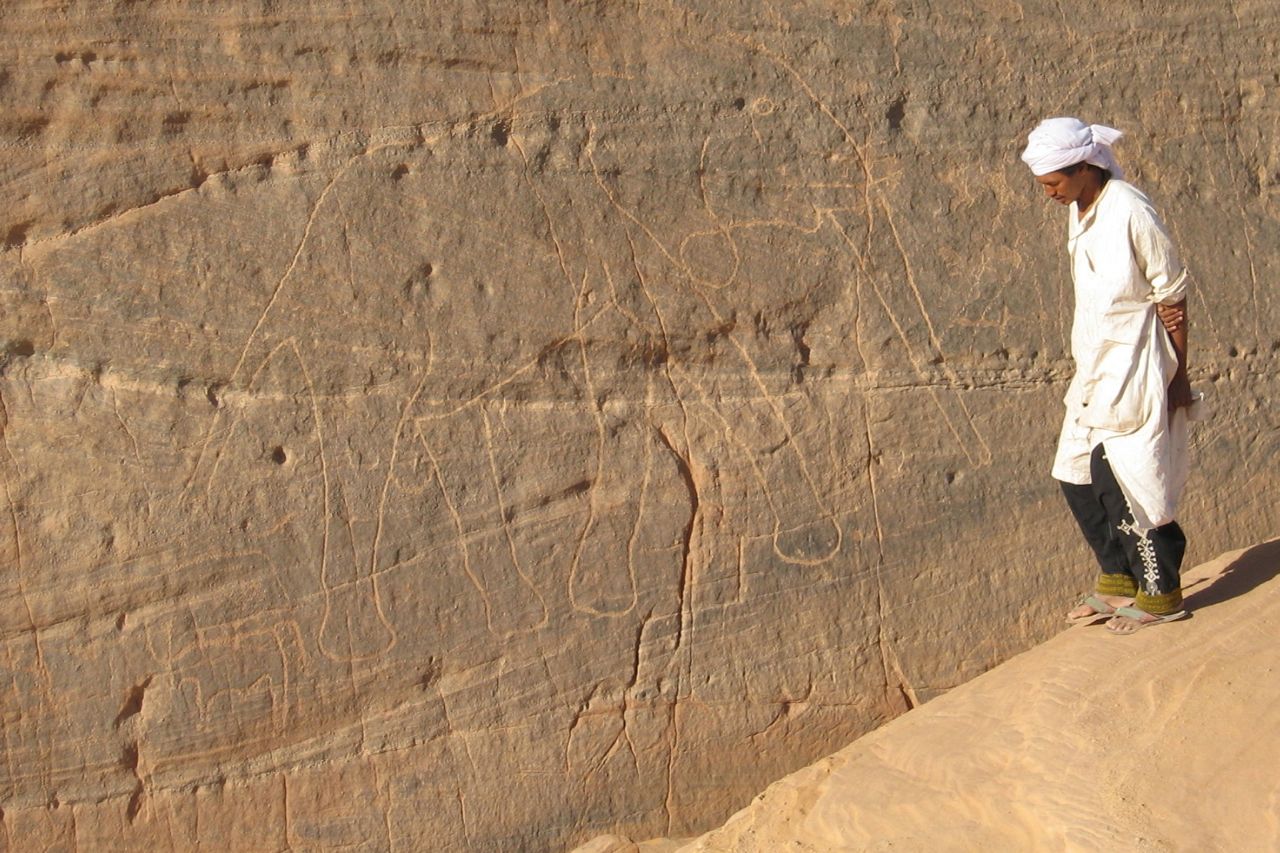

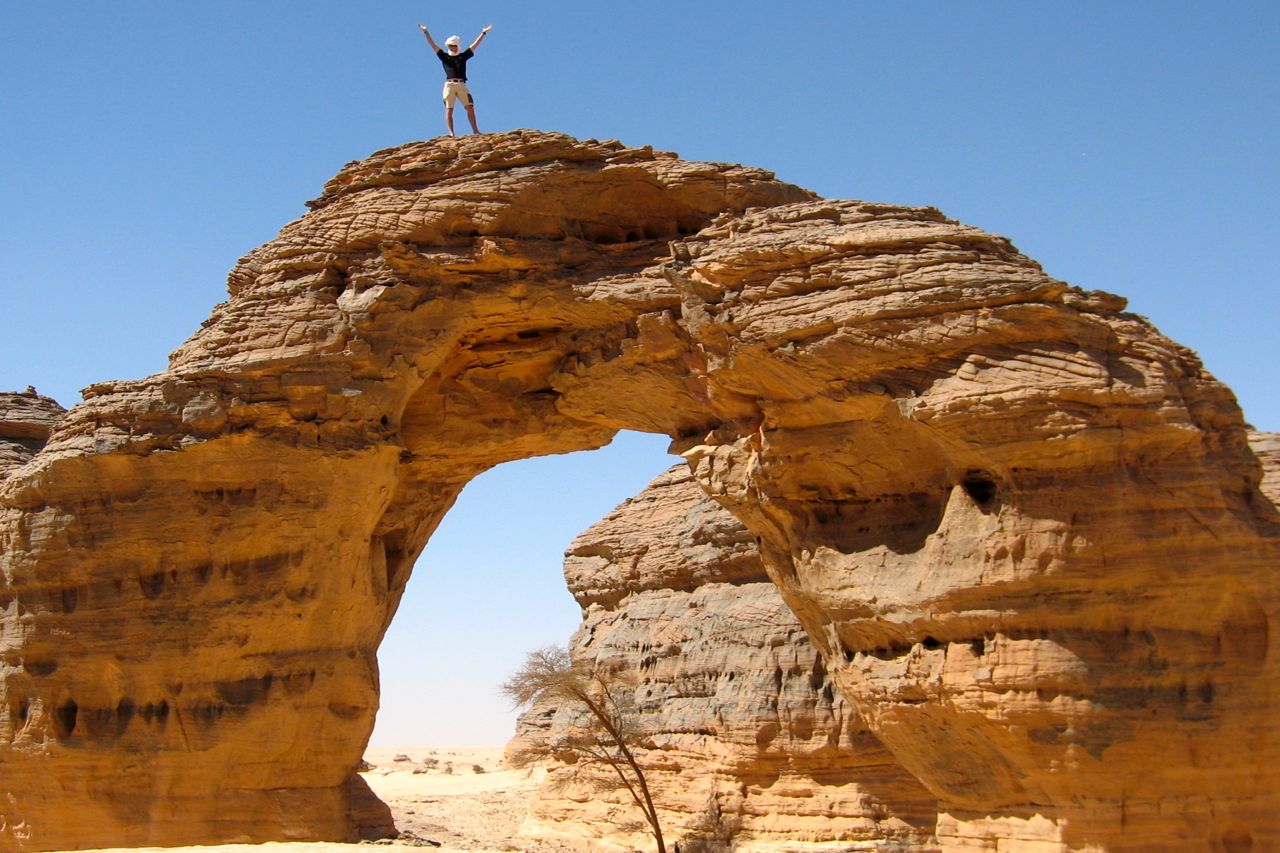

‘Clear skies or your money back’, I crowed confidentially when I pitched my tour. In my mind far better to take it to Niger, where the track of totality passed right between Dirkou and Bilma on the far side of the Tenere circuit. On the way we could take in the classic Tenere Loop (right), one of the best fortnight’s you can spend travelling in the Sahara. It includes the Aïr, Arakao, Adrar Chiriet, Temet dunes, east across the sands to the mysterious ruined citadels of Djado and Orida and the nearby salines of Seguedine and Bilma before heading back through the Bilma Erg and past the Tenere Tree to Agadez.

I secured ‘saharaneclipse.com’ in plenty of time and set up an enigmatic front page (left). Only those who moused over the eclipsed sun found their way to the back pages and further details. And so about eleven of us from seven countries shuffled across the tarmac of Agadez airport, paid the special ‘eclipse tax’, piled into the loaded jeeps and lit out into the Tenere to see what we could see.

Came the day I was nearly forced to eat my ‘Clear skies…’ boast but a great local crew, the international group and not least the fabulous deserts of the Aïr, Tenere and Djado made for one of my most enjoyable and trouble-free Saharan tours.

Looking at the screenshot of the Google sat image on the right (direct link), the village of Arawan some 250km north of Timbuktu seems to resemble the debris of a shipwreck adrift in a caramel swell.

I’ve never been there, though passed some 80km to the northeast during our SEQ transit to Algeria in 2006.

Some might recognise ‘Arawan’ as the rap track from a Tinariwen album, Amassakoul or ‘The Traveller’. As far as I can tell the lyrics match the received assumption of a once great but now near-abandoned town slowly being either swallowed up by the pitiless desert or simply changing times.

Arawan is the only permanently occupied village on the 700-km azalaï caravan route (left) to the salt mines of Taoudenni in the far northwest of Mali. Today, depending on the time of year, a couple of hundred live in Arawan, including an imam who tends to the shrine or mosque of the holy man or saint, Cheikh Sıdi Ahmed ag Ada (or Agadda; 1570-1640). It was he who refounded the settlement in the 17th century and is venerated as the ancestor of all the ahl Arawan (‘ahl’ being to Arabic as ‘kel’ is in Tamachek: ‘people of…’). The ruins of Dar Taleb (or Alphahou), just to the north of the village, have been dated back to the third century AD, making the site much older than Timbuktu.

The basis of any settlement is a reliable water source and Arawan once had scores of wells to enable the speedy watering of the passing caravans. You can only assume that nearly 500 years ago there was more pasture to sustain a livelihood than there is today. As it is, this flat expanse of northern Mali seems to be typified by enigmatic patches of grassy tussocks scattered across entirely barren sand sheets and the very occasional escarpment.

Fast forward from Sıdi Ahmed a few centuries and the Swiss American Ernst Aebi comes to Arawan. He’d made his fortune developing property in New York and had raced the Dakar. In the late 1980s he discovered the semi-derelict Arawan and decided to establish the ‘Arbres pour Araouane’ project to help revive the village.

He helped build a small market garden, a tamarisk plantation and eventually even a small hotel; all typical ‘Aebian’ ventures, which owe more to his dynamism and energy than sustainable, long-term goals. Little remains of the hotel today and the garden was ransacked in the early 90s at which time he was forced to leave the region during a Tuareg rebellion and the vicious army reprisals which followed. He wrote a book, Seasons of Sand, about his time there, and later a film: ‘Barefoot in Timbuktu‘, was made about his return to Arawan, which had of course reverted to the state he’d found it in 20 years earlier.

Now over 70, Aebi (left) does sound like quite a character. Pick on any post from his blog and you’ll get the picture of the guy who is still living full life.

More recently social anthropologist Judith Scheele wrote an interesting paper about a pilgrimage of urban, well-to-do ahl Arawani from Bamako to the shrine of their ancestor, Sıdi Ahmed ag Ada. I don’t read such material by habit, but her digestible account of the complex social interplay of the long departed ahl Arawan and their timely piety set against the poverty-stricken and somewhat cynical villagers is amusingly absorbing. It turns out their trek was not just a spur of the moment adventure. At that time in 2007 oil exploration was underway in the Taoudenni basin to the north, and throughout history the ahl Arawan traditionally had a stake in the control and subsequent revenue from the salt mines. By marching into town, the dilettante ahl Arawani hoped to flag up their credentials for all to see as historically legitimate beneficiaries of the region’s resources.

Her short paper also sheds a light on the complex ethnicity of northern Mali; doubtless no less than any other region of Africa. I’d assumed it as just desert Tuareg or void, but the Tuareg homeland is specifically in the Ifoghas or ‘Adagh’ as some like to call it; northeastern Mali centred around Kidal. To the west of the Tanezrouft piste are the Tilemsi Arabs, Kounta, also Arabs and what might be called ‘Moors‘ around Timbuktu, with Songhai (indigenous West Africans) spread right through.

Setting aside the thorny issue of former slaves of both Arabs and Tuareg, there are added hierarchies based on religious ancestry or legitimacy – those who called themselves sharif or descended from the Prophet. I learned about the similar status of ‘Hassans’ from American PCVs in Mauritania in the late 80s. In this way a penniless nomad in Arawan may claim to be higher up the social scale than an ahl Arawan who’s just driven up from Bamako in a flash Land Cruiser.

Some scoff at the holy man of Arawan. It’s clear from his name that Sıdi Ahmed ag Ada was no more than a Tuareg, probably from Essouk in the Ifoghas (‘ag’ being a Tamachek equivalent of the Arabic ‘bin’).

Essouk, 60km northwest of Kidal, was the site of a Tuareg music festival (above) for some years; Gregg Butensky wrote about it in my Sahara Overland book. Nearby are the pre-medieval ruins of Tadmakka excavated by Sam Nixon Nixon and on a par with the better known former entrepôts of Koumbi Saleh or Aoudaghost in southern Mauritania, or Ouadane (left) further north.

For a good impression of the region north of Arawan here’s a detailed report and gallery from 2007 by Barbara and Henner Papendieck who paid a visit to Taoudenni as part of their humanitarian work in the region (map right, click for full size). This was just before the spate of kidnappings kicked in, but even then they needed to organise an armed military escort.

There are some great images of the actual mine site as well as the old prison. Below is a dramatic picture of the Sidi’s mosque in Arawan.