Part of the Sahara A to Z series

See also:

Mysterious circles

Interesting academic document

Nick Brooks’ photos (Western Sahara)

Archeoland / Sahara loads of images and downloads

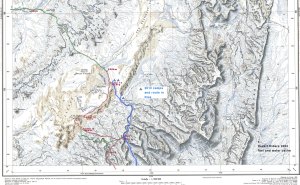

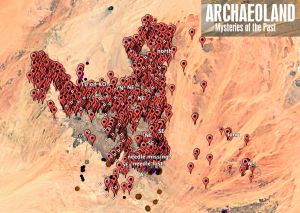

As on previous occasions, the route of our camel trek through the Immidir will rest a day at Aguelmam Rahla, a reliable waterhole at the mouth of the Oued Tafrakrek canyon (blue line on map, left) where the Tissedit plateau drops down to meet a band of dunes. I’d been wanting to make a diversion here since scanning Google Earth a few years back and noticing the innumerable pre-Islamic tombs (‘PIZ’) in the area (below).

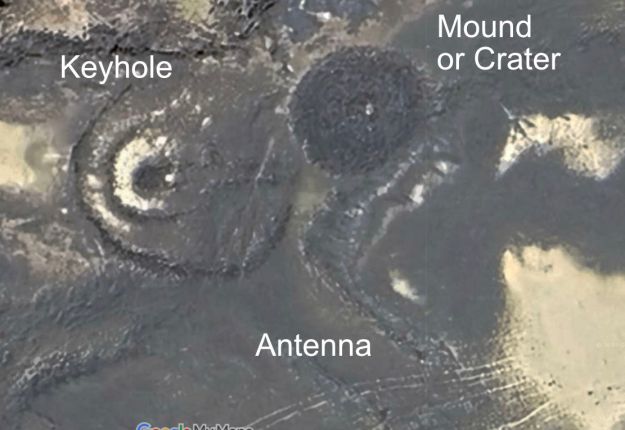

Looking again on Google Earth some time later, less than an hour of nosing around revelled three dozen keyhole, antenna or mound-ring tombs within a few kilometres of the waterhole. I didn’t bother counting the less distinctive mound tombs or just plain tumuli. In fact the proliferation of tombs here isn’t so unusual, given the topographic features already listed: edge of a plateau, former river mouth, band of dunes – all common factors found at former Neolithic occupation sites.

On the first crater tour in 2007 we walked along the base of the dunes, northeast from Aguelmam Rahla, and discovered several grinding stones and other artefacts at the foot of the dunes. And in 2012 one of us came across a near intact pot (left) at the foot of a dune, as well as napping (stone tool chipping) sites. You commonly find ceramic shards or even larger pieces, but I’ve never found an intact pot.

There’s something compulsive about Sahara tomb spotting on Google Maps, searching the featureless desert floor for the clear signs of prehistoric human activity. Once out there it can give a purpose to a journey that’s otherwise just agreeable recreation and adds a hint of treasure hunting.

It reminds you that the Sahara of 6000 years ago was not a desert, but a much less arid savannah. Among others, KenGrok spent years scanning and collating unusual imagery on Google Earth’s layers, including pre-Islamic tombs in the Sahara. In 2019 Google erased his work, but his baton has been picked up by ‘syzygy‘ on Google Earth Community, as well as Manfred Boelke at archaeoland.eu (his image below).

Broadly speaking, half a dozen tombs styles have been identified with clear regional limits as shown above. The most common is simply a mound of stones or tumulus which can be huge and can have a central depression to resemble a volcanic crater. Sometimes the mound may be surrounded by a ring – a mound-ring tomb. All over the Sahara tombs are usually found in clusters; find one and you’ll find others nearby. It suggests an auspicious place for burials or just a former occupation site with an adjacent burial ground.

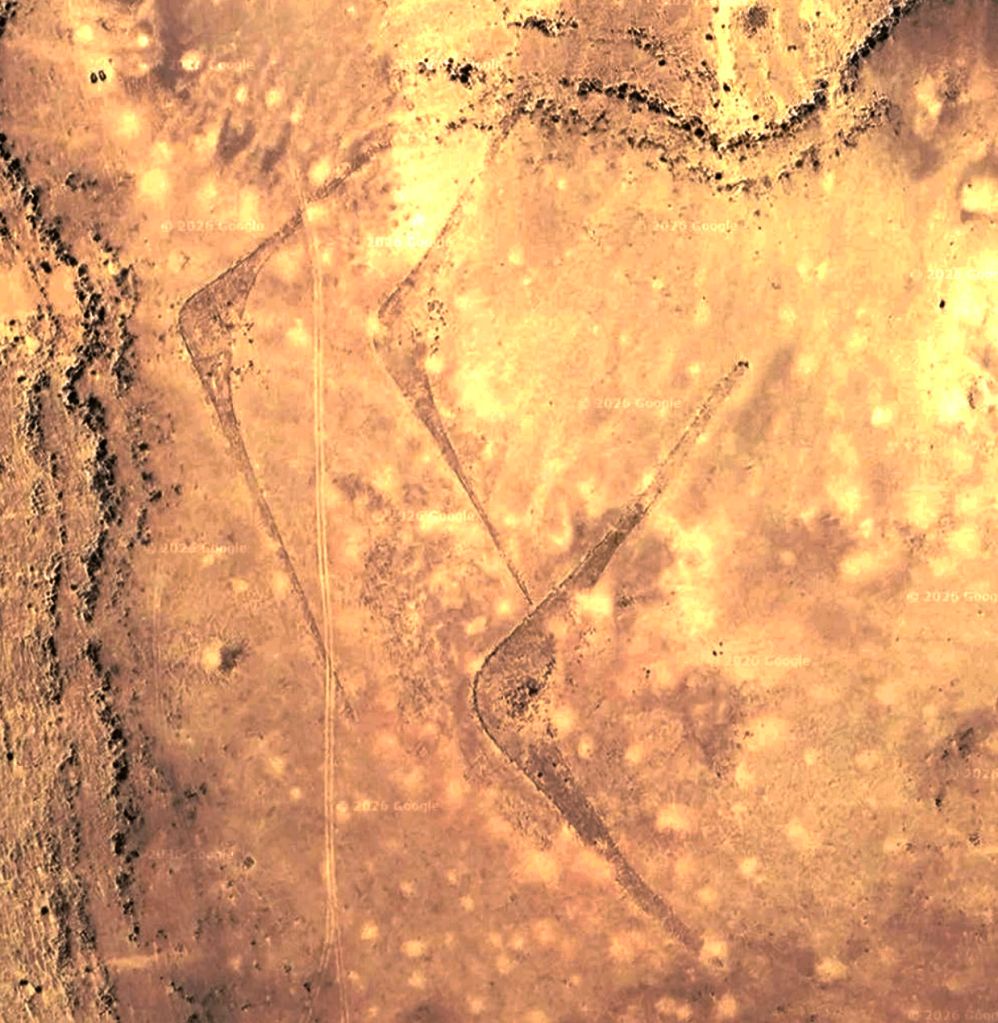

Antenna or crescent tombs have open arms spanning out from a tomb mound apex at around 120° and can be up to 250 metres or more, end to end. They are prolific in southeastern Morocco (bottom left; 27.6971, -10.8665), but are also found in Algeria by the thousand (25.86007, 4.36847). The finest ones have long, slender arms while small ones can be stumpy and even almost simple hemispheres.

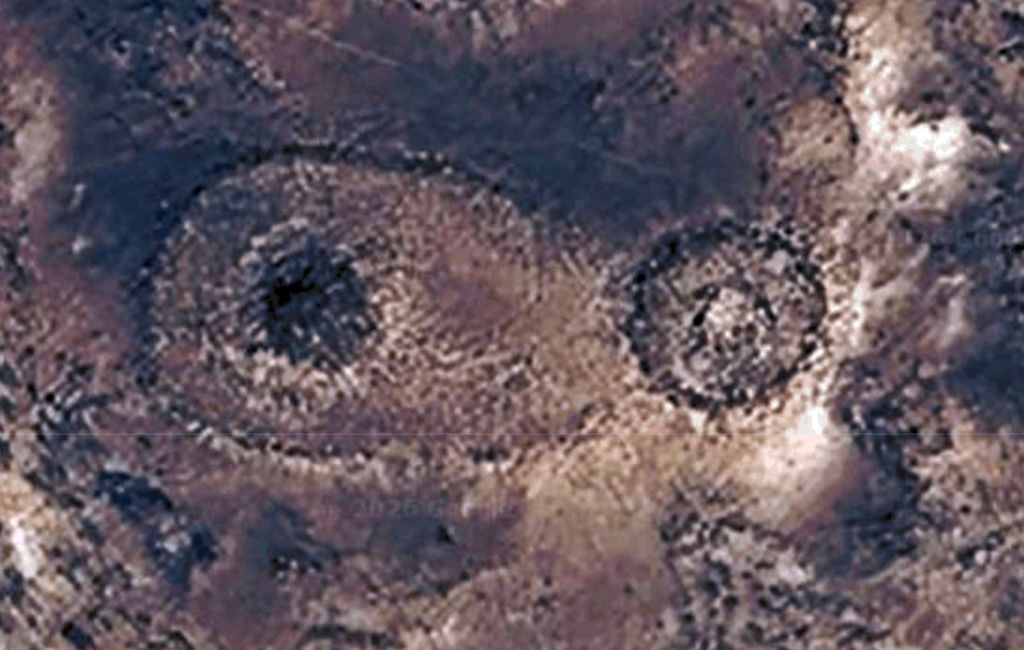

Keyhole tombs are two concentric round or oval rings with the tomb mound near the middle and a corridor leading to the outer ring. Below is a famous keyhole near Djanet at the base of the Tassili n Ajjer plateau where you’ll find them in their hundreds.

A version of the keyhole is called a goulet tomb (below; French for narrow passage, as in ‘gullet’). They have a large perimeter ring with the tomb mound on the ring’s edge and a line or corridot of stones bisecting the circle. I find these much less common.

A version I’ve read about but not seen is called the rather ill-named compass tomb which is found exclusively in the Tibesti massif of northern Chad (left).

In the clearest examples like below, an arm or spike extends from the oval ring to one side, resembling a tadpole, tennis racket or snow show. As always, in the centre of the ring you will see the tomb mound.

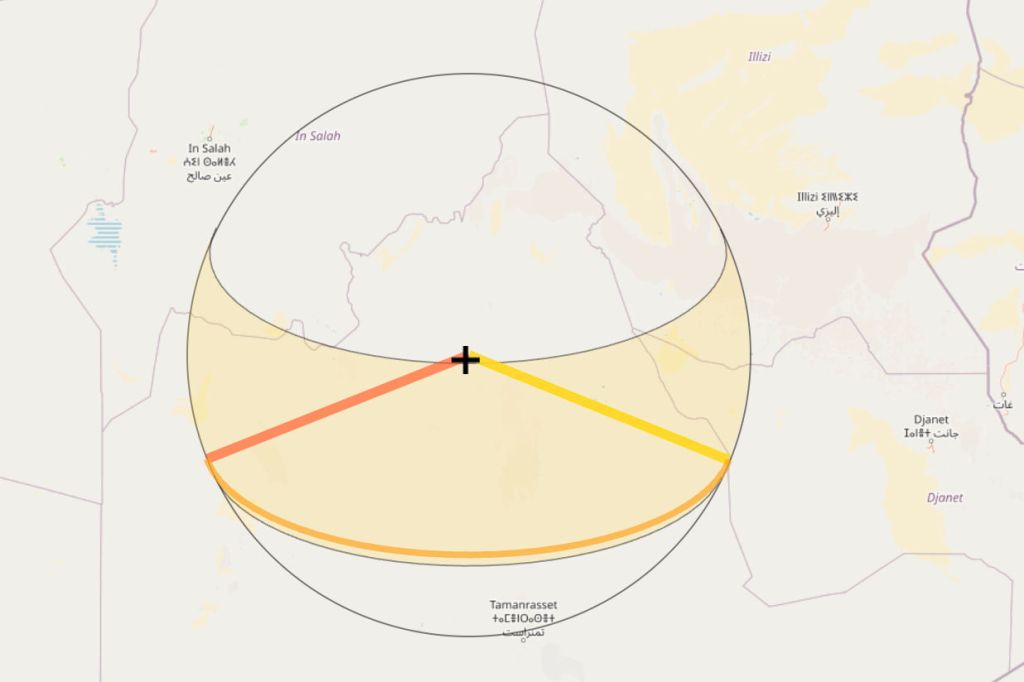

Sunrise orientation

By now you may have spotted a common directional theme among the non purely circular pre-Islamic tombs: they all have elements which point at about 110° which, at these latitudes of around 25°N is towards the rising sun. Just as with many ancient, pre-monotheistic civilisations, the sun was the key element in their cosmology, with ‘the way to rising sun’ suggesting rebirth or afterlife. But just like builders, occasionally they got it wrong, like the compass tomb above right in the sands of the western Tibesti.

There is one final category of tomb which is also commonly foiund in the Sahara. The Islamic tomb. Contemporary Moslem cemeteries on the edge of desert towns are relative plain affairs, cleared rough ground covered in plain head stones. The ornate tombs below are out in the desert, far from the nearest village (Arak, Algeria). Usually the headstone is at the eastern end of the tomb, though of course with Islam that’s related to the direction of Mecca, not sunrise. These tombs, which might be said to have an entrance on the left and an east-pointing mihrab (‘altar’ niche) in the perimeter ring, will be a few hundred years old.

Not all pre-Islamic tombs fit the above categories. Below left, a keyhole shape but with no corridor, overlapped by a mound-ring tomb. Perhaps the corridor stones were reused for the mound-ring. Below right, a mound-ring with a perimeter mound like a goulet – a descendant’s tomb? I read here that excavated tombs in the Oued Draa of southern Morocco were more like mausolea, with a walled crypt under the stone mound where successive generations were interred. I’ve never read of a tomb being excavated like this in the Sahara, though I’m sure it must have been done, by either grave robbers, archeologists or the curious. I remember one time in the exceedingly remote Gilf Kebir, we came across a plain, desolate tomb (rare in that area) on a day-walk. Someone half-heartedly dug it up but found neither bones nor treasure. It didn’t seem like the right thing to do.

Often this fascination and excitement with pre-Islamic tombs falls a little flat on actually finding one on the desert floor. On a 2012 Immidir trip I was excited about finding a huge antenna tomb that lay close our path on Day 6 or so. On Google (above) the massive structure with a span of over 300m looked amazing, but by the time we tracked it down (left), it was too big to appreciate from ground level. My group seemed to say… ‘and the purpose if this diversion was…?’. ‘Flying’ over these tombs on satellite imagery, like Peru’s Nazca lines, is how they’re best appreciated.

How old are these ‘pre-Islamic’ tombs? Well in the central Sahara I’d say the Islamic era began to have an impact a couple of hundred years after the Arab Conquest of North Africa between AD 647–709. I imagine this swept like a tide west along the south Mediterranean coast, down the Atlantic to present-day Mauritania and then ‘eddied’ back west towards places like Timbuktu. Other eddies may have spun off sooner to places like Ghadames in Libya, following trans-Saharan trade routes into the interior.

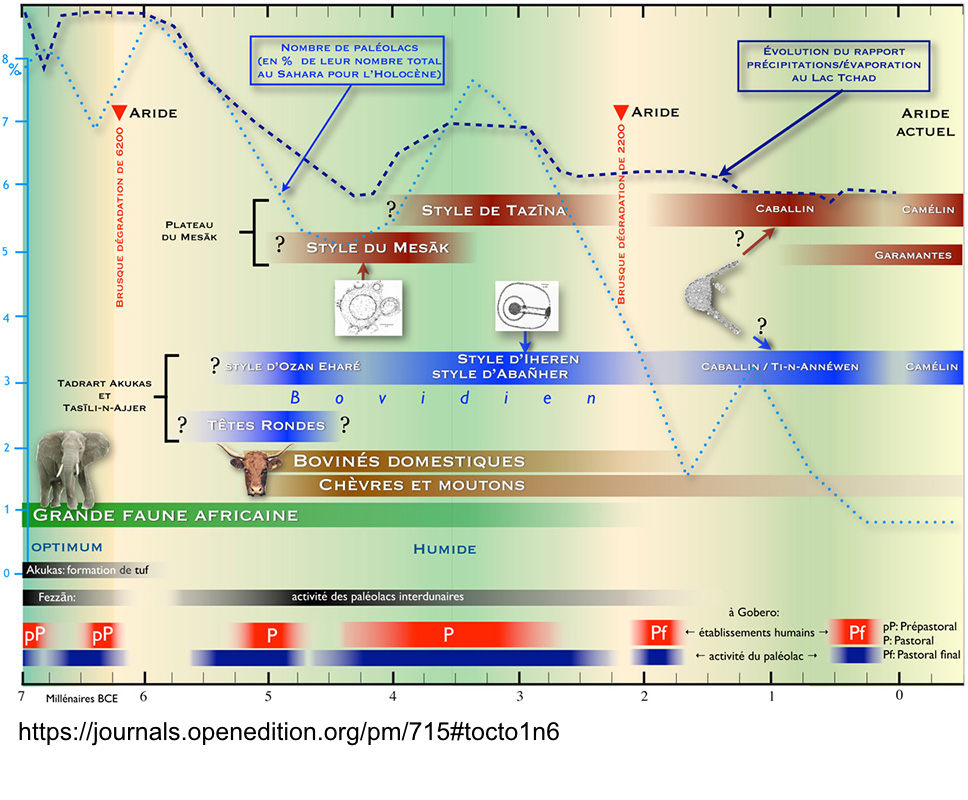

Chances are these tombs, like the huge keyhole on the right in the Immidir (above), are only around 4000 years old, maybe double that. That means they followed the apogee of rock art some 6000 years ago following a climate change (the ‘Humide’ in the image below) which briefly repopulated populated what is now the Sahara. By this time megalithic tombs and temples became widespread across the ancient world, most spectacularly in ancient Egypt and western Europe.

You don’t have to venture into the deep Sahara to see keyhole tombs. In southern Morocco, just a short distance from Erg Chebbi and three miles west of Taouz, on the west side of the Oued Ziz are a cluster of tombs. Like Aguelmam Rahla they’re situated on the edge of a plateau and by a former big river as well as an erg – and not all with entrance ways pointing east.

Below, a curious structure on the Oued Tagant valley midway between Tam and Djanet. And below that, another in the Hoggar, just southeast of Assekrem. I’ve seen these elsewhere in southern Algeria but their meaning is unknown. The guides and old Saharan expeditions just call them ‘tombs’ but they look different and newer than PIZs.

More about them here.